HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_013501 - HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_013795

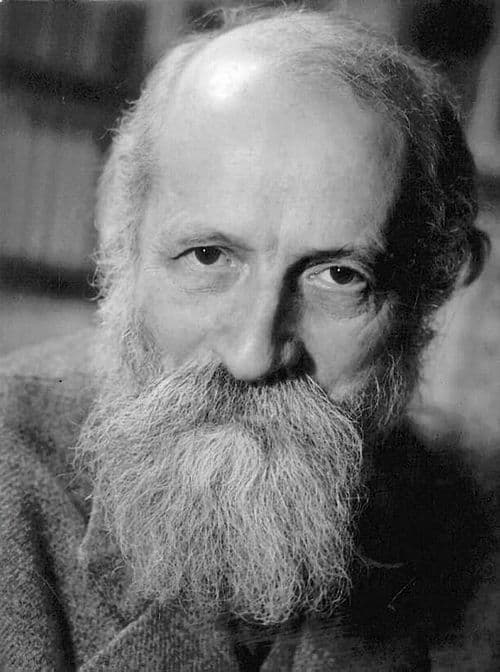

THE NEARNESS OF GRACE

A 295-page manuscript from the House Oversight Committee files, written by Arnold J. Mandell, examining spiritual transformation through the perspective of scientific inquiry.

This document appears to be a manuscript titled "THE NEARNESS OF GRACE: A PERSONAL SCIENCE OF SPIRITUAL TRANSFORMATION" by Arnold J. Mandell. It includes an acknowledgement to the Fetzer Institute for their support and explores themes blending science and spirituality, particularly within the context of personal meaning. The document also references dynamical systems theory and includes a table of contents outlining chapters on topics such as entheogenic entropies, phase transitions, and the relationship between faith and rationality.

Key Highlights

- •Arnold J. Mandell authored this manuscript examining spiritual transformation through scientific frameworks

- •The work received backing from the Fetzer Institute, which focuses on spirituality and science research

- •The manuscript attempts to bridge scientific methodology with questions typically reserved for religious or philosophical inquiry

Frequently Asked Questions

Document Information

Bates Range

HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_013501 - HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_013795

Pages

295

Source

House Oversight Committee

Date

March 22, 2005

Original Filename

Nearness.pdf

File Size

1.34 MB

Document Content

Page 1 - HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_013501

THE NEARNESS OF GRACE A PERSONAL SCIENCE OF SPIRITUAL TRANSFORMATION Arnold J. Mandell HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_013501

Page 2 - HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_013502

Table of Contents Acknowledgement ................ 00. ccc cece cece eee e nce n acces ene e eee eneensenaeenes 3 Chapter 1: In Search of the Miraculous .......................ccccceee eee ene ees 4 Chapter 2: Doesn’t Everybody ............... 0.0... ccc cc cee e cece ee ee ee eneeeenens 22 Chapter 3: Transmogrifications Of Energies .........................cceceeeee 42 Chapter 4: Sensual In-Between Entropies .........................2.eceeeee ees 64 Chapter 5: Some Entheogenic Entropies .........................cceeeee ee ee ee 87 Chapter 6: Pentecostal Phase Transitions ..........................ccseeee eee 122 Chapter 7: Amphetamine Roll-Up And Splitting ..........................008 144 Chapter 8: Faith And Rationality ..............0... 0.0 cccc cece cece eee e eee ee nes 168 Appendix: An Intuitive Guide to the Ideas and Methods of Dynamical Systems for the Life Sciences ............... 186 HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_013502

Page 3 - HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_013503

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Appreciation is expressed to the Fetzer Institute for their support of this work. Particular thanks are due their imaginative Vice President, Dr. Paul Gailey, who shared my vision and hope that these somewhat disparate themes could be blended into a meaningful whole. Time and the reading by others will tell whether this idea was realized. The Fetzer Foundation and Dr. Gailey have facilitated exploration into blends of science and spirituality, particularly in the context of personal meaning. They also have a history of supporting serious work in this era’s most powerful and rigorous exercise in holism as represented by the mathematical and applied mathematical fields of modern dynamical systems theory. Fetzer very special environment and years of dedication have encouraged the variety of personal meanings within science to emerge and be recognized as legitimate and important parts of the research enterprise. It would be difficult to imagine a more propitious context for this effort. The book is dedicated to my daughter Buna, and to my intellectual and creative companion, Dr. Karen Selz, whose deep and lovely mind wrote much more of this book than is formally acknowledged. HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_013503

Sponsored

Page 4 - HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_013504

CHAPTER 1: IN SEARCH OF THE MIRACULOUS More than a half-century of naive persistence and driven search for unity in the biophysics of mind and personal spirituality as the basis for healing transformation has led me into many laboratories. The motivation may have been genetic. My father said that we were descended from several generations of Jewish mystics, none of them able to attain the salaried status of rabbi or cantor. These ecstatic men lived lives of peripatetic eccentricity, stirring congregations with provocative insights and uncomfortably personal inquiry. But only for a little while. Soon they were asked to leave the synagogue and often their Eastern European Jewish townships called shtetels as well. My father, in the first generation of our family without rabbis in over a Century, was a businessman-musician, who in the early mornings studied Talmudic commentaries. He taught me about why it was that most interpretations of the book by the rational, physician, lawyer, philosopher, Moses Maimonides, called Guide for the Perplexed, were in error in their assumption that man cannot understand God’s nature with his mind. He took issue with the opinion that the union of a person’s intellect and Spirit with Him was not possible as long as a person was living. Ibn Tibbon, Maimonides’ best-known early translator and interpreter, relegated the cognitive, analytical, physical and alchemical transformational sciences to the earthly, not spiritual realm. My father disagreed. He espoused the work of the 13" HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_013504

Page 5 - HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_013505

Century proponent of a school of Jewish ecstatic mysticism, Abraham Abulafia, whose interpretation of the Guide and his own Commentary on the Secrets taught that the human mind, if transformed into a “state of active intellect,” could become one with Spirit, realizing the Kingdom of God in rational mystical experience in a state of excitement with new ideas. The new consciousness achieves deep knowledge of both the “upper” and “lower” realms of what he called “reality” both spontaneously and directly. He said that without personal transformation, this knowing is not possible. Abulafia’s lesson was that the mundane intellect of man has the potential for transformation into another kind of mind in a spiritualization of thought. This occurs via developmental stages that begin with intellect and imagination and culminate in what he called prophetic emanations. The exercises leading to this transformation are to be strongly willed and practiced with regularity. This work results in ascension to an ecstatic state accompanied by great intuitive powers, which Abulafia called “prophesy.” Ibn Adret, the Chief Rabbi of Spain at the end of the Thirteenth Century, banished Abulafia from the Country, a Century before the Spanish Inquisition ousted all the Jews. Following what my father said was required in the practice of Kabbalah, a 13" Century tradition of esoteric and mystical interpretations of the Scriptures, | learned the secret meanings of each of the twenty-two letter Hebrew alphabet. Much like the Platonic view of mathematics, that it existed before the physical universe, these symbolic equivalences were believed to be eternal in the transcendental realm. One of the rare written accounts of this oral tradition is in the thirteenth-century Hebrew Book of Splendor called the Zohar which describes the Hebrew alphabet as the heavenly code of the cosmos. | learned that the Tegragrammaton’s repeated letter Hei, being fifth in the Hebrew alphabet, represents the number five. In the Kabbalistic tradition, He/ implicates the functional five-partition of the human inner self or soul. The five parts are: nefesh, instinctual drives; ruach, mood, affect and emotions; neshamah, cognitive activities of the mind; chayah, efforts to understand and _ attain transcendence; yechidah, experiencing the world as a cosmic unity. Later in life as HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_013505

Page 6 - HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_013506

a psychoanalytical neuroscientist with a computational bent, the partitions divided thoughtful, forewarning forebrain from automatic and stereotyped hind brain, the signal analyzing thalamocortical system from the emotional and impulsive brain stem-limbic, the symbolically logical left from _ intuitively geometric right hemispheres. We divide the neurotransmitter moods of dopamine aggression from the transcendentally erotic serotonin and the organized dynamical states of periodicity and quasi(multi)periodicity from the real world complexity of chaos. | learned that it is comforting to divide an unknown whole into two or more unknowable parts. The Jewish guru and Hebraic tutor of my childhood, Rabbi Isadore Kliegfeld, smiled when | told him about my sudden loss of panic during nighttime Hebrew letter meditations. He said that | had had received personal evidence that these powerful symbols could call forth the transformational powers of God. He said that | had been given a blessing, in Yiddish, a nachas. Maybe panic is not that far from the transcendence of an activated mind. In my tenth summer, behind closed door in a hot back bedroom, first by accidental touch and then by more systematic chaffing, | evoked a pleasurably urgent and yawning feeling that began in the lower part of my abdomen and back. It filled me with thought emptying fullness that a sudden involuntary burst of pelvic contractions found resolution in an hour or two of an unexplainable sadness. | had been struggling to understand my father’s well warn copy of William James’s Varieties of Religious Experience and | wondered if | had been visited by one of the altered states he described. Was this what he meant by a _ transformative experience? A few months later, a late night meditation produced physical evidence, a thick, sticky, salty sweet stuff that by morning stuck my sheets together. Later that year, in my father’s library, | found a translation of the 1500 BCE Egyptian Book of the Dead. It contained a creation myth of two Gods in which “rubbing with my fist, my heart came into my mouth and | spat forth Shu and Tefnut.” Psalm 23, read rather regularly in Sunday school, began to make me wonder about the meanings of*...rod and staff that comforts...” and what was meant by “...my cup runneth over.” Among the ten regions of the Zohar, connecting the inner world of HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_013506

Sponsored

Page 7 - HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_013507

man to the upper world, is the tree of ten sefirot in which Yesod , the phallus, occupies a central place. Now we’re allowed to know that G-spot stimulation of the para-urethral glands in the female can result in spurt as well as a cup that runneth over. Other occasions of the temporal disappearance of the self-conscious | occurred while doing the theorem and proof work of high school geometry. Axioms and the rule bound processes of deduction created difficult journeys from that which was given to what should be found. Rocking back and forth in a desk chair for hours, chewing on fingernails, cuticles and pencil ends, time disappeared in a none self aware state of work-a-day well-being. Sri Aurobindo’s Bhagadvad Gita described this state as one of the rewards of karma yoga. Abulafia’s Kabalistic School emphasized the importance of hitbodedut, detachment and seclusion in concentrated thought, as a technique for the attainment of spiritual “intensification.” Stacks of lined yellow paper piled up full of blind alleys as | lived in humbling dumbness. One of my teachers of mathematics described it as the working mathematician’s dark night of the soul. A breakthrough to a route from premises to proof brought an expansive rush. Engagement in a struggle to fuse two differing contextual worlds may be transporting. Geometric visions can be used to do imageless algebra in a brain state that feels like intuition. The brain does something like this: Let the number of a sequence of unit squares, each side of measuring 0 to 1, be the denominator of a series of fractions, say fifths. Now put five of these boxes in a row. Then the sequence of all possible fifths, 0/5,1/5, 2/5,..5/5, is inscribed by cutting the vertical sides of the five sequential squares with a diagonal from the lower left of the first one to the upper right corner of the last. This line cuts each sequential square’s front boundary with vertical lengths, 0.0, 0.2, 0.4...1.0 in a series of decimal fractions equivalent to the sequence of all possible fifths, the proper fractions 1/5, 2/5...5/5. It was Abulafia’s kabalistic belief that symbolic, (algebraic), operations in (geometric) spaces can unify the “upper” and “lower” worlds in the eternal tensions between the body and soul, the inner world and the cosmos, the conflict making the global system both sensitive and stable. The geometric-topological approach to HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_013507

Page 8 - HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_013508

modern dynamical system’s theory describes a convolution of the expansive motions (as in the upper world) and contractive motions (as in the lower world) embedded naturally in the curved time and space geometries of what are called hyperbolic spaces. Each point in this space can be visualized as a little saddle in which orbital flows from pommel and back flow down to the seat, bringing points together in contracting motion, and flows away from seat down along the sides are expanding the distance between nearby points.. In the middle of the saddle, simultaneously expansive and contracting orbits demonstrate hyperbolic stability composed of intersecting destabilizing and stabilizing influences. Loss of this countervailing hyperbolic dynamical stability results in global system transformations called bifurcations and/or phase transitions. Transformation as a loss of stability is a theme of a recent poetic translation of portions of the Zohar called Dreams of Being Eaten Alive by David Rosenberg. He writes that at some time in the difficult journey through the often- incomprehensible Zohar, in order to gain entrance to the kabalistic cosmos, there arose what he called “heartbreak.” “No matter how much intellectual study is involved, the reader cannot understand the text unless he or she has offered his heart to be broken on the altar of poetry...and prayer.” Surrender may be the source of the strange, uplifting feeling of worked through dumbness. My mother, once a conservatory teaching assistant in piano, sat beside me while | practiced almost daily, weekends included, from the age of two until the midteens. Her quiet analytic counter-point sounded mathematical, “You can hear that that this harmonic progression goes through intervals of fourths of dominant seventh chords.” | felt the persistent lack of harmonic resolution as growing tension in my groin. “If you transform each of the 12 notes in a chromatic scale, multiplying it by five (in what mathematicians call) mod 712 (the numbering system goes from one to twelve, not ten, before it repeats), one can recover the circle of fourths, the commonest harmonic chord progression in music.” Though her computational talk supported rational thought, in my adolescent heat, the addition of Charley Parker’s flatted fifth and ninth to the dominant seventh chord led suddenly somewhere else and she knew it. Hearing my arrangement of a Beethoven piano piece become a HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_013508

Page 9 - HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_013509

mix of classical and modern jazz themes that | called “How High the Moonlight Sonata,” she laughed lasciviously as though tickled by this sensual violation of musical canon. A boogie-woogie Bach two and three-part invention brought more excited disapproval. Mysterious are the conditions of attentive (preoccupied) and none attentive, (fugued out) disappearing time. | found a musical way for it to happen when improvising: continue to shuffle a small set of notes that stay within the melodic field of the tonal center of an unchanging tonic chord. In contrast, most melodies and their chords leave the tonal center to which they return in harmonic and melodic progression. We can call these conventional tonal centers unstable fixed points. They are attractive repellers of melodic and harmonic expectation. It has been mathematically proven that these hyperbolic systems are globally stable. In contrast, a melody that remains stuck in the tonic chord, a purely contracting stable fixed point, is technically a chant. Paradoxically, it can be shown that this kind of fixed point is globally unstable. Rigid things can more easily fracture. The rich, altered states of consciousness that emerge while hearing the beat of Tibetan monks meditating, the Sufi chant-dances of Rumi and the John Coltrane and McCoy Tyner’s endless, single chord, tenor/piano dialogues exemplify the bifurcation to hallucinatory new stuff arising spontaneously from the experience of unchanging repetition. Constant repetition of the conditioned (expected) stimulus drove Pavlov’s dogs, especially those with “nervous temperaments,” into frozen, catatonic states. Abulafia’s 1280 book on ecstatic techniques, Hayyei Ha’Olam HaBa, recommended the recitative rearranging of a finite set of Hebrew letters, frontward and backward, many times, using prayer melodies, until “...the heart will suddenly become aware of the intellectual, divine and prophetic...” and hitbodedut will rest upon him. The instructions were “...combine letters (and associated musical notes)... reversing and rolling them around rapidly until one’s heart begins to feel warm.” It was in my freshman year at Stanford University when | met Michael Murphy, later to co-found Esalon, the California center for mystical pursuits and naked mud bathing. He is the author of Golf in the Magic Kingdom and with George HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_013509

Sponsored

Page 10 - HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_013510

Leonard, Integral Transformative Practice. | watched him go through a dramatic personal transformation after participating in Professor of Asian Studies, Frederick Spiegelberg’s seminar (with meditation lab) about Sri Arubindo’s interpretation of the Hindu Bible, the Bhagavad-Gita. Shortly after the semester, he climbed into an abandoned tower on campus to continue his meditation. He remained there for several months, refusing to come down even after the Stanford Student Health Service sent a medical school psychiatrist to investigate. | was more than curious about how it was that this hard drinking, and like his brother Dennis, all night poker playing, Phi Gamma Delta party boy, had suddenly become a transcendent ascetic. My girl friend Mary and | signed up for Spiegelberg’s seminar in Indian Religions. We were made breathless by his accounts of administering a Rorschach Test to the Indian Saint, Swami Sivananda. He recounted discussions about God with the artists Paul Klee and Max Ernst and the philosophers Rudolph Otto, Paul Tillich, Martin Heidegger and Martin Buber. As homework, Mary and | practiced breathing awareness mediation twice a day. During the year, Spiegelberg sponsored a visit by the aging but still very lively Aldous Huxley to our seminar. He also brought us Alan Watts and several lecturers from the Jung Institute of San Francisco. Shortly after hearing Huxley talk about the spiritual power of a particular exercise of will and loving thoughts, Mary and | began the daily practice of karessa, some Call it coitus reservatus. | was eighteen and she was nineteen. We found that withholding an orgasm in order to achieve nirvanic extinction of all desires and passions was difficult. We spent hours in karessa meditation, trying to experience the detachment described in the Bhagadvad Gita. This biblical explication of karma yoga told how it was that the warrior, Ardjuna, instructed by God Krishna in the form of his charioteer, was able to detach sufficiently to do his assigned job of killing without emotional involvement. Ken Wilbur, a modern, self proclaimed pandit, an academically oriented articulator and intellectual justifier of the dharma, the spiritual work of Hindu and Buddhist practice, contrasts the nirvana (literally “end”) composed of emptiness in time and space, dharma Kaya in which “...no objects are n arising...” with the lesson of the Bhagavad-Gita. Its message involved realizing 10 HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_013510

Page 11 - HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_013511

ones spiritual unfolding within the stream of real time and space, finding emptiness in the world of form and inaction in the world of action. We worked at karessa so ardently that there was barely enough time left to do our assignments in biology and chemistry. In a darkened room, Mary and | lay legs locked, lying on our sides, moving slowly and rhythmically, humming Om and waiting for our ascension. We worked at making the journey through Sri Aurobindo’s soul planes of higher mind, illumined mind, infinitive mind, over mind and finally, the supermind of infinitely empty no mind. This somewhat unusual way to study for a three credit course in Asian Studies at Stanford grew naturally out of the central message of Spiegelberg’s seminar that whereas “...deriving a universal theology is not possible, having the universal experience is required for an understanding of any of the world’s theologies.” The controversial Bishop of the Episcopal Diocese of Newark who teaches that Christian forms continue to evolve, John Shelby Spong, D.D. says, “...every biblical word represents an attempt on the part of our ancestors in faith to make sense out of a God experience in their time and place. The experience ...is eternal and real. The explanations will never be eternal and real. They will last only as long as the (cultural) mind-set that created them.” Mary got an A+ grade, topping Spiegelberg’s class with a final examination essay, which, in literary detail, described her episodes of samadhi, yoga’s state of unity with the creator. Her 25 page blue book contained accounts of walking fugues, spontaneously strong genital sensations, changes in tastes and smells, sudden feelings of rising spinal-abdominal kundalini, middle of the night dreams of oceanic orgasmic fusion with God. She failed to mention that she was describing her usual pre-menstrual state. During these college years, | learned about two Isaac Newtons The first | met at elementary physics lectures; the unit was about how things worked called mechanics. Logically and computationally consistent but taken on faith, | learned about an invisible field force between masses called gravity that decayed in strength like the inverse of the square of their distances apart and operated in my intuitive world like an electromagnetic spirit. Less occult were the expressions of gravitational fields as contact forces, computed for the tension in the string of a HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_013511

Page 12 - HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_013512

pendulum or the pressure of the floor on a weight resting upon it. Faith in this realm came from exercises in physical object visualization followed by manipulation of self-consistent algebraic symbols. | learned about experiments attesting to the “reality” of these ghostly fields (that now include electric, magnetic and strong and weak nuclear forces), and yet it was the physicists that already believed them who designed the machines to demonstrate them. It was Gregory Bateson, Margaret Mead’s houseboy, lover, photographer and social anthropologist who said, “Newton didn’t discover gravity, he invented it.” One college summer | found a second Isaac Newton, perhaps not so estranged from the first. He appeared in the form of a marble bust in the chapel of Trinity College at Cambridge University, holding the prism he had used to explore the polychromatic properties of light like a talisman. In his essay called Newton, the Man, the early 20" Century Cambridge Don and economic theorist, John Maynard Keynes, said that the Newton of the chapel followed “...certain mystic clues which God had laid about the world to allow a sort of philosopher’s treasure hunt to the esoteric brotherhood.” Michael White’s biography, called Newton the Last Sorcerer, described his work as an attempt to integrate the magic of the Old World with the science of the New Age. Newton’s awe over what he saw as the wonders of the universe maintained him in private theological study throughout his life. Arthur Waite’s Alchemists Through the Ages describes how Newton’s alchemical orientation toward the earth’s fundamental substances such as fire, air, wind and water, their powers and potential for transformation, was joined imperceptibly with his metaphysics and physics. In his hands, experimental observations involving gravitation, celestial mechanics and optics, though motivated by esoteric alchemical theories, generated experimentally accessible phenomena and testable ideas. The French mathematician, Jacque Hadamard, in his The Psychology of Invention in the Mathematical Field, said that mystical preoccupations were never far from the minds of most of the English and European mathematicians and physicists of the 18" and 19" Centuries. This orientation served as an impetus for them to pay attention to the almost imperceptible whispers of their emergent thoughts. E.T. Bell, the historian of mathematics and mathematicians said even 12 HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_013512

Sponsored

Page 13 - HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_013513

Descartes, the essential Enlightenment rationalist, was responsive to his “...call of the Spirit...” Napier the inventor of logarithms wrote an exegetical commentary on the Book of Revelations. The mathematician and physicist, Pascal, believing that contact with a religious relic had cured his terminally ill sister, wrote long tracks about whether or not the Devil could work miracles. The great mathematician, Cauchy, was known for his persistent efforts to convert fellow mathematicians to Roman Catholicism. Gauss, who was not particularly religious, said that a difficult to prove theorem did not result from hard work but “...the grace of God.” In letters between Liebniz, who along with Newton was the inventor of calculus, and a member of the family of great mathematicians, John Bernoulli, used scriptural quotations and biblical diagrams as part of their theoretical correspondence. Perhaps the greatest mathematician of the 18" Century (or ever), Euler, in his Letters to a German Princess, discussed the functional characteristics of spirits and tt the connections between body and soul. Bell said Euler “...never discarded a particle of his Calvinist faith.” It was to the working out of a law of mechanics called “the principle of least action” that Ernst Mach attributed the beginning of the separation of physical mechanics from formal theology. The flavor of this change is captured in his 1893 The Science of Mechanics that stimulated Bridgeman’s 1936 more formal philosophical analyses of physical theory, from a position that came to be called operationalism: the restriction of physical concepts to those definable in terms of the experimental operations required to demonstrate or prove them. Mach said that these events marked the move of formal metaphysical thinking about mechanics and the physical sciences more generally into the personal and private realm of belief and meaning. Maupertuis, an eccentric friend of Frederick the Great and president of the Berlin Academy, proposed the principle of least action as evidence of the infinite wisdom of the Creator. As an early psychopharmacologist, Maupertuis recommended the use of opium to facilitate creative thought and was famously parodied for doing so by Voltaire in his 1752 story in which he is portrayed as the naively foolish Dr. Akakia. The physical law of least action belongs to a set of ideas HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_013513

Page 14 - HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_013514

that are called variational analysis. They involve the natural (or miraculous) selection of maxima or minima in quantifiable physical processes. Of all possible two-dimensional shapes with the same perimeter, the circle contains the greatest area; in three dimensions, it’s the sphere. In his Principia, Newton reports his work determining the optimal shape of round solids, with circles of revolution having the same effective cross section, in order to minimize frictional resistance to gravity in a medium. The principle of least action says that imparting energy; say by a kick, to a physical body on a rigid two-dimensional surface like the earth, results in it taking the shortest route possible from its initial to final position. The related 1650 Fermat’s “principle of least time” is about light. As Feynman explains in his Lectures in Physics, “...out of all possible paths that light might take from one point another, light takes the path that requires the shortest time.” Feynman, using elementary relations from high school geometry, proved that the /east time principle could lead directly to Snell’s law of the refraction of light at the interface of two different conducting media such as air and water. His analogy was the optimal choice of the path to take in order to rescue a pretty girl drowning in the ocean. Whereas the shortest distance to the girl leads directly into the water, faster running along the beach to the point that minimizes the distance required for the intrinsically slower rate of swimming increases the distance traveled but reduces the time required to reach her. Euler attributed the optimization principle to an expression of the meaning and purpose of a loving God. Infused with this spirit, he developed mathematical methods describing smooth variations in position of an object in motion, the Euler differential equation, in which differential coefficients are varied to prove the principle of least action for mechanical motion. He gave the law Maupertuis’s name. Mach quoted Euler’s conclusion, “As the construction of the universe is the most perfect possible, being the handiwork of an all-wise Maker, nothing can be met with in the world in which some maximal or minimal property is not displayed.” Such faith based mathematical formalisms were rejected by Joseph Lagrange, an early 19" Century mathematician, who, among many other things, proved that every natural HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_013514

Page 15 - HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_013515

number could be expressed as the sum of at most four squared numbers. It was his strongly held opinion that metaphysical speculation was both foreign and inimical to the conduct of mathematics and science. His work in the ca/culus of variations led to the development of a system of algebraic manipulations seeking the value of constants, Lagrange multipliers, in place of solving Euler’s differential equations. It makes it possible to immediately write down a computable expression for the maximum of a mathematical equation. The technique is now routinely taught to high school students and with no mention of the role of belief in the perfection of God in its discovery. | was a fortunate freshman medical student. After a visit to his office and a stimulating discussion about some of the correspondences between the ideas of psychoanalysis and neurobiology, Robert Heath, Tulane Medical School’s Gary Cooper-like charismatic chairman of the psychiatry department, offered me a place in his animal and human neurophysiological laboratory. Between classes, evenings and weekends, | used a Horsely-Clarke apparatus, one of the world’s first stereotaxic devices. It allowed the precise placement of electrodes into functionally specific regions of a cat’s brain. The electrodes were cemented to the skull in place and their wires connected to a device by which the frequency, amplitude and wave shape of the electrical stimulation could be oscilloscopically monitored and electronically controlled as the conscious cat walked around the room. | spent hours observing and recording changes in spontaneous behavior that followed activation of various nuclei in the cat’s brain with small electrical currents. Deep in the part of brain that resides in the upper neck, called the lower brain stem, the region thought to regulate functions such as breathing, heart rate, blood pressure, gastrointestinal motility and global states of consciousness such as wakefulness and sleep, | found stimulus sites that, after 15 seconds of electrical activation, led to several minutes of hissing and objectless rage. One cat attacked an empty chair. These regions when activated also inhibited spinal reflexes such as HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_013515

Sponsored

Page 16 - HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_013516

the knee jerk of the standard neurological examination. Such phenomena were already well known in the late 1930’s in what W.R. Hess and later John Flynn, following electrical stimulation of cats in the lateral hypothalamus, called “hypothalamic rage.” In the late 1940’s and 1950’s, work by National Institutes of Mental Health’s Paul MacLean attributed it to the actions of parts of the emotional “limbic” brain, particularly the fear-rage-attack coloring of experience by the temporal lobe’s amygdaloid nucleus. Modern imaging studies in man have shown that this source of emotional coloring is activated by new information, even before the more rational parts of the neocortical brain processes it. How we feel about something new arises before what we think about it. These survival-oriented states of fight or flight are known to be biologically universal and demonstrable in even single cell organisms. A greater contribution to my brain metaphysics followed observations that after several seconds of stimulation of other brain stem sites, the cats became alert but quiet, staring into space for several minutes. Then, they circled slowly and curled up on the ground. This was followed by several minutes of grooming and loud purring. Difficult to handle cats became transiently tame, some coming close for petting. | found that these same sites also increased the amplitude and reduced the threshold for the cat’s knee jerk reflex. Responsiveness increased with calmness. Particularly interesting was the finding that electrical induction of this purring state could immediately stop on-going stimulation-induced episodes of hissing rage. | referred to these experiments with my friends as my neurophysiological studies of Old Testament vengeance and New Testament forgiveness. It seemed that the hissing rage would produce eye for an eye and a tooth for a tooth hypertension, the talon principle of the Old Testament and Koran. New Testament forgiveness would yield low blood pressure health and Jesus was a healer. It was about this time in the early 1950’s that Northwestern University social psychologist, Jim Olds, found that rats could be trained to push levers to obtain current delivery via electrodes in various parts of their brains. Shortly after, Joseph Brady, then of the Walter Reed Army Institute of Research, showed that squirrel monkeys would do the same. With depth electrodes attached to wires running to a HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_013516

Page 17 - HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_013517

miniaturized electronics box strapped to their belts, some of Robert Heath’s schizophrenic patients spent hours pressing their switches with beatifically expectant smiles. It was after several months of cat experiments that Professor Heath suggested that we spend some time interviewing a hospitalized, chronically ill female patient, Donna, before and during the time she was being studied with recording and stimulating depth electrodes in the human _ neurophysiology laboratory. Donna, bony thin in a lose fitting green hospital gown and sandals, had dark red toenails, blonde hair and eyes shadowed darkly. In her mid-thirties, she had never married and, when she could, worked as a beautician. She told us that since her menarche at 13, she increasingly often had episodes of spontaneous ecstatic rushes along with sudden visions of strong white light. She attributed these experiences to visitations of “...an unseen Christ.” She showed me a stack of notebooks filled with hand written accounts of her religious experiences interspersed with biblical quotations and difficult to follow discussions of what she called the Christian ideals underlying the Civil War. She read parts of it to us. One of her memorable stories was about being invited to a Children’s Crusade that had begun in Georgia, led by a great grandson of Stonewall Jackson. “We were trying to find the Lord to see if He would part the waters and open up an escape route from General Sherman’s march to the sea.” From a relatively poor family of Southern Baptists in rural Louisiana, she had lived in a state psychiatric hospital for almost three years. Her diagnoses ranged from borderline schizophrenia to temporal lobe epilepsy. The collateral interviews with her mother from several years before had been placed in the hospital chart. They recounted that in the patient’s middle to late teens she had become suddenly promiscuous, frequently approaching strange men in city parks. Obsessed with fellatio and swallowing sperm, she told her mother that she was receiving a holy sacrament. More recently, the increasing incidence of ecstatic episodes and compulsive note taking coincided with the complete loss of interest in sexuality in any form. Her talk was now full of moralizing detail about the shoulds and should nots of daily living. She referred to herself as a non-Catholic nun who was married HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_013517

Page 18 - HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_013518

to Christ. The brain waves recorded from electrodes deep in her brain demonstrated transient episodes of spiking in a midline limbic structure called the septum and in the right hippocampus, deep in the temporal lobe. Paul MacLean and others since have shown that electrical stimulation of these and related brain regions could produce pleasure and grooming reactions in cats and prolonged penile erections in squirrel monkeys. Many years later, | spoke about Donna with the Harvard professor of neurology, Norman Geschwind. He took me to his twice a week epilepsy clinic. In an effort to demonstrate what is now known as the Geschwind Syndromes of between seizure, inter-ictal personality changes in patients with temporal lobe epilepsy, he stood in front of the patients’ waiting room. In a loud voice, he asked that all people keeping diaries and personal notebooks please stand up. Several did so, some displaying their notebooks in outstretched hands. The pages that | saw were filled mostly with religious writing, biblical quotations and exclamation points. Gathering the positive responders together, he asked them in turn what religion they were. Several answered the question with the question, “When?” It turned out that many reported having several experiences of religious conversion. Geschwind called them “Jamesian Episodes” after William James’ Varieties of Religious Experience. He then asked when was the last time they engaged in sexual activity. For most of them, including those that were married, it had been years. Thought the men said they were not impotent, experiencing early morning spontaneous erections, they claimed a complete loss of interest in sex though feeling warmly affectionate toward people generally. As he anticipated, the patients were emotionally intense and unstoppably loquacious, needing to speak at length about their moral philosophies. They persisted in following us around the clinic waiting room, several speaking at once. In his lectures and papers, Geschwind called this last feature, difficulty in separation, interpersonal “stickiness.” First reported by the French electroencephalographer, Henri Gastaut, a history of multiple ecstatic religious experiences, increasing emotional intensity and lability, hyposexualilty (not impotence), moralizing religiosity, compulsive and frequently poetic writing and tendency to cling to people is now called the Geschwind Syndrome of temporal lobe HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_013518

Sponsored

Page 19 - HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_013519

epilepsy. Some say it is relevant to the likes of Apostle Paul, Sister Teresa and Joan of Arc. One evening in the human neurophysiology laboratory, | was invited by Dr. Heath to join him and several other brain scientists behind a two-way mirror to watch an interview with Donna while electrical current was being put through her recording electrodes. We watched and listened as a psychiatrist interviewed her about her past. The patient was speaking about her childhood. Unseen by the patient, the neurophysiologist, with us behind the mirror, was intermittently pushing the button evoking brain stimulation with very low current applied to the septum. Dr. Heath told me to listen for subtle changes or discontinuities in the flow of the on- going conversation that he said might reflect alterations in her thoughts and feelings. . “The first time we were allowed to take a break from Sunday school for the church service and | got to hear the choir and the pipe organ, | suddenly got a feeling of happiness that | hoped would last forever. My Sunday school teacher told us how much Jesus loved us and that’s what the music made me feel like. For the first time in my life | felt completely safe.” Though the two way mirror | saw the psychiatrist nod silently. “When | learned about the real meaning of Christmas and Easter, it was frightening and beautiful.” Within a few seconds after the neurophysiologist, behind the mirror and unseen by the patient or her interviewing physician, pushed the switch on the stimulus generator, the patient stopped talking. After a little more silence, her interviewer encouraged her to continue, “You were talking about how beautiful the holidays were. Tell me in what ways?” “| don’t want to talk about that anymore.” She blushed and looked very uncomfortable. The neurophysiologist's hand remained on the switch. She continued to speak with her psychiatrist. “| have to ask you a favor and | don’t know why. | hope you don’t get upset. The thought won't leave me alone.” She seemed embarrassed even as her body relaxed against the back of the chair languorously. 19 HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_013519

Page 20 - HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_013520

“Of course not, Donna. You know that with me you can say anything.” Her face reddening further, she stuttered something unintelligibly and then was silent. “Pardon me, Donna, | didn’t hear what you said.” “Would you mind if | rested my legs on your shoulders?” Further Readings for In Search Of The Miraculous The Hebrew Alphabet, A Mystical Journey, Edward Hoffman, Chronical Books, San Francisco, 1998 The Book of Letters, A Mystical Alef-bait, Lawrence Kushner, Jewish Lights Publishing. Woodstock, Vt., 1990 Studies in Ecstatic Kabbalah, Moishe lIdel, State University of New York Press, Albany, N.Y. 1988 Beyond the Human Species, The Life and Work of Sri Arubindo and The Mother, Georges van Vrekhem, Paragon House, St. Paul, MN, 1997 Bhagadvad Gita, Sri Aurobindo, Lotus Press, Twin Lakes, WI, 1995 Play of Consciousness, Swami Muktananda, Syda Foundation, South Fallsburg, NY, 1978 Alchemical Psychology, Old Recipes for Living in a New World, Thom F. Cavalli, J.P. Tarcher/Putnam, NY 2002 Studies in Schizophrenia, A Multidisciplinary Application to Mind Brain Relationships, Robert G. Heath, Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA 1954 20 HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_013520

Page 21 - HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_013521

Role of Pleasure in the Brain, Robert G. Heath, Harper-Row, N.Y. 1964 Psychiatric Aspects of Neurological Disease, D. Frank Benson and Dietrich Blumer, Grune and Straton, N.Y. 1975. Mathematics —The Music of Reason, Jean Dieudonne, Springer-Verlag, N.Y. 1991 Mathematics for the Liberal Arts, F. Richman, C.L. Walker, R.J. Wisner and J.W Brewer, Simon and Schuster, N.Y. 1998 The Feynman Lectures on Physics, R.P. Feynman, R.B. Leighton and M. Sands, Addison Wesley, Reading, MA, 1963 21 HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_013521

Sponsored

Page 22 - HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_013522

CHAPTER 2: DOESN’T EVERYBODY Varieties of religious experience and the potential they bring for personal change are embedded in and perturbative of our unique and common personalities. The obsessive compulsive may have an easier time with the rigid restrictions of Fundamentalism or be more resistant to the flagrancy of none rational mystical experience. The hysteric may find subjective evidence for the Holy Ghost more accessible and rules of behavior beside the point. The potential for double-jointed multiplicity in personal styles and quick transitions between them characterize what is called the borderline personality. |It is in these ways that temporary and permanent brain styles in us and important others supply much of the ground for the possibility of spiritual transformation and the often attendant alterations in personality. How can we think about this facilitator and source of resistance to new spiritual practice? A skinny, knobby kneed, small breasted, mousy haired, bright-eyed psychotherapy patient of mine at UCLA’s Neuropsychiatric Institute Outpatient Clinic was among the highest priced Santa Monica call girls serving Beverly Hills. Answering my unaskable question about her thousand-dollar fee, she explained that she was living proof that, in her profession, what was more important than physical beauty was “griv sense.” She explained that by her middle twenties, she had 22 HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_013522

Page 23 - HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_013523

developed the ability to anticipate the most highly prized but often embarrassing-to- say longing for a particular sexual act without being asked. She told me that she had to “empty out my personal sex manual” to feel the cravings of her clients. What the john most wanted appeared suddenly in her mind in the form of a cartoon. A university criminologist later explained that the word “griv” was probably derived from what pick pockets call grift sense, the ability to intuit who was likely to have enough money in their billfold to justify the risk, even if they appeared in the worn clothes and dated cars of old money. In his 1913 Dernieres Penses, Henri Poincare’, France’s seminal theorist in nonlinear dynamical systems theory, described intuition as a mental faculty which allows us to “...immediately see the end from afar...” In the context of mathematical epistemology, the instantaneous images of a geometer contrast with the labored sequential logic of the mathematical analyst. Poincare’ claimed that inclinations toward one or the other of these two cognitive styles and their associated mathematical tools arise from different kinds of minds. He contrasted the 19" Century German mathematicians, Weierstrass, who he said reduced his general tt theory of functions to “...a prolongation of arithmetic...without a single (pictorial) n figure in any of his books...” with Riemann who called geometry to his aid in describing functions. He created “...an image that no one can forget... once he understood it.” Experiencing the behavior of others, we create a set of anticipations about whom and how they are that align with parts of ourselves. Aware of one aspect of a person, we imagine the others. With a small amount of initial information, we connect the dots, fitting features we have seen and heard to personality configurations stored by informal category in our brain files. Our conclusions about them “being one of those” can both facilitate and impair our perceptions. Eastern metaphysicians, Western mystical religionists, socially liberal secular humanists, Shannon information theorists and today’s students of dynamical systems in brain and behavior can, in different ways, make the case that the content of these stereotypes reflect a pattern of constraints, our personal limitations resulting from the rutted roads of worldly experiences. Baba Muktananda, the Hindi Saint from the 23 HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_013523

Page 24 - HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_013524

Indian village of Ganeshpuri, called them our samsara. These limit the formlessness of anticipation that underlies sensibility. Our samsara reduces the uncertainty that could serve as grounds for new perceptions and understanding of others. Pre- emptive distortions reduce the bandwidth available for new information. They impair the range of empathic relations with others as well as ourselves. These restrictions in possibilities and choices are expressed in enduring patterns of behavior, thinking and feeling that mental health practitioners call personality and character. When confronted with these constrictions, the self justifying and diagnostically revealing thought about a feature of one’s personality is, “...doesn’t everybody? “ This pride in our shape contrasts with the teachings about emptiness of one of Baba’s favorite Indian holy men, Zipruanna, who sat all day, loin clothed naked in a garbage dump, instructing his students and followers about knowing and being nothing. We quantitate deficiencies in formlessness using statistical measures of entropy. They characterize the system’s behavior as a distance from the state of highest entropy also known as maximal randomness. Professor Karen Selz of Emory University did a study in which her human subjects, after taking a battery of personality inventories, were asked to remove as many dots as possible from a computer screen full of them in three minutes. They were to do so by left clicking on each of them with the mouse key. Two seconds after a dot was removed, it reappeared and became subject to removal again. As they went about the dot removal task and unbeknown to the subjects, the orbit inscribed by their dot removing mouse travels was recorded for later graphic representation and quantification. Most subjects with the usual broad mixture of personality traits inscribed a wide variety of orbital line styles: little wiggles, big wiggles, large and small loops, little smooth slides and big and little jumps. The counter-intuitive coupling of stylistic rigidity and whole system instability (as in non-hyperbolic fixed points described in the previous essay and below) is in evidence at the personality and graphical extremes of her subject group. A fastidious, rigidly organized, severely obsessive-compulsive subject repeatedly removes the same dot, only occasionally moving to a neighboring one to do more repetitious left key mouse clicking. Very little of the large computer screen 24 HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_013524

Sponsored

Page 25 - HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_013525

of possible mouse travels is occupied. All the action is centered on a small set of points. When such a minimal entropy person is injured and feeling helpless, their stuckness can grow bizarre. Ruminative fixation in self-critical and persecutory ideas extend into poisoned food anorexia, circular pacing, weight loss and middle- of-the-night, worried insomnia. Suffused with sin, they ask forgiveness for soiling the chair by their sitting in it or smelling up the room with their body odor. At the high entropic extreme, the mouse orbits of the seductively dramatic, new reality-creating hysteric includes big jumps, disorganized whorls and large and small restless and short attention span scribbles that tend to fill up the entire screen. The fragility of fixation at this end manifests itself in breakdown into impulsively out- of-control and floridly dramatic displays. Their decrease in contact with reality precipitates social chaos around them. The Montreal behavioral neurologist, Pierre Flor-Henry, using electroencephalographic and psychological test data, described the difference between these two extreme forms of personality expressions as the overly dominant expressions of one or another of the /eft obsessional or right hysteric hemispheric emotional styles. As examples, Flor-Henry said that a left half brain depression feels like hopeless and agitated indecision and the depression of the right brain is an experience of emptiness like homesickness. Left-brain happiness is being exactly correct and right brain joy rushes like being especially chosen. The church going obsessional resonates with the sermon of the punitive priest who invokes the tension and relief of sin and salvation. The practice can result in a life long addiction to the transient high of this temporary forgiveness. In other churches, the hysterical character gets spiritual respite in disassociative visitations of the Holy Ghost and attendant signs and wonders. At Wednesday night healing services, new hope arises from personal surrender in a floor hitting, backward collapse called dying in the Lord. Both of these antipodal personalities contrast with the more receptive state of in-between entropy (with enough entropy available to form messages) which predicts more flexibility and higher potential for undistorted information processing. Relatively style-less and ego-less people are more open to hearing a variety of Gods in themselves and others. High alertness 25 HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_013525

Page 26 - HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_013526

without presupposition, ecstatically aware and selfless, it is God’s gift realized, a joyfully awake and nonjudgmental empty state of transcendence. As we sit, we work at feeling this in the brain of the enigmatically smiling stone Buddha. The externally inactive state of high internal activity, the Bhagavad-Gita’s formlessness in the world of form, inaction in the world of action, has a natural mathematical representation in the simultaneously expanding and contracting motions of hyperbolic dynamics and its associated entropic descriptors. How can this kind of formlessness equip us for almost instantaneous knowing? In a resting state of uniform hyperbolicity that only looks like randomness, accurate impressions of others can arise quickly and from only a few data points of observation. In the late 1960’s, University of California mathematician, Rufus Bowen, proved the now famous shadow theorem. This says that in dynamical states of hyperbolicity, directly observable on the screen in computer simulations, the first few points of the on- going wild dynamical dance that appears to jump randomly from here to there on the computer screen, counter-intuitively will quickly outline the entire skeleton of its future global shape, its geometry, though more time of observation is required to realize this structure in full detail. The contracting motions on the stable surface of action, called a manifold, “iron down” all the points onto the unstable manifold that serves to outline the shape of the attractor of all starting points. In such a system, observation of just the first few points outline the whole. Intuition, anticipatory knowing and that which some call prophesy, may be expressions of the hyperbolic brain’s mind doing dynamical shadowing. To review briefly, hyperbolic brain flow is made up of three decomposable components: (1) The apparently predictable one along the main road of the action, going straight ahead and round and round on a throughway called the center manifold—analogous perhaps to what might be a sequentially logical development; (2) Intersecting the center manifold transversally is a field of influence moving the action away from the center manifold with out-of-the-box motion, exploring side paths of unpredictably new, creative possibility called the unstable manifold, we might think about inspired risk-taking, impulsive associations in thought; (3) Another transversally intersecting field of influence, which conservatively, rationally, “irons 26 HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_013526

Page 27 - HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_013527

down” the expansive flow back onto the road, the entire constrictive field called the stable manifold. This influence herds points into shadowing the main road of the dynamics, like the hair of the dog that stay close to the real body of the animal in motion. It is in this way that just a few often slightly off the mark points nonetheless shadow the real (called fiduciary) orbits of the attractor, outlining its global geometry with just a little information. The intuitive reason shadowing works Is built into these natural countervailing tendencies of hyperbolic dynamics, which on one hand tends to spread out nearby initial points and brings disparate others together. The latter inclination is the one that smoothes down the escaping points onto surfaces of actions that mathematicians call manifolds. However, the details of the orbital paths don’t look that orderly due to the mixing of the sequence of points in hyperbolic motion. The mixing process on manifolds has been analogized to that of the bundled pink loops of the stretching (expanding) and folding (contracting) taffy puller at the carnival candy stand. The process gets sequences of small particles of candy out of sequential order while maintaining the taffy’s overall geometrically ovoid shape. Disorder is local with the entropy being generated by the repeatedly shuffling of the line up of the original orbital sequence. This results in the impossibility of any point- to-point prediction for more than a few points even though the over all shape is maintained. Exactly what minute a habitually late sleeper awakes can’t be predicted. On the other hand, the skeletal manifold of the global structure is entirely in evidence from almost the beginning. Late risers remain late risers even without a precise, minute-to-minute, predictable schedule. It is also interesting that a uniformly hyperbolic dynamical system, unlike the fixed-point attractors of stylistic fixation, resist perturbation-induced changes in global dynamical form. In an apparent paradox worthy of metaphysical allusion, the dynamically hyperbolic kind of formlessness has structural stability. The global geometric predictability of this point-to-point, completely unpredictable system can be both the subject and object of Zen frustration and thoughtful meditation. During weekly professorial rounds at Los Angeles’s Neuropsychiatric Institute, | assigned a standard exercise for psychiatric residents on clinical rounds, 27 HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_013527

Sponsored

Page 28 - HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_013528

which involved limiting their contact with a patient to five minutes. This was followed by detailed discussion of everything we’d seen and heard. |’d ask them to predict what we’d find in the many pages of personal interviews and nurses observations in the clinic chart. The student psychiatrists with the most street smarts, called emotional intelligence by Daniel Goleman, were particularly quick at shadowing and thus predicting the patient’s global dynamical pattern. Do personality patterns exist? Evidence from biometric studies of the hereditary aspects of personality style in animals and humans suggest that relatively few global component properties underlie a variety of complicated-looking manifestations of behavioral style. Primary colors are the source of all hues. Harvard psychologist, Jerome Hagen, has reviewed the history of this idea in his book, Galen’s Prophecy. While there are differences among personality research programs, almost all rating scale and questionnaire-based studies result in clusters of traits that reflect statistically associated properties which when taken together are called temperament. This idea is close to what we mean by personality. These relatively few response clusters are given descriptive names such as introversion, extroversion, neuroticism, impulsivity, sociability, task persistence and tolerance of ambiguity. As defined by psychological inventories, studies of families show that these styles are heritable in the range of 60%. Hans Eysenck, in over four decades of work and more than 5000 published papers from London’s Maudsley Hospital, derived common global factors of personality using questionnaires. The best known was called the Eysenck Personality Inventory. His studies resulted in evidence for only a few fundamental behavioral axes, behavioral manifolds, which describe extremal properties of personality types analogous to stable and unstable manifolds: introversion- extroversion, shyness-sociability, low and high activity level and emotional constriction versus impulsivity. To make the issue of personality as dynamical system more realistically complex, we can call on some examples of the rich history of behavioral genetic studies using animals such as the mouse. They can be selectively bred for underlying personality factors, such as dominance, fear, aggression or exploratory 28 HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_013528

Page 29 - HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_013529

courage. Not surprisingly, social interactions, as configured by the mouse’s own personality style, contributed significantly to their behavioral patterns. As an example, the C57BL strain of laboratory mouse has strong tendencies toward impulsively wild behavior. To be anthropocentric and using Hagen and Eysenck-like behavioral dimensions, we could describe the C57BL mouse as exhibiting high psychotocism, P, energetic sociability, high energy, E, and low emotionality, low neuroticism, N. The C57BL also loves alcohol and will dominate the low E, shy, low P, retiring, alcohol avoidant, high N, emotional, anxious, frequently defecating albino BALB strain of mouse when they are placed together for a limited time in a novel situation during the daylight hours. Over a more extended time, however, the BALB mouse comes to dominate the C57BL, beginning with attacks in the dark and finally as the persistent and patient survivor over days of aggressive fighting. BALB’s low E, social fear eventually turns into rage and aggression. The C57BL is quick to mate and ejaculate but very slow to recover sexually, so that the less post-orgasmically refractory BALB also wins in long term sexual competition in a cage full of fecund females. Modern social psychological approaches to human personality are beginning to approach the interactions of genetic brain proclivities and collective social dynamics in this way. Employing Eysenck categories of personality characteristics, similar results about style as influenced by genetic selection can be seen in humans. The correlations between factor scores based on B. Loehlen’s studies using the California Personality Inventory in twins demonstrated as much as threefold higher correlations among identical twins for extroversion (E) and neuroticism (N) factors compared with matched fraternal twins. The primacy of some of the in-born biological roots of these personality styles is suggested by G. Methany’s finding of higher correlations between identical as compared to fraternal twins when studied at the age of two months. The similarities in personality and temperament measures included activity level, regularity, approach-withdrawal, intensity, persistence, distractibility and adaptability. More recent familial studies of the heritability of personality characteristics included childhood shyness, neuroticism, depressive symptoms, aggressiveness, 29 HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_013529

Page 30 - HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_013530

behavioral inhibition and anxiety, behavioral flexibility, narcissism, deviant motor activity levels, novelty seeking, harm avoidance and reward dependence. These studies were conducted by R.R. Crowe, J.F. Rosenbaum, A. Methany, and J.L Robinson and indicated familial congruity of these characteristics among first and second degree relatives in the range of 40-50%. This level of heritability in genetically unrelated family members was found to be less than 20%. Low entropy fixations of personality can also evolve developmentally. Experiments in young animals have shown that stress-induced high levels of adrenal hormones exaggerate the normal developmental process of trimming back unused neural connections, called pruning, the normally complexly over-grown sprouting pathways. The pruning actions of the pituitary-adrenal stress hormones come to dominate sprouting actions of neural growth factors and their protection of neuronal axonal branching and connections during development. The research program of Bruce McEwan of Rockefeller University and others document nerve cell loss resulting from the neurohormonal concomitants of stress. This reduction in neuronal connectivity and neuronal cell content has been conjectured to contribute to the pathological simplification of neuronal projections and neural network complexity, reducing information processing capabilities. The still intact machinery underlying the global patterns of neurological activity, such as those that underlie personality styles, is arranged around these pruned, unoccupiable holes of lost brain possibility. If this range of potential behavior is extremely reduced, the behavioral syndrome is often called a personality disorder. Those that have one are the predictable Johnny one notes of response to perturbation: thrash out, lie without reason, get drunk, binge on promiscuity, steal unneeded things from department stores, or withdraw into interpersonal isolation. A more abstract and quantifiable way of representing the pathological simplification-induced emergence of low entropy, stereotypical personality style is inscribed on the head stone of the post-suicidal grave of Ludwig Boltzmann. This father of modern statistical physics expressed the idea in the form of a transformation: the (maximal) entropy, S, of a system is the logarithm of the number,Q, of its available ways of being, (i.e., S = log ). That is, one way a 30 HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_013530

Sponsored

Page 31 - HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_013531

reduction in the dynamical entropy of a system can occur is by reducing the number of its available states. As the repertoire of ways of personal responding, log Q, is reduced, so is the brain system’s entropy, S. Reality constrained patterns of behavior, as in successfully adaptive personalities, lie in some optimal in-between place between the maximal and minimum measures of entropy. The dynamical state that is postulated to yield in- between-valued entropies is called nonuniform hyperbolicity. This is best seen when the values of the experimental observations are plotted in a two dimensional phase space with each point represented by two values: along the x-axis is plotted the value observed, along the y-axis is graphed the change in the value from the last observation. The signatory motions of these observations plotted in phase space are irregularly varying in rate of expansion (near by initial values are separating in time) and contraction (greatly differing initial values are coming together in time). Values are not fixed, rhythmically varying nor in random motion. These nonuniformly hyperbolic motions are seen in speeded up, talking head videos showing bursts of hand gestures and in normal neuronal activity. Silences have widely varying lengths and bursts of hand movements and neuronal discharges are irregular in duration and character. The statistical pattern of neuronal inter-burst intervals is not the convergent Gaussian distribution of |.Q. or heights but the nonconvergent, long tailed, Levy distribution of flood incidences and, according to Mandelbrot, stock market crashes. The labored logic and inscrutably compact mathematical formalisms of the Nobel Prize winning physicist, Ilya Prigogine, and his Belgian school, explain the thermodynamics of these long lasting niches of restricted variation in our personal style as energy requiring dissipative structures. Compulsive nail biting, driven promiscuity, readiness to be suspicious are seen as a persistence of deviations from the maximum entropy of formless, flexible, receptive end states. The system is trapped in possibility reduced, energy requiring, samsaric niches of what Prigogine called minimal entropy generation. We unique and oddly shaped and entropy leaking balloons maintain our characteristic distortions through energy-requiring, 31 HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_013531

Page 32 - HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_013532

persistent efforts at insufflation. The maintenance of neurotic defenses and eccentric habits can be fatiguing. The children at Kids in Distress Residential and Day Care Center in Southeast Florida, called KIDS, tended to be small for their ages. As a psychiatric consultant to the Center, | often summarized an evaluation of both their physical and intellectual development as “delayed.” Looking like almost completely formed adult-like personalities, however, they were developmentally “advanced.” | heard in a child analytic seminar at the Psychoanalytic Institute of Southern California that traumatized children often hurry through the dangerous developmental ambiguity of openness and flexibility to the predictable, fixed attitudes and behavior of adults. It was common to find prematurely wise young children serving as parents in chaotically dysfunctional families. In residence at the Center, set free from their pathogenic homes by social workers and family law judges, these premature caregivers lost sleep worrying about who was taking up their obligations to the sisters and brothers left behind. Trauma-induced possibility pruning was often obvious in the young refugees at Kids in Distress. Having been soaked in alcohol containing, nutritionally deficient, crack-laced amniotic fluid, young babies were then left in dirty cribs behind locked doors to cry themselves into exhausted despair. Their mothers were working the streets for drugs. The children that survived often demonstrate personality styles that are reduced in variety. They came to use a few, individualized, and stereotyped techniques for survival. Some children’s insulated detachment was_hollowly disguised as interpersonal caring. Others used driven and rigid compulsion to maintain the appearance of conscientious good citizenship. For some children, paranoid thoughts were realistic expectations. . Arriving at the Center | heard “Dr. Arnold! Dr. Arnold!’ in high-pitched screams. Several children ran up to me at once, demanding to be held. Some leaped into my arms for a hug. Trying to get and hold their visual gaze was another 32 HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_013532

Page 33 - HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_013533

matter. Their eyes darted back and forth across my face, not stopping at my eyes, as though checking for danger. It felt like a strange mix of physical clinging and interpersonal distantiation. Many articles in the International University Press’s Psychoanalytic Studies of the Child book series, described these prematurely formed child personality types: the paranoid scouts, the detached as /f children pretending to feel, the desperate to please obsessionals, the charismatically seductive hysterics and the unconscionable psychopaths. Experiments simulating trauma and neglect in young animals also demonstrate acceleration in biobehavioral development. Possibilities, the number of available states, ©, brain entropies as S = log Q, become casualties of traumatic and neglected early life. Like one trick ponies, these abused and abandoned children take up singular patterns of behavior that seem to work and stick to them. One doesn’t anticipate seeing such narrowly fixated personality patterns until late adolescence or adulthood. They appear at ages too young to qualify for the character pathology coding of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual IV. Yet the labels of adult personality disorder seem inescapable when one sees a four-year- old child trapped in a compulsive hand washing ritual or a panty flashing five-year- old girl with a seductive gait. Four-year-old Alicia rubbed the lumps in my right hip pocket containing caramel candies. Her blue eyes twinkled. Her long blonde hair was in bangs and her lips in a pout. She kept a hand on her hip and tilted her pelvis as she spoke. Listening to children’s stories, she straddled the reader's thigh and rocked. Alicia had a history of sexual abuse in a home that was a hang out for drug dealers. There were rumors that she talked to strange men late at night on the phone. On admission to the Center, she was found to have genital herpes. Both of her parents had been in and out of prison for drug-related crimes. The Center’s staff spoke of Alicia’s seductive smiles, incessant demands, irritable complaints and tantrums. With the back of her hand held against her forehead, she said that it was too hot to pick up the toys she had scattered around the fenced yard. Ordered to comply, Alicia took three steps into Florida’s summer heat and fainted. Each morning, she spent the better part of an hour in front of the mirror, trying on all four of her dresses 33 HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_013533

Sponsored

Page 34 - HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_013534

and their scarf and belt accessories before choosing one for her appearance at the breakfast table. Five-year-old Grace was a suspicious and dictatorial presence in the Center’s kindergarten class. Articulate and righteous, she confronted children and staff alike with evidence for the unfairness she found everywhere. In legalistic defense of her rights and sometimes those of her peers, she used her strong wide face, penetrating look and quick and observant mind aggressively. Her somewhat intimidated childcare worker maintained Grace's cornrowed hair with care. Sensitive to criticism and quick to anger, she competed with her teacher for control of the class. Her drug abusing young mother had escaped from her own mother’s authoritarian house, leaving six-month-old Grace in the care of her commanding grandmother, a matronly church elder. Recent studies by David Reiss and associates at George Washington University assessed psychosocial dynamics in genetically varied families. They found that genetic similarities amplified the expression of individual characteristics of interpersonal relating through what might be called personality resonance. Relatives often commented that Grace and her grandmother, being alike, deserved one another. Shortly after her fourth birthday Grace was removed from her grandmother's home while the circumstances surrounding the accidental scalding of the bottom half of her body in an overheated bath were being investigated. She began her first conversation with me, “Hey doctor baldy, why are your bottom teeth so crooked?” Damon was darkly handsome, with teasing eyes and a gleaming smile. Talking to his legal guardian on the pay phone in the afternoon of his second day at KIDS, he was heard to be making charges of mistreatment by the staff. He asked his guardian, loud enough to be heard throughout the day room, “What does it take to get someone fired around here?” Six years old and abandoned by his mother at the age of three, Damon came to KIDS with a history of provoking administrative conflicts at several children’s shelters. His record showed that once he successfully used accusations of beatings to get a staff member fired employing charges that were later shown to have been fabricated. He argued persuasively, manufacturing events and quoting imaginary conversations with smooth confidence. He could 34 HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_013534

Page 35 - HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_013535

change stories midstream without apparent loss of continuity or confidence. He learned the power of a claim of abuse, and used the threat of it to control his environment. Damon talked other children out of their candy allotments, cheated at games and stole clothes from other children’s lockers. Debbie, age eight, was the eldest of four children. Her mother was a street prostitute with an expensive drug habit. Debbie was thin, restless and worried. A self-appointed mother from the age of four, Debbie felt responsible for the care and feeding of her brother and two sisters. With a history of physical and sexual abuse by a series of her mother’s boyfriend-pimps, Debbie spent most of her time cleaning and recleaning their small apartment and worrying about obtaining enough food for her brothers and sisters. Her mother was often gone for one or two days at a time, and food supplies were not dependable. On several occasions, Debbie was caught stealing food from all night grocers. The investigative social worker reported that Debbie had learned to sell oral sex to the men who loitered behind a neighborhood bar. She used the money to buy food. For several days after admission to the crisis home, Debbie was anxious and sleepless. She worried endlessly about the welfare of her sisters and brother despite reassurances that they were in caring foster homes. She checked on them as frequently as allowed by phone. In a playroom therapy session, wielding a rubber knife, she pointed to a scar on her left forearm and told a story about the time that she cut herself with a kitchen knife and fed her blood to her infant sister when there wasn’t any food in the house. Debbie kept her room very tidy, did all her chores and sometimes those of other children. Even after several months in residence, always-busy Debbie didn’t have even one close relationship with any of the other children or members of the staff. Despite the superficial differences, there are subtle and pervasive similarities among the personality styles of Alicia, Grace, Damon and Debbie. Like overgrown and tasteless cabbages, pale and four feet across, growing from seeds over-treated with gibberellin or auxin plant hormones, the inner lives of these prematurely big little people are relatively empty of stable interpersonal objects. The pantheon of indwelling companions are either malignant, absent or both. There is a deficiency of internalized significant others with qualities we more healthy neurotics paste onto 35 HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_013535

Page 36 - HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_013536