HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_011472 - HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_011903

EB Draft Ch1-25

The document HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_011472 is a government record from the House Oversight Committee, consisting of 432 pages, and concerns a draft of chapters 1-25, potentially of a book or report, related to "EB".

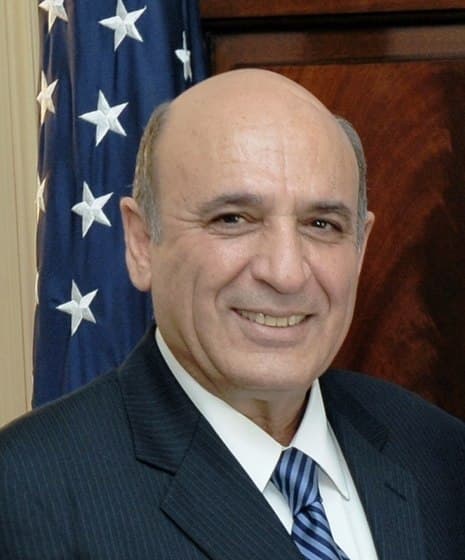

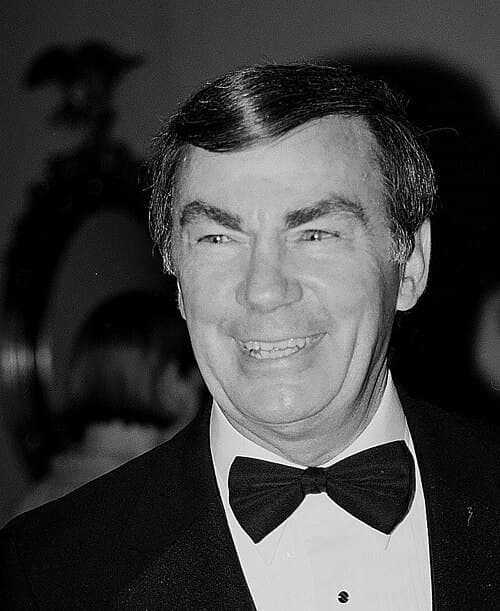

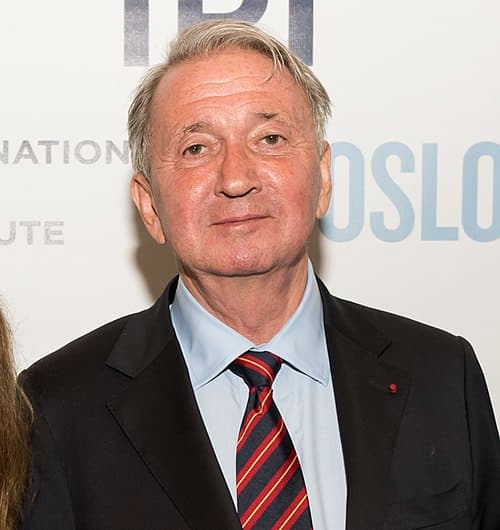

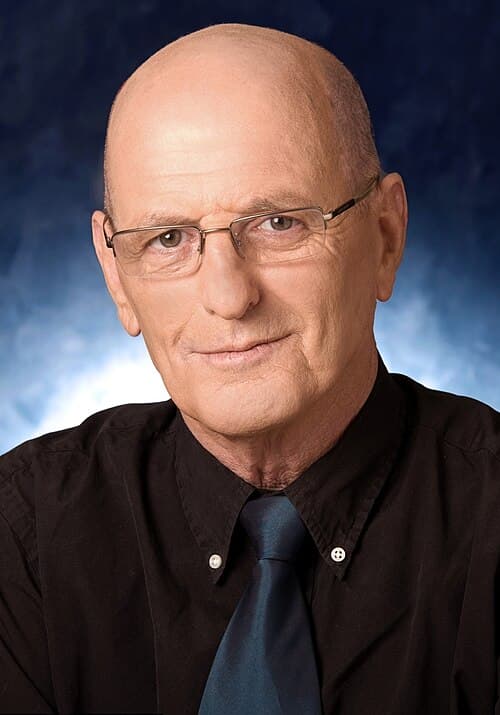

This document appears to be a draft of chapters, possibly for a book or report, given its reference to 'EB Draft Ch1-25'. The content preview features a reflective narrative, seemingly from the perspective of Benjamin Netanyahu as Prime Minister of Israel, recounting his experiences and mindset shaped by his time in the Sayeret Matkal special forces unit. The document touches upon themes of political disappointment, strategic evaluation, and the impact of special forces training on leadership.

Key Highlights

- •The document is a draft of chapters 1-25.

- •Benjamin Netanyahu reflects on his time in Sayeret Matkal and its impact on his leadership approach.

- •The narrative discusses political disappointments and the need for strategic evaluation.

Frequently Asked Questions

Books for Further Reading

Document Information

Bates Range

HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_011472 - HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_011903

Pages

432

Source

House Oversight Committee

Original Filename

EB Draft Ch1-25 PDF Sept 10 2017-Pnum.pdf

File Size

2.42 MB

Document Content

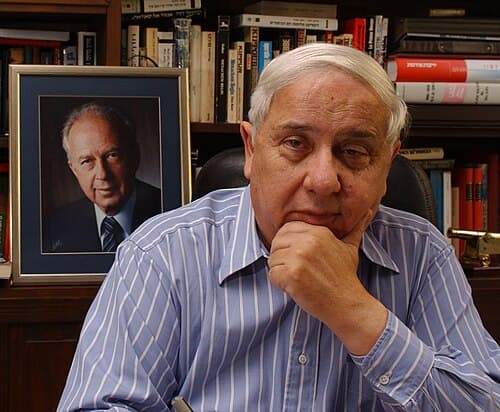

Page 1 - HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_011472

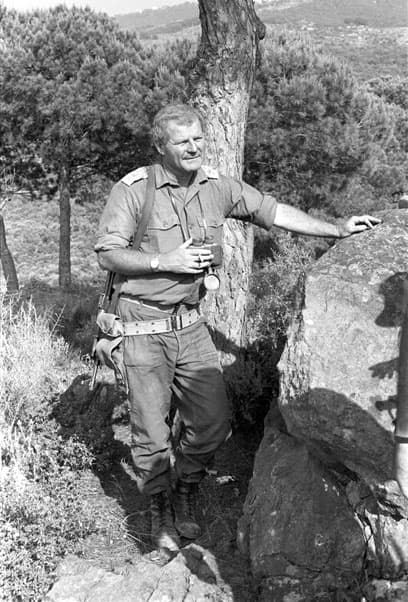

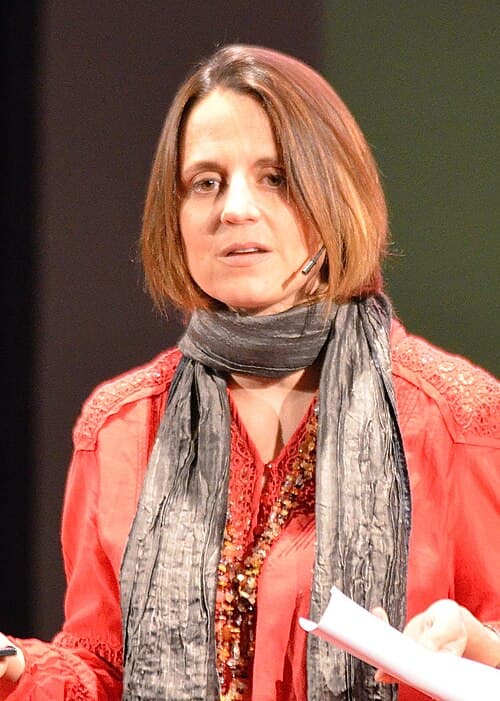

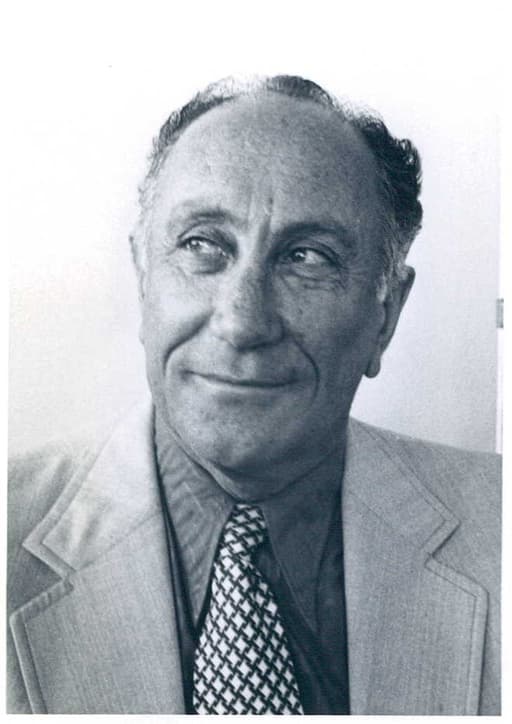

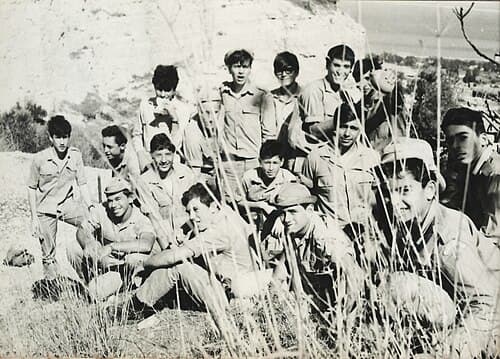

Night Flight They say that you can read a person’s feelings on his face. But if so, either I’m a very good actor — the opposite of what anyone who has worked closely with me would tell you — or the journalists clustered in front of me weren’t very good face-readers. They said that I looked defeated. Distressed. Depressed. Yet as I delivered my brief final statement outside an olive-green cabin at Camp David, the American presidential retreat in the forested Catoctin hills north of Washington, I felt none of those things. Yes, I was disappointed. I realised that what had happened over the last 14 days, or more crucially what had not happened, was bound to have serious consequences, both for me personally, as Prime Minister of Israel, and for my country. But I had been a politician, at that point, for all of five years. By far most of my life, I had spent in uniform. As a teenager, small and slight and not even shaving yet, I was one of the founding core of a unit called Sayveret Matkal, Israel’s equivalent of America’s Delta Force, or Britain’s SAS. It may be that the way I thought and acted, the way I dealt with danger or with crises, came from someplace inside me. Even as a young kid, I was always quiet, serious, contemplative. But my 13 years as a part of Israel’s main special-forces unit, especially once I became its commander, etched those qualities more deeply. And they added new ones: a sense that you could never plan a mission too carefully or prepare too assiduously; an understanding that what you thought, and certainly what you said, mattered a lot less than what you did. And above all the realisation that, when one of our nighttime commando operations was over, whether it had succeeded or failed, you had to take a step back. Evaluate things accurately, coolly, without illusions. Then, in the light of how the situation had changed, you had to decide how best to move forward. That approach, to the occasional frustration of the politicians and diplomats working alongside me during this critical stage of Israel’s history, had guided me from the moment I became Prime Minister. In my very first discussions with President Clinton a year earlier — a long weekend, beginning at the White House and moving on to Camp David — I had mapped out at great length, in great detail, every one of the steps I knew we would have to take to confront the central issue facing Israel: the need for peace. 1 HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_011472

Page 2 - HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_011473

In choosing to return, now, to Camp David for two weeks of summit talks, I knew the risks. Of all the moments of truth in my life — and in the life of my country — few, if any, would carry higher stakes. Success would mean not just one more stutter-step away from our century-long conflict with the Palestinians. It would signal a real, final peace: in treaty-speak, end of conflict. Whatever the complexities of putting an agreement into practice, given all the suffering and bloodshed endured by both sides, we would have crossed a point of no return. There would be two states, for two peoples. And if we failed? I knew, if only from months of increasingly stark intelligence reports, that an explosion of Palestinian violence — not just with stones or bottles this time, but with guns and explosives — would be only a matter of time. I knew something else as well. This would be a moment of truth not just for me. Or for Bill Clinton, a man who understood our conflict more deeply, and was more determined to help us end it, than any other president before him. It was a moment of truth for the leader of the Palestinians, Yasir Arafat. The Oslo Accords of 1993, groundbreaking though they were, had created a peace process, not peace. Over the past few years, that process had been lurching from crisis to crisis. Political support for negotiations was fraying. And yet the core issues of our conflict had not been resolved. In fact, they had hardly been talked about. The reason for this was no secret. For both sides, these questions lay at the heart of everything we’d been saying for years, to the world and to ourselves, about the roots of the conflict and the minimum terms we could accept in order to end it. At issue were rival claims on security, final borders, Israeli settlements, Palestinian refugees, and the future of ancient city of Jerusalem. None of these could be resolved without painful, and politically perilous, compromises. Entering the summit, despite the pressures ahead, I was confident that I, with my team of aides and negotiators, would do our part to make such a final peace agreement possible. Nor did I doubt that President Clinton, whom I had come to view not just as a diplomatic partner but a friend, would rise to the occasion. But as for Arafat? There was simply no way of knowing. That was why I had pressed President Clinton so hard to convene the summit. That was why, despite the misgivings of some of his closest advisers, he had taken the plunge. We both knew that the so-called “final-status issues” — 2 HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_011473

Page 3 - HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_011474

the substance of any real peace — could not simply be put off forever. Untangling them was getting harder, not easier. And we realised that only in an environment like Camp David — a “pressure cooker” was how I described it to Clinton, and to US Secretary of State Madeleine Albright — would we ever discover whether a peace deal could in fact be done. Now, we knew. Israel’s equivalent of Air Force One, perhaps in a nod to our country’s pioneering early years, was an almost prehistoric Boeing 707. It was waiting on the runway at Andrews Air Force Base outside Washington to ferry me and the rest of our negotiating team back home. It contained a low-rent equivalent of the American version’s presidential cabin, and a few 1960s-vintage first-class seats, but consisted mostly of two long lines of coach seats, three abreast, separated by an almost tightrope-narrow aisle. I dare say I was alone in finding an odd sense of comfort in boarding the plane. This museum piece of an aircraft was part of my past. It was the same model of 707 for which I, with a couple of other young soldiers and engineers, had come up with what we dubbed the “submarine door” system outside the cockpit — to protect El Al pilots from future attacks after one of its planes had been hijacked to Algiers in the summer of 1968. It was also the same kind of plane — a Sabena flight, hijacked to Tel Aviv’s Ben-Gurion Airport — which I stormed, before sunrise, four years later with a force of nearly two dozen Matkal commandos. The shooting was over within 90 seconds. One of my men —a junior officer named Bibi Netanyahu — was wounded. By one of our own bullets. But we managed to kill two of the heavily armed hijackers, capture the others, and free all 90 passengers unharmed. Still, even I had to accept, it was no fun to fly on. As we banked eastward after takeoff and headed out over the Atlantic, the mood on board was sober. Huddling with the inner core of my negotiating team — my policy co-ordinator Gilad Sher, security aide Danny Yatom and Foreign Minister Shlomo Ben-Ami — I could see that the way the summit ended had hit them hard. It was probably true, as all three often reminded me, that the greatest pressure fell on me. I was the one who ultimately decided what we could, or 3 HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_011474

Sponsored

Page 4 - HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_011475

should, offer in search of a true peace with the Palestinians. I was the one who would be blamed by the inevitable critics, whether for going too far or not far enough, or simply for the fact the deal had eluded us. I knew the drill: the same thing had happened when I had come tantalizingly close to finalizing a peace deal with Syria’s then-dying dictator, Hafez al-Assad, a few months earlier. Yet these three dedicated men — Gili, who was by training a lawyer; Shlomo, an academic; and Danny, a former Mossad chief — had just been through dozens of hours of intricately detailed talks with each of Arafat’s top negotiators at Camp David, not to mention the dozens of other meetings before we had even got there. Now they had to accept that, even with the lid of the pressure cooker bolted down tight, we had fallen short of getting the peace agreement which each of us knew had been within touching distance. I don’t think that even they could be described as depressed. On our side, after all, we knew we had given ground on every issue we possibly could, without facing full-scale political rebellion at home. We had proposed an Israeli pullout from nearly all of the West Bank and Gaza. A support mechanism for helping compensate tens of thousands of Palestinian refugees from the serial Arab-Israeli conflicts of the past half-century. And most painfully and controversially — my rivals and critics back home were already accusing me of “treachery” — we had agreed to let President Clinton present a proposal for the Palestinians to get sovereignty over the Arab neighbourhoods of Jerusalem as well as “custodial sovereignty” over the Haram al-Sharif, the mosque complex perched above the Western Wall, the holiest site in Judaism. But precisely because we had been ready to offer so much, only for Arafat to reject it all, even as a basis for talks on a final deal, I could sense how gutted my key negotiators were feeling. Still, I’m sure none of them was surprised when my own old operational instincts kicked in. In my statement to journalists, I had been careful to say that Arafat was not ready at this time to make the historic compromises needed for peace. But before parting with President Clinton and Secretary Albright, I’d been more forthright. It was clear, without my saying so, that the chances of our getting a peace agreement on Clinton’s watch were now pretty much over. He had barely five months left in office. Yet my deeper fear was that with Arafat having brushed aside an offer that went far further than any other Israeli had proposed — far further than the Americans, themselves, had expected from Israel — the prospects for peace would be set back for years. Perhaps, I said, for two decades. 4 HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_011475

Page 5 - HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_011476

The challenge now, I told my exhausted team, was to make sure we were prepared for this new reality. Part of the spadework was already in place. Much as I’d hoped that Arafat and I could turn a new page in Middle East history, I had directed our army chief-of-staff, nine months before the summit, to draw up contingency plans for the likelihood of an unprecedentedly deadly eruption of Palestinian violence if we were to fail. Now, I felt we had to go even further, and to prepare a proactive alternative to the negotiated deal we’d been unable to secure. I proposed considering a unilateral Israeli pullout from the West Bank and Gaza. The territorial terms would, necessarily, be less far-reaching than the proposal Arafat had rejected. But I felt we should still withdraw from the great majority of the land we had captured in 1967, still leaving the Palestinians an area which the outside world would recognize as wholly sufficient for them to establish a viable, successful state. And crucially, this would finally give Israel, our country, a delineated, final border with the territory captured in the Six-Day War. Gili, clearly uneasy about accepting the idea that the chances for a negotiated peace were definitively gone, left to try to get some sleep on the long flight ahead. Danny and Shlomo Ben-Ami as well. Within an hour or so, the plane was full of irregularly slumped bodies, the silence broken only by the drone of the 707’s engines and the occasional sound of snoring. I sat, wide awake, in one of the seats at the front. My sleeping habits were another inheritance from Sayveret Matkal. During those years, nearly everything of significance which I did had happened after sundown. The commando operations were, of course, set for darkness whenever possible. The element of surprise could mean the difference between success and failure, indeed life and death. But all of my planning, all my thinking, tended to happen at night as well. The quiet, and the lack of distractions, helped to discipline my mind. I found that it helped to free my mind as well, sometimes only to discover that it went off in unexpected directions. It did so now. Perhaps even I was still reluctant to accept that Camp David meant that the opportunity for a transformative deal with Arafat was finished. Yet whatever the reason, I began thinking back to the first time that my path and his had crossed. It was in the spring of 1968, nearly a year after Israel had defeated the armies of our three main Arab enemies — Egypt, Syria and Jordan. Israeli forces were advancing on a Jordanian town called Karameh, across the 5 HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_011476

Page 6 - HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_011477

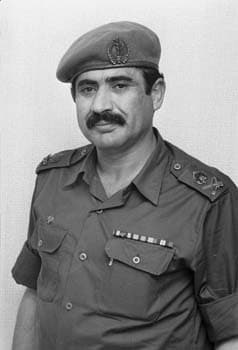

Jordan River from the West Bank, from which a fledgling group called Fatah, under the command of Arafat, had been staging a series of raids. In one of their most recent attacks, they’d planted land mines, one of which destroyed an Israeli schoolbus, killing the driver and one of the teachers and injuring nearly a dozen children. The so-called Battle of Karameh was our single most significant operation since the 1967 war. In pure military terms, it succeeded. But at a price: more than two dozen Israeli soldiers dead. It also had a major political impact. It caused shock among many Israelis, still wrapped in a sense of invincibility from the Six-Day War, as well as a feeling in the Arab world, actively encouraged by Arafat and his comrades, that compared to the great armies Israel had defeated in 1967, Fatah had at least shown fight. Fatah had drawn blood. I had just turned 26 years old. I was finishing my studies in math, physics and economics at the Hebrew University in Jerusalem, and had joined my Sayeret Matkal comrades the night before the assault. It was a huge operation: ten battalions, including crack infantry units. Our own role was relatively minor. We were to seal the southern entrance to the town. But it proved a tough slog just to get there. Our vehicles got bogged down in mud. By the time we arrived, Fatah fighters, although many were in civilian clothes so we couldn’t be sure, were racing past us in the other direction. One of them, we were later told, was Yasir Arafat. On a motorcycle. It would be nearly three decades before the two of us actually met — shortly after the assassination of my longtime comrade and friend Yitzhak Rabin, when I had become Foreign Minister under Shimon Peres. But in the intervening years, Arafat was rarely off of my radar. By the early 1970s, he and his fighters had been expelled by King Hussein’s army from Jordan and were re-based in Lebanon. Arafat was becoming a significant figure on the Arab and world political stage, and an increasingly uncomfortable thorn in Israel’s side. I was head of Sayeret Matkal by then. Over a period of months, I drew up a carefully constructed plan — a raid by helicopter into a Fatah-dominated area in southeastern Lebanon, during one of Arafat’s intermittent, morale-boosting visits from Beirut — to assassinate him. My immediate superior, the army’s head of operations, was all for our doing it. But the chief of military intelligence said no. Arafat, he insisted when we met to discuss the plan, was no longer the lean, mean fighter we had encountered in Karameh. “He’s fat. He’s a politician. He is not a target.” 6 HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_011477

Sponsored

Page 7 - HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_011478

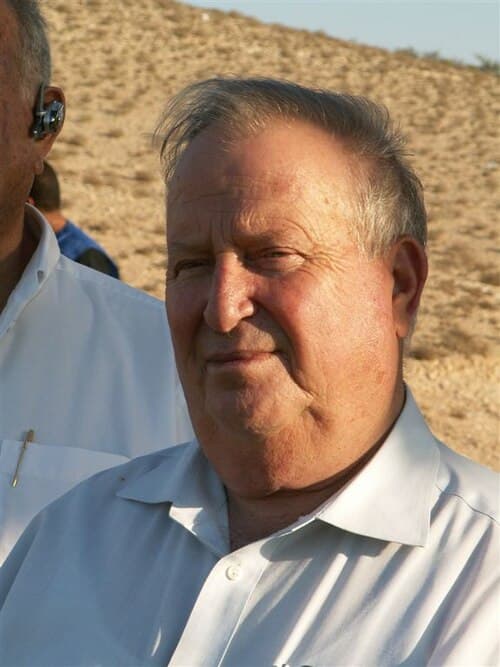

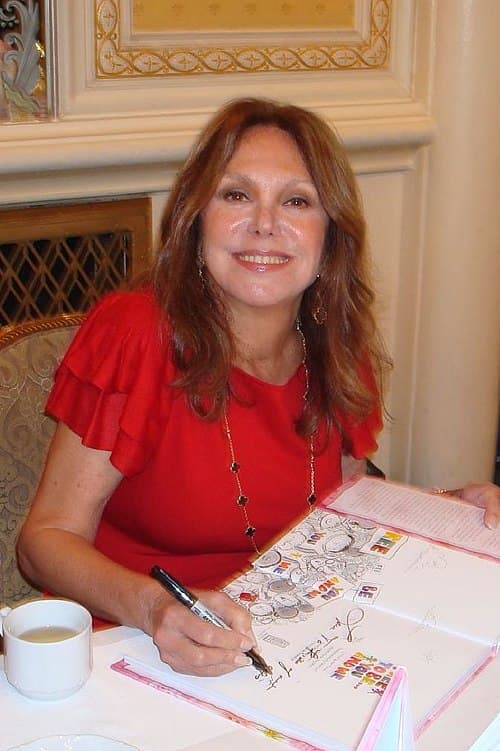

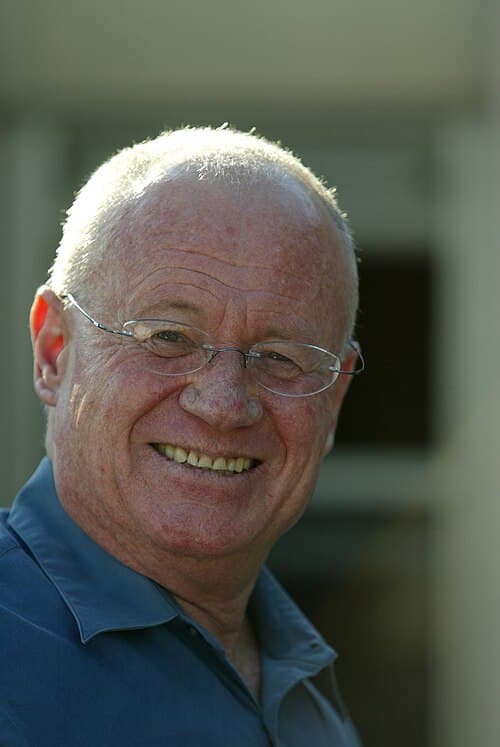

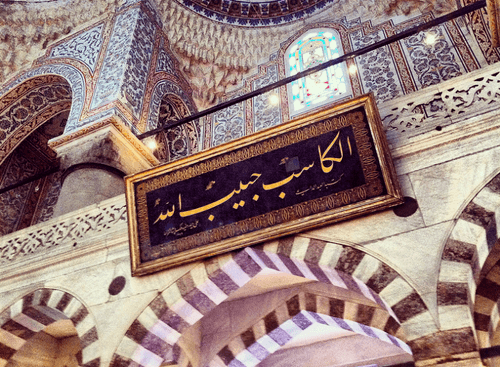

A decade later, the idea would suddenly resurface. In my first meeting, as a newly promoted Major General, with our then Defence Minister Ariel Sharon, Sharon turned to me and the army’s Chief of Staff, Rafael Eitan, and said: “Tell me. Why the hell is Arafat still alive?” He looked first at Raful, then at me, and added: “When I was 20 years younger than you are, I never waited for someone like Ben-Gurion or Dayan to ask me to plan an operation. I would plan it! Then I’d take it to them and say, you’re the politicians, you decide, but if you say yes, we'll do it.” I smiled, telling him that I’d done exactly that, a decade earlier, only to have one of his mates in the top brass say no. Sharon now said yes. But the plan was overtaken: by his ill-fated plan to launch a full-scale invasion of Lebanon in 1982, targeting not just Arafat, but with the aim of crushing the PLO militarily once and for all. I finally met Arafat face-to-face at the end of 1995. Although the Oslo peace process had dramatically changed things, it was clear that the real prize — real peace — was still far away. We were in Barcelona, for a Euro-Mediterranean meeting under the auspices of King Juan Carlos, aimed at trying to re-invigorate negotiations. The ceremonial centrepiece of the event was a dinner at one of the royal palaces, and it was arranged for me and Arafat to meet for a few minutes beforehand. | arrived first. I found myself in a breathtakingly opulent, but otherwise empty, room. Empty, that is, except for a dark-brown Steinway piano. From childhood, I have loved music. And while I am never likely to threaten the career of anyone in the New York Philharmonic, I have, over the years, developed some ability, and drawn huge enjoyment, as a classical pianist. I pulled back the red-velvet bench and began to play. With my back to the doorway, I was unaware that Arafat had arrived, and that he was soon standing only a few feet away, watching as I played one of my favourite pieces, a Chopin waltz. My old commando antennae must have been blunted. I may not have become “fat”. But, undeniably, I was now a politician. When I finally realised Arafat was behind me, I turned, embarrassed, stood up, and grasped his hand. “It’s a real pleasure to meet you,” I said. “I must say I have spent many years watching you — by other means.” He smiled. We stood talking for about 10 minutes. My hope was to establish simple, human contact; to signal respect; to begin to create the conditions not to try to kill Arafat, but to make peace with him. “We carry a great responsibility,” I said. “Both of our peoples have paid a heavy price, and the time has come to find a way to solve this.” 7 HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_011478

Page 8 - HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_011479

I sensed, at the time, at least the start of some connection. I suspected that Arafat viewed me, as he had Rabin before me, as a “fellow fighter”. But if so, I now wondered whether that might have been part of the problem in his ever truly understanding my mission at Camp David. My motivations. Or my mind. Even in Israel, my reputation as a soldier has sometimes been as much a burden as an advantage. A whole body of stories has followed me from my 36 years in uniform — a career which, after Saveret Matkal, led me up the military ladder until I was head of operations, intelligence, and eventually of the entire army as Chief of Staff. By the time I left the military, I was the single most decorated soldier in our country’s history. Some of the stories were actually true: that when we burst onto the hijacked Sabena airliner, for instance, we were dressed as a maintenance crew; or that, in leading an assassination raid in Beirut against the PLO group that had murdered Israeli athletes at the 1972 Munich Olympics, I was disguised as a woman. Not the most attractive young lady, perhaps, though I did, painfully, pluck my eyelashes, and, with the help of four pairs of standard-issue Israeli Army socks, develop quite a comely bosom. I rejected the idea of wearing a long dress, in favour of stylishly flared trousers. I was going on a commando operation, after all, not a prom date. But I did wear heels. So yes, a woman, of sorts. Yet some of the stories were just plain myth. I had given up counting the times I’d heard about my alleged prowess in recording the fastest-ever time on the most gruelling of the Israeli army’s obstacle courses. In fact, I was a lot more like Goldie Hawn in Private Benjamin. The main misunderstanding, however, went deeper. The assumption appeared to be that my military achievements, especially in Sayeret Matkal, were down to a mix of brute force and raw courage. Courage, of course, was a requirement: the willingness to take risks, if the rewards for success, or the costs of inaction, were great enough. Few of the operations I fought in or commanded were without the real danger of not coming back alive. But whatever success I'd had as a soldier, particularly in Matkal, was not only, nor even mainly, about biceps. It was about brains. The ability to make decisions. To withstand the pressure of often having to make the most crucial decisions within a matter of seconds. It was, above all, about thinking and analyzing — and always, always, looking and planning ahead. And as our plane droned onward towards Israel, I knew that I would now need all of those qualities more than ever. 8 HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_011479

Page 9 - HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_011480

This book is only in part the story of my life — a life that, from my beginnings as a kibbutz boy in pre-state Palestine, has been intimately entwined with the infancy and adolescence and, now, the increasingly troubled middle age of the State of Israel. Still less is it only a record of its, or my, achievements, although they are inevitably a part of the story. In setting out to write it, I was also determined to document, from the inside, the critical setbacks as well. Mistakes. Misjudgements. Missed opportunities. And the lessons that we can, and must, be prepared to learn from them. No less so than I when I was planning a hijack rescue or a cross-border commando operation in Saveret Matkal, | remain convinced that Israel’s security, Israel’s very identity, can be safeguarded only by evaluating dispassionately the situation in our country and the world. And by looking ahead. Even when I was a soldier, I never stopped thinking this way, especially when, first as military intelligence chief and especially as Chief of Staff, I knew, in detail, every one of the security threats that faced Israel and was part of discussions and decisions to try to confront them. I still vividly remember as Chief of Staff, every Friday before the arrival of the Jewish Sabbath, sitting with Rabin, who was then Israel’s Defence Minister. Our offices were along the same hallway of the Airya, the ministry’s headquarters in the heart of Tel Aviv. Rabin had a very low table in his office, with two chairs. We would sit across from each other, each with a ready supply of coffee and Yitzhak smoking an apparently endless supply of cigarettes, and we would just talk. Politics. Strategy. Israel. The PLO. The surrounding Arab states. And the wider world. Many years before I became Prime Minister, I gave a lecture at a memorial meeting for an Israeli academic. Not many people were there. I doubt even they remember it. But I do, because what I said has, sadly, become more prophetic than even I could have imagined. I talked about the imperative for peace as part of Israel’s security. There was a “window,” I said. We were militarily strong. In regional terms, we were a superpower. But politically, resolving the conflict with our Arab enemies would almost certainly become more difficult with time. 9 HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_011480

Sponsored

Page 10 - HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_011481

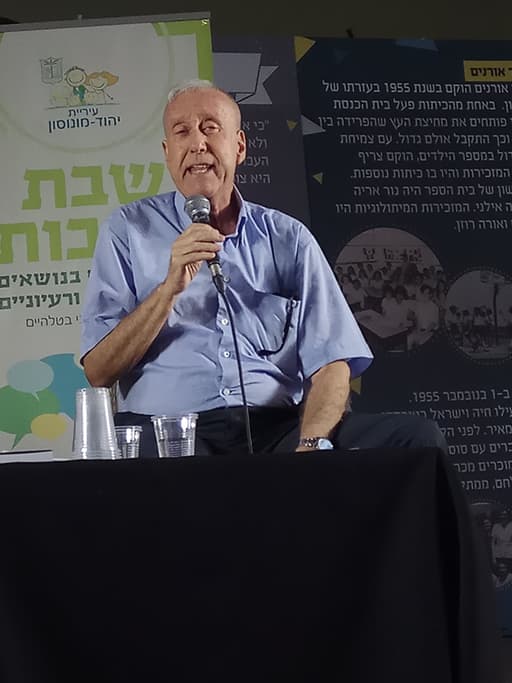

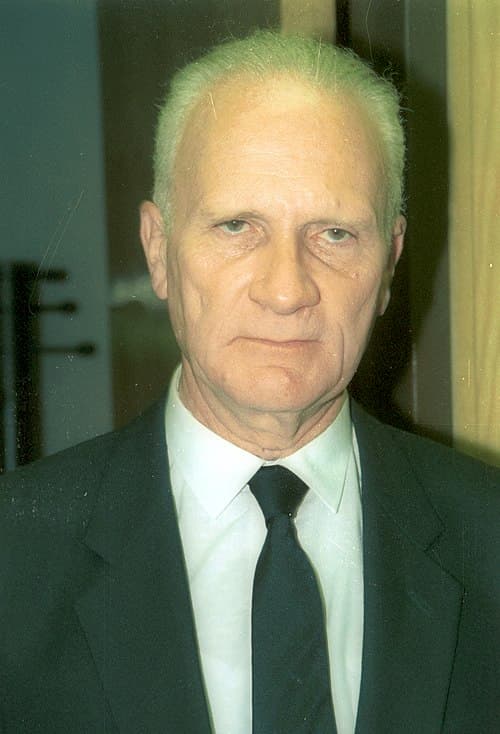

Iraq, perhaps Iran and other Middle Eastern states, might get nuclear weapons. A violent form of fundamentalist Islam could, over time, erode existing Arab and Muslim states, threatening Israel of course, but also the stability of our neighbourhood and of the world. In those circumstances, even if an Israeli government was strong enough, wise enough, forward-looking enough to pursue avenues for negotiated peace with its immediate neighbours, getting the popular support required would be all but impossible. The window 1s still there. But it is only barely open. I fear that I was right, as well, in predicting that our failure to secure a final peace agreement with the Palestinians at Camp David might set back peacemaking not just for a few months, but for many years. I have persisted in trying, very hard, to make that particular prediction prove wrong. That was why, despite intense pressure from my own political allies not to do so, I decided to return to government in 2007 as Defence Minister. I remained in that role for six years: mostly in the current, right-wing Likud government of my onetime Sayeret Matkal charge, Bibi Netanyahu. Much of what I say in this book about war and peace, security and Israel’s future challenges, will make uncomfortable reading for Bibi. But very little of it will surprise him, or his own Likud rivals further to the right, like Foreign Minister Avigdor Lieberman and the Economy Minister, Naftali Bennett. I have said almost all of it to them behind closed doors in the past few years, more than once. When I finally decided to leave the political arena last year, it was largely because I realized that they were guided by other imperatives. In the case of Bibi, the most gifted politician with whom I’ve worked except for Clinton, the priority was to stay in power. For Avigdor and Naftali, it was to supplant Bibi, when the opportunity was ripe, as Likud leader and as Prime Minister. And much too often — as with their hugely ill-advised recent proposal to amend Israel’s basic law to define it explicitly as a Jewish state, and deny “national rights” to non-Jews — the three of them have ended up competing for party political points rather than weighing the serious future implications for the country. Peacemaking, as I discovered first-hand, requires taking risks. Statesmanship requires risks. Politics, especially if defined simply as staying in power, is almost always about the avoidance of risk. 10 HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_011481

Page 11 - HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_011482

The problem for Israel, no matter who or what party is in government, is that there are risks everywhere one looks, and they show every sign of getting more, not less, serious. The “Arab Spring” has morphed into an Islamic winter. National frontiers that were put in place by British and French diplomats after the fall of the Ottoman Empire are vanishing. Centuries-old conflicts between tribes and rival religious communities have reignited. The old Cold War system of nations has given way to a world without a single geopolitical centre of gravity. Perhaps most seriously, Iran seems determined to get nuclear weapons, and, in my view, may succeed in doing so. Where Israel is concerned, relations with our indisputably most important ally, the United States, are more strained than at any time in decades. Diplomatic ties with Europe, our single largest trading partner, have been growing steadily worse. And the only real certainty is that anyone who tells you that they know absolutely where things are heading next is lying. Just ask Hosni Mubarak, who, despite having nearly half-a-million soldiers and security operatives at his disposal, was utterly blindsided, and very soon toppled and imprisoned, by an uprising that began with a sudden show of popular anger in Cairo’s Tahrir Square. Internally as well, Israel faces dangers. Chief among them is the alarming erosion of the standards of civil discourse, amid the increasingly shrill, often hateful, divisions between left and right, secular and religious, rich and poor and, most seriously of all, Jews and Arabs. While we remain economically successful, the fruits of our wealth are being ever more unevenly shared, and the prospects for continued growth constrained by the lack of any visible prospect of long-term peace. Bibi Netanyahu, of course, knows all of this. Indeed, he has repeatedly spoken of the multiple threats Israel faces, not only in somber terms, but at times almost apocalyptically. That works, politically. Politicians, not just in Israel but everywhere, know that it is a lot easier to win elections on fear than on hope. Yet my own prescription — learned, as this book recounts, from years on the battlefield, then reinforced by my years in government — is that Israel must resist being guided by either of those alternatives. Not fear, certainly. But neither by simple, untempered hope. Though the stakes have become much higher since my night flight back from Camp David nearly 15 years ago, our 11 HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_011482

Page 12 - HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_011483

need remains what I tried to impress on my negotiators then: realism. A meticulously informed, utterly unvarnished, understanding of the threats we face, of each altered situation after every success or a failure, and an ability to set aside the background noise and political pressures and chart a way forward. So what is that way? It begins with the mindset. On more than one occasion in the past few years, after Prime Minister Netanyahu had warned our country of a nuclear Iran or the spread of Al Qaeda-style hatred and violence, as if prophesying the coming of Armageddon, I would say to him: “Stop talking like that. You’re not delivering a sermon in a synagogue. You’re Prime Minister.” Having been privileged to live my own life along with the entire modern history of our country, I went further. Zionism, the founding architecture of Israel, was rooted in finding a way to supplant not just the life, but the way of thinking, which hard-pressed Jewish communities had internalised over centuries in the diaspora: in Hebrew, the galut. We would instead take control of our own destiny, building and developing and securing our own country. Now, I told Bibi, he was back in the mindset of the galut. Yes, al-Qaeda, and more recently Islamic State, were real dangers. The prospect of a nuclear Iran was even more so. “But the implication of the way you speak, not just to Barack Obama or David Cameron, but to /sraelis, is that these are existential threats. What do you imagine? That if, God forbid, we wake up and Iran is a nuclear power, we’ll pack up and go back to the shtetls of Europe?” Of course not. Israel, as my public life has taught me more than most, remains strong militarily. We are, still, fully capable of turning back any of the undeniable threats on our doorstep. Keeping that strength, developing it and modernizng it, are obviously critically important. But as Israel’s founding Prime Minister, David Ben-Gurion, used to say, the success of Zionism, and of the Israeli state, required two things: strength and “righteousness.” He didn’t mean the word in purely religious terms. He meant that Israel, if it were to retain international backing and internal cohesion, must be guided by a core of moral assumptions as well. That, in itself, would be reason enough to pursue every possible opportunity for “end of conflict” with our neighbours. And, at home, to protect and re- inforce our commitment to Israel as both a Jewish and a democratic state. But Israel’s simple self-interest — its hope for prosperity, social cohesion, and growth in future — makes this nothing short of imperative. 12 HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_011483

Sponsored

Page 13 - HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_011484

Bibi is right about one thing. The negotiating challenges have become more difficult since Arafat’s refusal of our offer at Camp David. Arafat is no longer alive. Palestinian politics have become ever more fragmented and messy, not least as a result of the Hamas takeover of Gaza. But Churchill once said that the difference between a pessimist and an optimist was that the pessimist always saw difficulties in every opportunity. The optimist saw opportunities in the difficulties. I, of all people, do not look at such opportunities without hard-headed analysis, even a dose of scepticism. But the opportunities are undeniably there, and never has Israel risked paying a higher price for failing to see and at least to try to act on them. The first port of call should still be the Palestinians. I have repeatedly asked Bibi, and the right-wing rivals that seem often to loom large in his political calculations: “If you’re so sure you don’t have a negotiating partner in the Palestinians, who not at least try? Seriously. What do you have to lose?” But beyond this, there is a whole range of relatively moderate countries — and, as Sunni states, strongly anti-Iranian countries — which share with Israel a real, practical interest in putting in place a new political arrangement in the Middle East. So does the United States, Russia, even China. Each, in their own ways, is threatened by a terror threat that will require international action, and many years, finally to defeat. A Saudi “peace plan’, for instance, has been on the table for years. Formally endorsed by the Arab League, it proposes a swap: Israeli withdrawal for full and final peace and Arab recognition. Successive Israeli governments have dismissed it out of hand, arguing that the withdrawal which the Saudi proposal demanded — every inch of territory, back to the borders before the Six-Day War — would be not only politically unacceptable, but practically impossible. In the final days of the Camp David summit, as our failure was becoming inescapably clear, a disheartened Bill Clinton said to me that he could understand, just about, why Yasir Arafat had not accepted the unprecedentedly far-reaching proposals I had presented. But what he couldn’t grasp was how the Palestinian leader could say no even to accepting them as a basis for the hard, further work which we all knew a final peace agreement would entail. Wasn’t Arafat capable of looking beyond the political risks, of understanding the greater risks of inaction. Of seeing the rewards? Of looking ahead? 13 HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_011484

Page 14 - HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_011485

My fear — not just on issues like the Saudi peace plan, but in charting our place in a dramatically changed world, and safeguarding our twin Jewish and democratic identities at home, pairing our physical strength with an equally strong moral centre — is that we Israelis are now in danger of jettisoning the example of David Ben-Gurion. For Yasir Arafat’s. 14 HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_011485

Page 15 - HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_011486

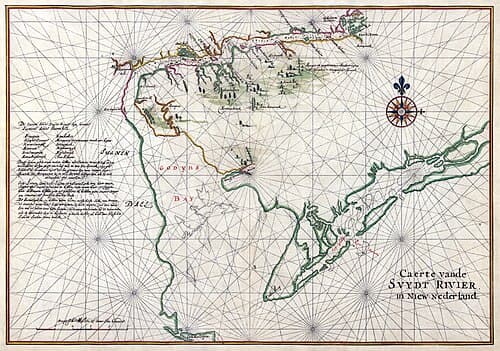

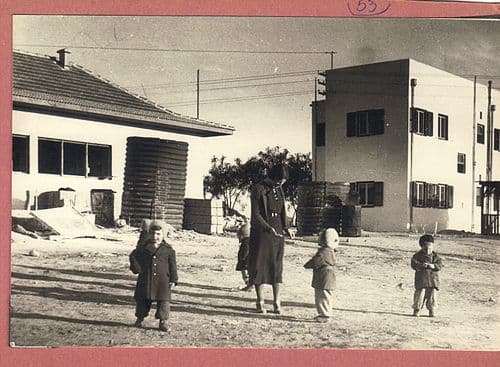

Chapter One I am an Israeli, but also a Palestinian. I was born in February 1942 in British- ruled Palestine on a fledgling kibbutz: a cluster of wood-and-tarpaper huts amid a few orange groves and vegetable fields and chicken coops. It was just across the road from an Arab village named Wadi Khawaret, which disappeared, with the establishment of the State of Israel, when I was six years old. As Prime Minister half-a-century later, during my stubborn yet ultimately fruitless drive to secure a final peace treaty with Yasir Arafat, there were media suggestions that my childhood years gave me a personal understanding of the pasts of both our peoples, Jews and Arabs, in the land which each of us saw as our own. But that is in some ways misleading. Yes, I did know first-hand that we were not alone in our ancestral homeland. At no point in my childhood was I ever taught to hate the Arabs. I never did, even when, in my years defending the security of Israel, I had to fight, and defeat, them. But my conviction that they, too, needed the opportunity to establish a state came only later, after my many years in uniform, and especially when, as deputy chief-of-staff under Yitzhak Rabin, we were faced with the explosion of violence in the West Bank and Gaza that became known as the first intifada. And while my determination as Prime Minister to find a negotiated resolution to our conflict was in part based on a recognition of the Palestinian Arabs’ national aspirations, the main impulse was my belief that such a compromise was profoundly in the interest of Israel: the Jewish state whose birth I witnessed, whose existence I had spent decades defending on the battlefield and which I was ultimately elected to lead. Zionism, the political platform for the establishment of a Jewish state, emerged in the late 1800s in response to a brutal reality. And that, too, was a part of my own family’s story. Most of the world’s Jews, who lived in the Russian empire and Poland, were trapped at the time in a vise of poverty, powerlessness and anti-Semitic violence. Even in the democracies of Western Europe, Jews were not necessarily secure. Theodor Herzl, a thoroughly assimilated Jew in Vienna, published the foundation text of Zionism in 1896. It was called Der Judenstaat. “Jews have sincerely tried everywhere to merge with the national communities in which we live, seeking only to preserve the faith of our fathers,” he wrote. “In vain are we loyal patriots, sometimes super- loyal. In vain do we make the same sacrifices of life and property as our fellow citizens... In our native lands where we have lived for centuries, we are still decried as aliens.” Zionism’s answer was the establishment of a state of our 15 HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_011486

Sponsored

Page 16 - HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_011487

own, in which we could achieve the self-determination and security denied to us elsewhere. During the 1890s and the early years of the new century, more than a million Jews fled Eastern Europe, but mostly for America. It was only in the 1920s and 1930s that significant numbers arrived in Palestine. Then, within a few years, Hitler rose to power in Germany. The Jews of Europe faced not just discrimination or pogroms. They were systematically, industrially, murdered. From 1939 until early 1942 when I was born, nearly two million Jews were killed. Six million would die by the end of the war. Almost the whole world, including the United States, rejected pleas to provide a haven for those who might have been saved. Even after Hitler was defeated, the British shut the doors of Palestine to those who had somehow survived. I was three when the Holocaust ended, and it was three years later that Israel was established in May 1948, and neighboring Arab states sent in their armies to try to snuff the state out in its infancy. It would, again, be some years before I fully realized that this first Arab-Israeli war was the start of an essential tension in my country’s life, and my own: between the Jewish ethical ideals at the core of Zionism and the reality of our having to fight, and sometimes even kill, in order to secure, establish and safeguard our state. Yet even as a small child, I was keenly aware of the historic events swirling around me. Mishmar Hasharon, the hamlet north of Tel Aviv where I spent the first 17 years of my life, was one of the early kibbutzim. These collective farming settlements had their roots in Herzl’s view that an avant-garde of “pioneers” would need to settle a homeland that was still economically undeveloped, and where even farming was difficult. Members of Jewish youth groups from Eastern Europe, among them my mother, provided most of the pioneers, drawing inspiration not just from Zionism but by the still untainted collectivist ideals represented by the triumph of Communism over the czars in Russia. It is hard for people who didn’t live through that time to understand the mindset of the kibbutzniks. They had higher aspirations than simply planting the seeds of a future state. They wanted to be part of transforming what it meant to be a Jew. The act of first taming, and then farming, the soil of Palestine was not 16 HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_011487

Page 17 - HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_011488

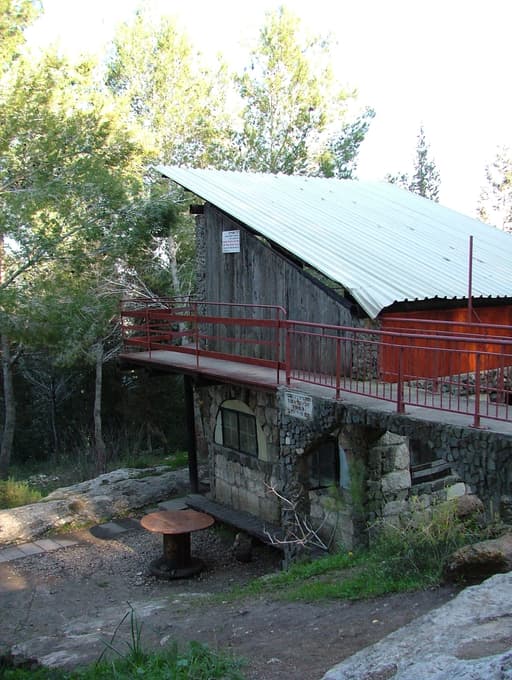

just an economic imperative. It was seen as deeply symbolic, signifying Jews finally taking control of their own destiny. It was a message that took on an even greater power and poignancy after the mass murder of the Jews of Europe during the Holocaust. Even for many Israelis nowadays, the all-consuming collectivism of life on an early kibbutz, and the physical challenges, are hard to imagine. Among the few dozen families in Mishmar Hasharon when I was born, there was no private property. Everything was communally owned and allocated. Every penny — or Israeli pound — earned from what we produced went into a communal kitty, from which each one of the 150-or-so families in Mishmar Hasharon when I was a child got a small weekly allowance. By “small”, I mean tiny. For my parents and others, even the idea of an ice cream cone for their children was a matter of keen financial planning. More often, they would save each weekly pittance with the aim of pooling them at birthday time, where they might stretch to the price of a picture book, or a small toy. Decisions on any issue of importance were taken at the aseifa, the weekly meeting of kibbutz members held on Saturday nights in our dining hall. The agenda would be tacked up on the wall the day before, and the session would usually focus on one issue, ranging from major items like the kibbutz’s finances to the question, for instance, of whether our small platoon of delivery drivers should be given pocket money to buy a sandwich or a coffee on their days outside the kibbutz or be limited to wrapping up bits of the modest fare on offer at breakfast time. That debate ended in a classic compromise: a bit of money, but very little, so as to avoid violating the egalitarian ethos of the kibbutz. But perhaps the aspect of life on the kibbutz most difficult for outsiders to understand, especially nowadays, is that we children were raised collectively. We lived in dormitories, organized by age-group and overseen by a caregiver: in Hebrew, a metapelet, usually a woman in her 20s or 30s. For a few hours each afternoon and on the Jewish Sabbath, we were with our parents. But otherwise, we lived and learned in a world consisting almost entirely of other children. Everything around us was geared towards making us feel like a band of brothers and sisters, and as part of the guiding spirit of the kibbutz. Until our teenage years, we weren’t even graded in school. And though we didn’t actually study how to till the land, some of my fondest early memories are of our “children’s farm” — the vegetables we grew, the cows we milked, the hens and chickens that gave us our first experience of how life was created. And the 17 HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_011488

Page 18 - HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_011489

aroma always wafting from the stone ovens in the bakery at the heart of the kibbutz, where we could see the bare-chested young men producing loaf after loaf of bread, not just for Mishmar Hasharon but villages and towns for miles around us. Until our teenage years, we lived in narrow, oblong homes, four of us to a room, unfurnished except for our beds, under which we placed our pair of shoes or sandals. At one end of the corridor was a set of shelves where we collected a clean set of underwear, pants and socks each week. At the other end were the toilets — at that point, the only indoor toilets on the kibbutz, with real toilet- seats, rather than just holes in the ground. All of us showered together until the age of twelve. I can’t think of a single one of us who went on to marry someone from our own age-group in the kibbutz. It would have seemed almost incestuous. Mishmar Hasharon and other kibbutzim have long since abandoned the practice of collective child-rearing. Some in my generation look back on the way we were raised not only with regret, but pain: a sense of parental absence, abandonment or neglect. My own memories, and those of most of the children I grew up with, are more positive. The irony is that we probably spent more waking time with our parents than town or city children whose mothers and fathers worked nine-to-five jobs. The difference came at bedtime, or during the night. If you woke up unsettled, or ill, the only immediate prospect of comfort was from the metapeled, or another of the kibbutz grown-ups who might be on overnight duty. Still, my childhood memories are overwhelmingly of feeling happy, safe, protected. I do remember waking up once, late on a stormy winter night when I was nine, in the grips of a terrible fever. I’d begun to hallucinate. I got to my feet and, without the thought of looking anywhere else for help, made my wobbly way through the rain to my parents’ room and fell into their bed. They hugged me. They dabbed my forehead with water. The next morning, my father wrapped me in a blanket and took me back to the children’s home. To the extent that I was aware my childhood was different, I was given to understand it was special, that we were the beating heart of a Jewish state about to be born. I once asked my mother why other children got to live in their own apartments in places like Tel Aviv. “They are ironim,” she said. City-dwellers. Her tone made it clear they were to be viewed as a slightly lesser species. 18 HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_011489

Sponsored

Page 19 - HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_011490

Though both my parents were part of the pioneer generation, my mother, unlike my father, actually arrived as a pioneer, part of a Jewish youth group from Poland that came directly to the kibbutz. In addition to being more naturally outgoing than my father, she came to see Mishmar Hasharon has her extended family and spent every one of her one hundred years there. Esther Godin, as the then was, grew up in Warsaw. Born in 1913, she was the oldest of the six children of Samuel and Rachel Godin. Poland at the time was home to the largest Jewish community in the world, more than 3 million by the time of the Holocaust. While the Jews of Poland had a long history, the Godins did not. Before the First World War, my mother’s parents made their way from Smolensk in Russia to Warsaw, which was also under czarist rule. When the war was over, the Bolshevik Revolution had toppled the czars. Poland became independent, under the nationalist general Josef Pilsuldski. The Godins had a decision to make: either return to now-Communist Russia or stay in the new Polish state, though without citizenship because they had not been born there. No doubt finding comfort, community and a sense of safety amid the hundreds of thousands of Jews in the Polish capital, they chose Pilsuldski over Lenin. They lived in what would become the Warsaw Ghetto, on Nalewski Street, where Samuel Godin eked out a living as a bookbinder. My mother came to Zionism as a teenager, and it was easy to understand why she, like so many of the other young Jews around her, was drawn to it. She saw how hard her parents were struggling economically, on the refugee fringes of a Jewish community itself precariously placed in a newly assertive Poland. She saw no future for herself there. Though she attended a normal state-run high school, she and her closest friends joined a Zionist youth group called Gordonia, which had been founded in Poland barely a decade earlier. She started studying Hebrew. Each summer, from the age of 13, she and her Gordonia friends would spend deep in the Carpathian Mountains. They worked for local Polish landowners, learning the rudiments of how to farm and the rigors of simple physical labor. Late into the evening, they would learn not just about agriculture but Jewish history, the land of Palestine, and how they hoped to put both their new-found skills and the Zionist ideals into practice. She had just turned 22 when she set off for Mishmar Hasharon with 60 other Gordonia pioneers in the summer of 1935. It took them nearly a week to get there. They travelled by train south through Poland, passing not far from the little town of OSwiecim which would later become infamous as the site of the Auschwitz concentration camp. Then, on through Hungary and across Romania 19 HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_011490

Page 20 - HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_011491

to the grand old Black Sea port of Constanta, and by ship through the Bosphorus, past Istanbul, and on to Haifa on the Palestinian coast, from where they were taken by truck to their bunk-bed rooms in one of a dozen prefab structures on the recently established kibbutz. Though the water came from a well, and it lacked even the basic creature comforts of the cramped Godin apartment in Warsaw, that, to my mother, was just part of the challenge, and the dream, she’d embraced and had come to define her. I know that she felt, on arriving in the kibbutz, that only now was her life truly beginning. It was a feeling that never left her. Yet it was always clouded by the memory of the family she left behind. When the Second World War began in September 1939, the Germans, and then the Soviets, invaded, overran and divided Poland. Two of my mother’s three sisters fled to Moscow. Her teenage brother Avraham went underground, joining the anti-Nazi partisans. All three would survive the war. Yet in the autumn of 1940, the rest of her family found themselves inside the Warsaw Ghetto with the city’s other 400,000 Jews. My mother’s parents died there, along with her 13-year-old brother Itzik and her little sister Henya, who was only 11. When my mother arrived in the kibbutz, her Gordonia friends assumed she would marry a young man named Ya’akov Margalit, the leader of their group back in Warsaw. But the budding romance fell victim to the Zionist cause. As she was embarking on her new life, he was frequently back in Poland training and arranging papers for further groups of pioneers. He continued to write her long, heartfelt letters. But the letters had to be brought from the central post office in Tel Aviv, and the kibbutznik who fetched the mail was a quiet, dimunitive 25-year-old named Yisrael Mendel Brog — my father. Known as Srulik, his Yiddish nickname, he had come to Palestine five years earlier. He was an ordinary kibbutz worker. He drove a tractor. My father’s initial impulse in coming to Palestine was more personal than political. He was born, in 1910, in the Jewish shtet/ of Pushelat in Lithuania, near the larger Jewish town of Ponovezh, a major seat of rabbinic learning and teaching. His own father, though the only member of the Pushelat community with rabbinical training, made his living as the village pharmacist. Many of the roughly 10,000 Jews who lived there had left for America in the great exodus from Russian and Polish lands at the end of the 19" century. By the time my father was born, the community had shrunk to only about 1,000. When he was two years old, a fire broke out, destroying dozens of homes, as well as the shtetl’s only synagogue. Donations soon arrived from the US, and my paternal 20 HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_011491

Page 21 - HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_011492

grandfather was put in charge of holding the money until rebuilding plans were worked out. The problem was that word spread quickly about the rebuilding fund. On the night of September 16, 1912, two burglars burst into my grandfather’s home and stole the money. They beat him and my grandmother to death with an axle wrenched loose from a nearby carriage. Their four-year-old son Meir — my father’s older brother — suffered a deep wound from where the attackers drove the metal shaft into his head. He carried a golf-ball-sized indentation in his forehead for the rest of his life. My father had burrowed into a corner, and the attackers didn’t see him. The two orphaned boys were raised by their paternal grandmother, Itzila. Yet any return to normalcy they may have experienced was cut short by the outbreak of the First World War, forcing her to flee with them by train ahead of the advancing German army. They ended up some 1,500 miles south, in the Crimean city of Simferopol. Initially under czarist rule, then the Bolsheviks and from late 1917 until the end of the war under the Germans, they had to deal with cold, damp and a chronic shortage of food. My Uncle Meir quickly learned how to survive. He later told me that he would run after German supply carriages and collect the odd potato that fell off the back. Realizing that the German soldiers had been wrenched from their own families by the war, he began taking my father with him on weekends to the neighborhood near their barracks, where the soldiers would sometimes give them cookies, or even a loaf of bread. Yet they were deprived of the basic ingredients of a healthy childhood: nutritious food and a warm, dry room in which to sleep. By the time Itzila brought them back to settle in Ponovezh at the end of the war, my father was diagnosed with the bone-development disease, rickets, caused by the lack of Vitamin D in their diet. In another way, however, my father was the more fortunate of the boys. The lost schooling of those wartime years came at a less formative time for him than for his brother. Meir never fully made up the lost ground in school. My father simply began his Jewish primary education, cheder, a couple of years later than usual. He thrived there. Still, when it was time for him to enter secondary education, he decided against going on with his religious education. Meir was preparing to leave for Palestine, so my father enrolled in the Hebrew-language, Zionist high school. When he graduated, one of the many Brog relatives who were by now living in the United States, his Uncle Jacob, tried to persuade him to come to Pittsburgh for university studies. But with Meir signing on as his sponsor with the British Mandate authorities, he left for Palestine shortly before 21 HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_011492

Sponsored

Page 22 - HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_011493

his twentieth birthday. Jacob did still insist on helping financially, which allowed my father to enroll at the Hebrew University in Jerusalem. He did well in his studies — literature, history and philosophy — but abandoned them after two years. His explanation for not staying on, when I asked him years later, was that with the accelerating activity of the Zionist pioneers, it felt wrong to him to spend his days going to lectures, reading books and writing essays. I am sure that he also felt isolated and alone, with Meir, the only link to his life before Palestine, working in Haifa on the coast, four or five hours by bus from Jerusalem. When he began looking for a way to become part of the changes going on around him, Mishmar Hasharon didn’t yet exist. Its founding core — a dozen Russian Jewish pioneers — was still working on argicultural settlements near Herzliya, north of Tel Aviv, until they found a place to start their kibbutz. But they had been joined by several young men and women who, though a year or two older than my father, had been with him at the Hebrew High School in Ponovezh. He decided to join them. Late in 1932, the Jewish National Fund, supported financially by leading Jewish figures in western Europe and the US, bought 2,000 acres from an Arab landowner near Wadi Khawaret. The area was set aside for three Jewish settlements: a moshav called Kfar Haim, where the land was divided into family plots, and two kibbutzim. One was called Ma’abarot. Next to it was Mishmar Hasharon. My father was among the seventy youngsters who set off in three trucks with everything they figured they would need to turn the hard, scrubby hill into a kibbutz. They built the core from pre-fab kits: wooden huts to sleep in and a slightly larger one for the dining hall. They dug a well and ordered a pump from Tel Aviv, at first for drinking and washing, but soon allowing them to begin a vegetable garden, a dairy with a dozen cows, a chicken coop with a few hundred hens, and to plant a first orange grove and a small vineyard. Still, by the time my mother arrived three years later, there were not enough citrus trees, vines, cattle and chickens to occupy a membership which now numbered more than 200. Along with some of the others, my father worked outside the kibbutz, earning a regular paycheck to help support the collective. On his way back, he would stop at the post office in Tel Aviv to pick up letters and packages for the rest of the kibbutz — including Ya’akov Margalit’s love letters to my mother. That was how my parents’ friendship began, how a friendly hello led to shared conversation at the end of my father’s working day, and how, a few years later, my mother decided to spurn her Gordonia suitor in favor of Srulik Brog, the postman. It was not until 1939 that they moved in 22 HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_011493

Page 23 - HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_011494

together. They didn’t bother getting married until the summer of 1941. Perhaps because this was less than nine months before I was born, my mother always remained vague when asked their exact wedding date. My parents were an unlikely pair. My mother — bright, lively and energetic — was a doer, who believed passionately in the grand social experiment of kibbutz life. Having helped her mother raise her siblings in Warsaw, and with a natural affinity from children, she became the main authority on issues related to childbirth and early childcare. She actively partook in the kibbutz’s planning and politics, and reveled in its social life. My father was more detached both politically and socially. He was more contemplative, less assertive, less self- confident. Though he agreed broadly with the founding principles of the kibbutz, and wanted to play his role in making it a success, I could see, as I grew older, that he was often impatient at what he saw as its intellectual insularity and its ideological rigidities. Though it didn’t strike me at the time, he was not a large man. As a result of his childhood illness, he never grew to more than five-foot-four. Still, he was a powerful presence, stocky and strong from his work on the kibbutz. He had a deep, resonant voice and wise-looking, blue-gray eyes. It was only through Uncle Meir that by the time I was born, he had moved on from driving a tractor to a more influential role on the kibbutz. Meir worked for the Palestine Electric Company and when Mishmar Hasharon installed its own electricity system, the PEC was in charge of the work. Meir trained my father and put him forward as the kibbutz contact for maintaining and repairing the equipment. He was well suited for the work. He was a natural tinkerer, a problem-solver. He was good with his hands, and his natural caution was an additional asset as the kibbutz got to grips with the potential, and the potential dangers, of electric power. Once the system was installed, he became responsible for managing any aspect of the settlement that involved electricity: water pumps, the irrigation system, the communal laundry and our bakery. My parents were courteous and polite with each other, but they never showed any physical affection in our presence. None of the adults did. This was part of an unspoken kibbutz code. Not only for kibbutzniks, but for all the early Zionists, outward displays of emotion were seen as a kind of selfishness that risked undermining communal cohesion, tenacity and strength. Because I’d known no other way, this did not strike me as odd. Besides, I was a quiet, contemplative, bookish and self-contained child. Only in later years did I come to see the lasting effect on me. It was be a long time before I became comfortable 23 HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_011494

Page 24 - HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_011495

showing my feelings, beyond my immediate family and a few close friends. When I was in the army, this wasn’t an issue. Self-control, especially in high- pressure situations, was a highly valued asset. But in politics, I think that it did for a considerable time inhibit my ability to connect with the public, or at least with the news media that played such a critical intermediary role. And it caused me to be seen not just as reserved or aloof, but sometimes as cold, or arrogant. I did get much that I value from my parents. From my mother, her boundless energy, activism, her attention to detail, and her focus on causes larger than herself — her belief that politics mattered. Also her love for art and literature. When I would come home from the children’s dormitory to my parents’ room — just nine feet by ten, with a wooden trundle bed to save space during the day — there was always a novel or a book of verse sharing the small table with my parents’ most single prized possession: their kibbutz-issue radio. As achild, however, I spent much more time with my father. He was my guide, my protector and role model. Like my mother, he never mentioned the trials which they and their families endured before arriving in Palestine. Nor did they ever speak to me in any detail about the Holocaust. No one on the kibbutz did. It was as if the memories were scabs they dared not pick at. Also, it seemed, because they were determined to avoid somehow passing on these remembered sadnesses to their sons and daughters. Still, when I was ten or eleven, my father did — once, inadvertently — open a window on his childhood. Every Saturday morning, we would listen to a classical music concert on my parents’ radio. One day, as the beautiful melodies of Tchaikovsky’s violin concerto in D came through the radio, I was struck by the almost trancelike look that came over my father’s face. He seemed to be in another, faraway, place. When the music ended, he turned and told me about the first time he’d heard it. It was on the train ride into Crimean exile with Itzila and Meir in the early days of the First World War. The train took five days to reach the Crimea and sometimes halted for hours at a time. Every evening, a man at the far end of their carriage would take out his violin and play the second movement of the Tchaikovsky concerto. I have heard the piece in concert halls many times since. When the orchestra begins the second movement — with the violin notes climbing higher, trembling ever so subtly — it sends a shiver down my spine. I can’t help thinking of the railway car in which my then four-year-old father and other Jews from Ponovezh escaped the Great War of 1914. And of other trains, in another war 25 years later, carrying Jews not to safety but to death camps. 24 HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_011495

Sponsored

Page 25 - HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_011496

Listening to the concert program in my parents’ room was something I always looked forward to. It was my father who encouraged me, when I was eight, to begin learning to play the piano. I took lessons once a week all during my childhood along with several other of the kibbutz children. When we got old enough, we took turns playing a short piece — the secular, kibbutz equivalent of an opening prayer — at the Friday-night meal in the dining hall. I have always cherished being able to play. Sitting down at the piano and immersing myself in Tchaikovsky, Beethoven, Schubert or Mozart never ceases to bring me a sense of calm, freedom and, especially nowadays, when I have finally worked to master a particularly intricate piece, a feeling of pure joy. As a young child, I spent most of my waking hours in the company of my several dozen kibbutz “siblings” in the children’s home, the dining hall, or running through the open spaces in the center of the kibbutz with our metapelet. She would often take us through the orange groves in the afternoon, and sometimes across the main road to the Arab village. Wadi Khawaret consisted of a few dozen concrete homes built back from a main street bordered by shops and storehouses. She would buy us sweets in the little grocery store. The man behind the counter had a kindly, weathered face and a dark moustache. Dressed in a gray galabiya and a keffiyeh, he smiled when we came in. There was always a group of Palestinian women, in full- length robes, seated on stoops outside breastfeeding their babies. We saw cattle, bulls, even the odd buffalo, being led to or from the fields. I sensed no hostility, and certainly no hatred, toward us in the village. The people seemed warm, and benignly indifferent to the dozen Jewish toddlers and their metapelet. My own attitude to Wadi Khawaret was of benign curiosity. I did not imagine that within a couple of years we would be on opposite sides of a war. I enjoyed these visits, as I enjoyed every part of my early childhood. Each age-group on the kibbutz was given a name. Ours was called dror. It was the Hebrew word for “freedom”. But dror was also the name of one of the Jewish youth movements in the Warsaw Ghetto, heroes in their doomed uprising against the Nazis. Little by little, from about the age of five, I became more aware of the suffering the Jews had so recently endured in the lands my parents had left behind, the growing 25 HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_011496

Page 26 - HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_011497

tension around us and the sense that something momentous was about to happen as the prospect of a state got closer. The memories remain with me to this day, like a series of snapshots. It was on a spring morning in 1947 that I got my first real sense that the Jewish state was something which would have be fought for, and that youngsters not all that much older than me would have a critical role to play. I got a close-up look at the elite of the Zionist militias, the Palmach. It numbered something like 6,000, from a pre-state force totaling around 40,000. The Palmachniks were highly motivated, young political activists. They had no fixed base. Each platoon, almost all of them teenagers, spent five or six months at a time on various kibbutzim. For the first two weeks of each month, they would earn their keep by working in the fields. They spent the other weeks training. I had just turned five when I watched three dozen Palmach boys and girls, in their T-shirts and short khaki pants, rappel confidently down the side of one of our few concrete buildings. The building was only 25 or 30 feet high, but it looked like a skyscraper from my perch on the grass in front, and the feat of the young Palmachniks seemed to me nothing short of heroic. A few months later, on a Saturday afternoon in November 1947, I crowded into my parents’ room as the Haganah radio station crackled out its account of a United Nations debate on the future of Palestine. The session was the outcome of a long train of events starting with Britain’s acknowledgement that its mandate to rule over Palestine was unsustainable. The British had proposed a series of arrangements to accommodate both Arab and Jewish aspirations. Now, the UN was meeting to consider the idea of splitting Palestine into two new states, one Arab and the other Jewish. Since the partition was based on existing areas of Arab and Jewish settlement, the proposed Jewish state looked like a boomerang, with a long, very narrow center strip along the Mediterranean, broadening slightly into the Galilee in the north and the arid coastline in the south. Jerusalem, the site of the ancient Jewish temple, was not part of it. It was to be placed under international rule. By no means all Zionist leaders were happy with partition. Many, on both the political right and the left, wanted a Jewish state in all of Palestine, with Jerusalem as its centerpiece. But Ben-Gurion and the pragmatic mainstream argued that UN endorsement of a Jewish state — no matter what its borders, even with a new Palestinian Arab state alongside it — would represent a historic achievement. The proceedings went on for hours. At sundown, we had to return to the children’s home. But we were woken before dawn. The vote for partition 26 HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_011497

Page 27 - HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_011498

— for the Jewish state Herzl had first dreamed of 50 years before — had been won. A huge bonfire blazed in front of the bakery. All around us the grown-ups were singing and dancing in celebration. On the Arab side, there was no rejoicing. Every one of the Arab delegations at the UN voted against partition, rejecting a Jewish state even if it was created along with a Palestinian Arab one. Violence erupted the next day. An attack on a bus near Lydda, near the road up to Jerusalem, left six Jews dead. Similar attacks occurred around the country. Shooting broke out in mixed Arab-and- Jewish towns and cities: Jaffa on the southern edge of Tel Aviv. Safed, Tiberias and Haifa in the north, and in Jerusalem. I followed all this with curiosity and trepidation through my halting attempts to read Davar le Yeladim, the weekly children’s edition of the Labour Zionist newspaper Davar. We children felt an additional connection with what was going on. One of our Dror housemates, a boy named Giora Ros, had left the year before when his father took a job in Jerusalem. As the battle for the city raged through the end of 1947 and into 1948, its besieged Jewish residents fought for their lives. We sent our friend packages of clothing and food, which we saved up by eating only half of an egg at breakfast and smaller portions at dinner. The mood darkened further at the end of January 1948, four months before the British departed. A cluster of settlements known as Gush Etzion, south of Jerusalem near the hills of Bethlehem, also came under siege. Around midnight on January 15, a unit of Haganah youngsters set off on foot to try to break through. They became known as “The 35”. Marching through the night from Jerusalem, they had made it only within a couple of miles of Gush Etzion when they were surrounded and attacked by local Arabs. By late afternoon, all of them were dead. When the British authorities recovered their bodies, they found that the enemy had not simply killed them. All of the bodies had been battered and broken. Rumors spread that in some cases, the dead men’s genitals had been cut off and shoved into their mouths. Since I was still a few weeks short of my sixth birthday, I was spared that particular detail. But not the sense of horror over what had happened, nor the central message: the lengths and depths to which the Arabs of Palestine seemed ready to go in their fight against us. “Hit’alelu bagufot!” was the only slightly sanitized account we children were given. “They mutilated the corpses!” Even after the partition vote, statehood was not a given. In the weeks before the British left, two senior Americans —the ambassador to the UN and Secretary 27 HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_011498

Sponsored

Page 28 - HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_011499

of State George C. Marshall — recommended abandoning or at least delaying the declaration of an Israeli state. Yet Ben-Gurion feared that any delay risked the end of any early hope of statehood. After he managed to secure a one-vote majority in his de facto cabinet, the state was declared on May 14, 1948. And hours later, the armies of five Arab states crossed into Palestine. 28 HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_011499

Page 29 - HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_011500

Chapter Two The 1948 war and the decade that followed remain vivid in my mind not just for the obvious reason: they secured the survival of the infant state of Israel and saw it into a more assured and independent young adulthood. It was also the time when I grew from a young child —introspective and contemplative, aware of how quickly my mind seemed to grasp numbers and geometric shapes and musical notes, but also small for my age and awkward at the sports we’d play on the dusty field at the far edge of the kibbutz — into a sense of my own place in the family and community and the country around me. I did, along the way, become arguably the most effective left defensive back on our kibbutz soccer team. But that was not because I suddenly discovered a buried talent for the game. Physically, I was like my father. I had natural hand coordination which made delicate tasks come easily — one reason I would soon discover a pastime that lent itself to acts of kibbutz mischief bordering on juvenile delinquency. But when it came to larger muscles, I was hapless, if not hopeless. My prowess as a soccer defenseman was because no opposing player in his right mind, once I’d inadvertently cut his knees from under him when aiming for the ball, felt it was worth coming anywhere close to me. But when the war broke out in earnest in the spring of 1948, my focus, like that of all Israelis, was on the fighting, which even the youngest of us knew would determine whether the state would survive at all. Day after day, my father helped me to chart each major advance and setback on a little map. Dozens of kibbutzim around the country were in the line of fire. Some had soon fallen, while others were barely managing to hang on. Just five miles inland from us, an Israeli settlement came under attack by an Iraqi force in the nearby Arab village of Qaqun. But inside Mishmar Hasharon, I had the almost surreal feeling that this great historical drama was something happening everywhere else but on our kibbutz. If it hadn’t been for the radio, or the newsreels which we saw in weekly movie nights in the dining hall, and the little map on which I traced its course with my father, I would barely have known a war was going on. One Arab army did get near to us: the Iraqis, in Qaqun. If they had advanced a few miles further, they could have overrun Mishmar Hasharon, reached the coast and cut the new Jewish state in half. I can still remember the rumble of what sounded like thunder one morning in June 1948, as the Alexandronis, one of the twelve brigades in the new Israeli army, launched their decisive attack on the Iraqis. 29 HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_011500

Page 30 - HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_011501

“No reason to be afraid,” our metapelet kept telling me. That only made me more scared. Yet within a few hours, everything was quiet again, and never again did the shellfire get near to us. A few weeks later, I heard the only gunfire inside the kibbutz itself. It came from the top of our water tower. The man on guard duty thought he saw movement on the road outside. But it turned out to be nothing. It wasn’t until well into 1949 that formal agreements were signed and “armistice line” borders drawn with the Arab states. By the measure that mattered most — survival — Israel had won and the Arab attackers had lost. Jordan did end up in control of the West Bank, as well as the eastern half of a divided city of Jerusalem, including the walled Old City and the site of the ancient Jewish temple. The new Israel remained, at least geographically, vulnerable. It was just 11 miles wide around Tel Aviv and even narrower, barely half that, near Mishmar Hasharon. Egyptian-held Gaza was seven miles from the southern Israeli city of Ashkelon and just 40 from the outskirts of Tel AVIV. Israel did secure control of the entire Galilee, up to the pre-war borders with Lebanon and Syria, and of the Negev Desert in the south. The territory of our new state was about a third larger than the area proposed under the UN partition plan rejected by the Arabs. Yet the victory came at a heavy price: more than 6,000 dead, one per cent of the Jewish population of Palestine at the time. It was as if America had lost two million in the Vietnam War. One-third of the Israeli dead were Holocaust survivors. The Arabs paid a heavy price too, and not just the roughly 7,000 people who lost their lives. Nearly 700,000 Palestinian Arabs had fled — or, in some cases, been forced to flee — towns and villages in what was now Israel. The full extent and circumstances of the Arabs’ flight became known to us at Mishmar Hasharon only later. But it did not take long to notice the change around us. Wadi Khawaret was physically still there, but all of the villagers were gone. As far as I could discover, none had been killed. They left with a first wave of refugees in April 1948, and eventually ended up near Tulkarem on the West Bank. After the war, the Israeli government divided up their farmland among nearby kibbutzim including Mishmar Hasharon. The absence of our former neighbors in Wadi Khawaret seemed to me at the time simply a part of the war. From the moment the violence started, I understood there would be suffering on both sides. When we sent our care packages to Giora Ros in Jerusalem, I remember trying to imagine what “living 30 HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_011501

Sponsored

Page 31 - HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_011502

under siege” would feel like, and what would happen to Giora if it succeeded. Especially after the murder and the mutilation of The 35, I assumed the war would come down to a simple calculus. If there was going to be an Israel — if there was going to be a Mishmar Hasharon — we had to win and the Arabs had to lose. At first, even the fact our kibbutz had been given a share of the land of Wadi Khawaret seemed just another product of the war. After all, Ben-Gurion had accepted the plan for two states. The Arabs had said no, deciding to attack us instead. Someone had to farm the land. Why not us? Yet events after the war did lead me to begin to ask myself questions of basic fairness, and whether we were being faithful to some of the high-sounding ideals I heard spoken about with such pride on the kibbutz. The Palestinians were not the only refugees. More than 600,000 Jews fled into Israel from Arab countries where they had lived for generations. More than 100,000 arrived from Iraq, and several hundred thousand from Morocco, Tunisia and Algeria in north Africa. Immediately after the war, about 50,000 were airlifted out of Yemen, where they had endured violent attacks ever since the UN partition vote. The reality that greeted the Yemenis in Israel was more complex. Most were initially settled in tented transit camps. I’m not sure how several dozen Yemeni families made their way to Wadi Khawaret, but it made sense for them to move into the village’s vacant homes. It was empty except for several deserted buildings which we and other kibbutzim began using for storage and, later, for our transport co-operative. Yet a few nights after the Yemenis moved in, a posse of young men, including some from Mishmar Hasharon, descended on them and, armed with clubs and wooden staves, drove them away. I was shocked. I’d seen the photos in Davar le Yeladim celebrating the airlift, with the Yemenis kissing the airport tarmac in relief, gratitude and joy at finding refuge in the new Israeli state. Now, for the “crime” of moving into a row of empty buildings in search of a decent place to live, they’d been beaten up and chased away. By us. I realized Wadi Khawaret no longer belonged to the Arabs. But, surely, our kibbutz had no more right to the buildings than Jews who had fled from Yemen and needed them a lot more than we did. For days, I tried to discover who had joined the vigilante attack. Though everyone seemed to know what had happened, no one talked about it. In the dining hall, I ran my 31 HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_011502