HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_012747 - HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_012897

Evilicious

Document HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_012747 is a government record from the House Oversight Committee, consisting of 151 pages, and appears to be related to the subject of 'Evilicious'.

This document includes front matter from a book titled 'Evilicious' by Marc D. Hauser. The book seems to explore the causes of evil, drawing on historical events such as the Holocaust and the dictatorships of Milton Obote and Idi Amin in Uganda. The author also touches on the capacity for human kindness, contrasting it with the horrors of evil.

Key Highlights

- •The document is from the House Oversight Committee.

- •The document includes front matter from Marc D. Hauser's book 'Evilicious'.

- •The book explores the causes of evil, referencing historical events and personal experiences.

- •Mentions both the horrors of evil and the capacity for human kindness.

Frequently Asked Questions

Books for Further Reading

Perversion of Justice: The Jeffrey Epstein Story

Julie K. Brown

Investigative journalism that broke the Epstein case open

Filthy Rich: The Jeffrey Epstein Story

James Patterson

Bestselling account of Epstein's crimes and network

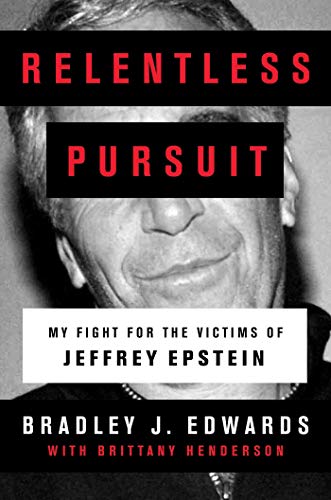

Relentless Pursuit: My Fight for the Victims of Jeffrey Epstein

Bradley J. Edwards

Victims' attorney's firsthand account

Document Information

Bates Range

HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_012747 - HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_012897

Pages

151

Source

House Oversight Committee

Original Filename

Evilicious.pdf

File Size

1.50 MB

Document Content

Page 1 - HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_012747

es | o o Explaining our taste for excessive harm Marc D. Hauser Viking/Penguin HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_012747

Page 2 - HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_012748

For Jacques and Bert Hauser, my parents, my friends, and my reminder that life should be lived to its fullest Hauser Evilicious. Front matter 2 HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_012748

Page 3 - HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_012749

Pleasure is the greatest incentive to evil. — Plato To witness suffering does one good, to inflict it even more so. — Friedrich Nietzsche Man produces evil as a bee produces honey. — William Golding Hauser Evilicious. Front matter HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_012749

Sponsored

Page 4 - HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_012750

Dear reader, Having lived in Uganda and spoken with people who escaped from the savagery of the brutal dictators Milton Obote and Idi Amin, having heard stories of my father’s childhood as a Jew running through Nazi occupied France, and reading past and present-day accounts of genocide, I am familiar with the horrors of evil. I have also been a student of human nature, trained as a scientist. These experiences have propelled me to study the causes of evil, attempt to make some progress in explaining it to myself, and hopefully to you. There is a great urgency to understanding this problem. None of us can afford to passively watch millions of individuals lose their homes, children, and lives as a result of malice. Sloth is asin, especially when we live in a world where cultures of evil can so easily erupt. Tam also familiar with and deeply moved by human kindness, our capacity to reach out and help strangers. When my father was in a boarding school in the south of France, hiding from the Nazis, a little girl approached him and asked if he was Jewish. My father, conditioned by his parents to deny his background, said no. The girl, sensing doubt, said “Well, if you are Jewish, you should know that the director of the school is handing Jewish children over to the Nazis.” My father promptly called his parents who picked him up, moved him to another village and school, and survived to tell the story. This little girl expressed one of our species’ signature capacities: the ability to show compassion for another person, even if their beliefs and desires are different. In preparation for writing this book, I read transcripts and descriptions of thousands of horrific events, listened to personal stories of survivors from financial ruin and war, worked with abused children who were crucified by unfit parents, and watched both fictional films and documentaries that portrayed psychopaths, dictators of totalitarian regimes, and their hapless victims. As one often does in these circumstances, I developed a tougher skin over time. But I have never lost track of the human travesties that result from evil. As my father’s story suggests, I have also not lost sight of the fact that we are a species that has done great good, and will continue to do so in the future. Nonetheless, to provide a sound and satisfying explanation of evil we must avoid falling into more romantic interpretations of the human condition. Our best protection is science. This is the position I will defend. The topic of evil is massive. This is, however, a short book, written without exhaustive references, in-depth descriptions of our atrocities, and comprehensive engagement with the many theories on offer to explain evil. What I offer is my own explanation of evil, of how it evolved, how it develops within individuals, and how it affects the lives of millions of innocent victims. It is a minimalist explanation of evil that is anchored in the sciences. I believe, as do many scientists, that deep understanding of exceptionally complicated phenomena requires staking out a piece of theoretical real estate with only a few properties, putting to the side many interesting, but potentially distracting details. This book extracts the core of evil, the part that generates all the variation that our history has catalogued, and that our future holds. Sincerely, Nu eon— Hauser Evilicious. Front matter 4 HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_012750

Page 5 - HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_012751

Acknowledgements I wrote this book while my cat, Humphrey Bogart, sat on my desk, staring at the computer monitor. Though he purred a lot, and was good value when I needed a break, he didn’t provide a single insight. Nor did our other pets: a dog, rabbit, and two other cats. For insights, critical comments on my writing, comfort, and endless love and inspiration, there is only one mammal, deliciously wonderful, and without an evil bone in her body — my wife, Lilan. Mare Aidinoff ... a Harvard undergraduate who joined me early on in this journey, digging up references, collecting data, arguing interpretations, sharing my enthusiasm, while offering his own. Kim Beeman and Fritz Tsao ... my two oldest and closest friends. They have some of the richest minds around. Their knowledge of film, literature and the arts is unsurpassed. Their capacity to bring these riches to the sciences is a gift. Noam Chomsky... for inspiration, fearless attacks on power mongering, and friendship. Errol Morris... for heated discussion, camaraderie, and insights into evil through his cinematographic lens and critical mind. Many colleagues, students, and friends provided invaluable feedback on various parts of the book, or its entirety: Kim Beeman, Kent Berridge, George Cadwalader, Donal Cahill, Noam Chomsky, Jim Churchill, Randy Cohen, Daniel Dennett, Jonathan Figdor, Nick Haslam, Omar Sultan Haque, Lilan Hauser, Bryce Huebner, Ann Jon, Gordon Kraft-Todd, Errol Morris, Philip Pettit, Steven Pinker, Lisa Pytka, Richard Sosis, Fritz Tsao, Jack Van Honk, and Richard Wrangham. My agent, John Brockman...not only a great agent but a wonderful human being who supported me during challenging times. My editors at Viking/Penguin, Wendy Wolff and Kevin Doughten. Tough when needed. Supportive when needed. A unique blend. The book is all the better for it. Hauser Evilicious. Front matter re) HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_012751

Page 6 - HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_012752

Table of Contents Prologue. Evilution Chapter 1. Nature’s secrets Chapter 2. Runaway desire Chapter 3. Ravages of denial Chapter 4. Wicked in waiting Epilogue. Evilightenment Hauser Evilicious. Front matter 6 HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_012752

Sponsored

Page 7 - HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_012753

Prologue: Evilution “There is no such thing as eradicating evil [because] the deepest essence of human nature consists of instinctual impulses which are of an elementary nature... and which aim at the satisfaction of certain primal needs.” -- Sigmund Freud I was drowning. This was not the first time. It was also not because I was a poor swimmer. I was 14 years old. A boy named Lionel James, who was the same age but twice my size, was shoving my head under water, roaring with laughter as I struggled to gasp some air. I usually managed to avoid Lionel in the pool, but sometimes he got the best of me while I was playing with friends. Lionel wasn’t the only one who bullied me in junior high school. He was part of an evil three pack, including Ronnie Paxton and Chris Joffe, each much larger and stronger than I. Almost daily they locked me inside of the school’s lockers, bruised my arms by giving me knuckle-punches, and gave me purple-nurples by twisting my nipples. This was no fun for me. For James, Paxton, and Joffe it was delicious enjoyment. Sometimes, while I was locked in my locker, my math teacher would let me out and then ask “Why do you get yourself into these situations?” Though I had great respect for my teacher’s math abilities, and actually had a crush on her, she was socially daft. Did she think I asked to be packaged up in the locker by my tormenters? It was sheer humiliation. One day my mother noticed the bruises. Horrified, she asked what happened. I reluctantly told her the story. She said we were going to talk with the principal. I told her I would prefer water drip torture. She understood and we never went to see the principal. The person who rescued me from my misery was my father, a man who had lived through the war as a child, running from village to village to escape the Nazis, and in so doing, confronted thuggish farm boys whose weight far exceeded their IQ. My father, upon hearing that I didn’t want to go to school anymore, offered a compromise: he would pick me up for lunch every day if I kept going to classes. I agreed, relishing the idea of escaping the lunch-time scene at school where James, Paxton and Joffe pummeled me at will without getting caught. Hauser Prologue. Evilution 7 HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_012753

Page 8 - HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_012754

A month passed. I felt better. My father told me that it was time to go back to lunch at school, but with a plan, one centered around the notion of respect. The only way to command it from my tormenters was to fight back. “But Dad,” I said, “if I hit them, they will crush me.” “They might,” he said, “but you will have gained some respect, and they may turn their attention to someone else.” It seemed like a remarkably stupid idea. But my father lived through a war and fought his way to respect among the thugs in every village school. I decided to give it a go. I went back to school. Soon thereafter, I found myself standing behind Paxton who displayed biceps bigger than my head. I figured I had only one shot. I tapped him on the shoulder and swung as hard as I could, hitting him square in the chest. What aim. What perfection. What wasted energy. With no more than a flinch, Paxton looked down at me, fury in his face, and grunted “What’s up with you?” With tears running and lips trembling, I sputtered “I can’t take it anymore. You, Joffe, and James are constantly lad hitting me and locking me in the lockers. I can’t take it!” And then, as if his entire brain had been rewired, serotonin surging to provide self-control, dopamine flowing to shift his sense of reward, the hulk spoke: “Really? Okay, we’ll stop.” And just like that, Paxton, Joffe and James stopped. No more locker games, no more bruises. They even saw me as a useful resource, someone who could help them pass some of their exams. From victim to victory. I was fortunate. Many are not. Thousands of children throughout the world are persecuted in a similar way but never fight back or if they do, are crushed for trying. Some are pushed so hard that they commit suicide, tragedies that increasingly make headline news reports. The fact that bullies often torment their victims for personal gain, cause great harm, and often enjoy the experience — as did Lionel James — fits well with a common view of evil. On this view, we think of someone as evil if they inflict harm on innocent others, knowing that they are violating moral or legal norms, and relishing the abuse delivered. But what of bullies who, due to immaturity or brain deficits, simply don’t understand the scope of moral boundaries? What if they impose great harm on their victims, but don’t enjoy the experience? What if the victims are not entirely innocent, such as those who double-time as bullies? We can debate questions like these on philosophical grounds, attempting to refine what, precisely, counts as an act of evildoing as opposed to some mere moral wrong, like breaking a promise or having an affair while married. Many have. I don’t believe, however, that this is how we will achieve our deepest understanding. Instead, I turn to the sciences of human nature, focusing on cases where people directly or indirectly cause excessive harm to innocent others as the essence of evil. To explain this form of evil, we must dissect the underlying psychology, the brain circuits that generate this psychology, the genes that build brains, and the evolutionary history that has sculpted the genetic ensemble that makes us distinctively human. This is the approach I pursue. If ’m nght about this approach, not only will we gain Hauser Prologue. Evilution 8 HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_012754

Page 9 - HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_012755

a deeper understanding of how and why our species has engaged in evildoing, but we will learn about our own individual vulnerability to follow suit. This prologue provides a sampling of the central ideas minus the rich evidence and explanations that follow in the four core chapters of this book. A brief history of malice Homo sapiens, the knowing and wise animal, has logged an uncontested record of atrocities, despite moral norms prohibiting such actions: no other species has abducted innocent children into rogue armies and then killed those who refused to kill, tossed infants into the air as targets for shooting practice, gang raped women to force them to carry the enemy’s fetus to term while destroying the souls of their powerless husbands, and mutilated and burned men to death because more humane forms of killing were less effective and enjoyable. These are horrific acts. They abound globally and across the ages. Many scholars have judged them as evil. Despite the pervasiveness of these atrocities, evil is commonly perceived as a defect, an unfortunate malignancy that has engulfed and metastasized within our species’ essential goodness. Evil is also denied, relegated to mythology, the delusional imagination of a few madmen, the propaganda of imperialist nations, or the result of a rare mutation. Perhaps because of these impressions, we have an obsessive fascination with evil, evidenced by our fertile capacity to create and then consume films about genocide, cunning rapists, master criminals, corporate raiders, psychopaths and serial killers. We are of two minds, wanting to hide from the atrocities of evil while feeding our insatiable appetite for more. To understand evil is neither to justify nor excuse it, reflexively converting inhumane acts into mere accidents of our biology or the unfortunate consequences of bad environments. To understand evil is to open a door into its essence, to clarify its causes. In some cases, understanding may force us to exonerate the perpetrators, recognizing that they harbored significant brain damage and as a result, lacked self-control or awareness of others’ pain. In other cases, understanding will reveal that they knowingly caused harm to innocent others, relishing the devastation left behind. By describing and understanding an individual’s character with the tools of science, we are more likely to make appropriate assignments of responsibility, blame, punishment, and future risk to society. To understand evil requires facing our species’ sustained record of atrocities, laying out a variety of cases for inspection. Former Reverend Lawrence Murphy was responsible for over two hundred instances of sexual abuse, luring innocent deaf children in with a saintly smile. Charles Manson, the illegitimate son of a sixteen year old woman and the self-proclaimed father of dozens of runaway women, was responsible for the brutal death of five people by means of 114 knife jabs, while also prostituting his Hauser Prologue. Evilution 9 HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_012755

Sponsored

Page 10 - HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_012756

lovers, beating his wife, selling drugs, and stealing cars. Former Chairman of the NASDAQ stock exchange, Bernard Madoff, was responsible for initiating a Ponzi scheme involving money laundering, perjury, and mail fraud that caused thousands of people to suffer financial ruin. Jane Toppan, born Honora Kelley, was an American nurse who was responsible for killing over 30 patients by drug overdose, stating in her testimony that she experienced a sexual thrill when she held dying patients, and that her goal in life was to kill more innocent people than anyone else in history. Former military specialist Charles Granger was responsible for forcing nudity and sex among the Iraqi prisoners of Abu Ghraib, putting individuals on dog leashes, depriving them of their senses with head bags, and piling naked bodies into photographed still lifes, orchestrations that led to the ultimate humiliation and dehumanization of these prisoners. Depending upon how we think about the problem of evil, we might consider the individuals noted above as minor evildoers or not evil at all because the harms were rather insignificant, because their goal wasn’t to directly harm anyone and then enjoy the trail of damage, or because they lacked the mental capacity to assume responsibility for the atrocities committed. These individuals pale in comparison with the most unambiguously radical evildoers of the 20-21* century — the dictators Idi Amin, Francisco Franco, Adolf Hitler, Kim Jong-il, Slobodan Milosevic, Pol Pot, Josef Stalin, Charles Taylor, and Mao Zedong. These men were responsible for the brutal deaths of approximately 80 million people combined. Most were mentally healthy, at least in terms of clinical diagnoses. Many relished their atrocities. All devised over-the-top means of ending lives. Whether by enticing or coercing their followers to torture, gang rape, and butcher human flesh, they went beyond what was necessary to get rid of unwanted others. These are excessive harms, carried out with excessive techniques. In this book, I will not only explore these extreme cases, but more mundane ones as well. Each case helps shape our understanding of what propells some individuals to cause harm on small or large scales, while others avoid it entirely, despite temptations to the contrary. Why and How? To explain the landscape of human atrocities, from Reverend Lawrence Murphy to Mao Zedong, we need an account of why we evolved this capacity and how it works. I will explain both of these problems using the theories and evidence of science. Why? Evil evolved as an incidental consequence of our unique form of intelligence. All animals show highly specialized abilities to solve problems linked to survival. Honey bees perform dances to tell others about the precise location of nutritious pollen, providing an information highway that lowers the Hauser Prologue. Evilution 10 HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_012756

Page 11 - HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_012757

costs of individual foraging challenges. Meerkats teach their young how to hunt dangerous but energy- rich scorpion prey, providing an education that bypasses the risks of trial and error learning. Humans unconsciously wrinkle their noses and pull back their lips into an expression of disgust that communicates information about disease-ridden and toxic substances, thereby lowering the costs of sickness to others who might be exposed. Each of these specializations involve exquisitely designed neural circuits and sensory machinery. Each specialization is used for one and only one problem — except in humans. Animal thoughts and emotions are like monogamous relationships, myopically and faithfully focused on a single problem for life. Human thoughts and emotions are like promiscuous relationships, broad-minded and liberated, free to couple as new problems surface. Unlike any other animal, the thoughts and emotions we use to solve problems in one domain can readily be combined and recombined with thoughts and emotions from other domains. This is powerful, providing great flexibility in addressing novel problems, some of which we create for ourselves. Disgust provides an example. Disgust originally evolved as an adaptive response to detecting substances that are toxic to our health, especially substances that are outside of the body but should be inside: feces, urine, blood, and vomit. Within the circulation of a promiscuous brain, however, disgust journeys to distant problems, including the moral attitude of vegetarians toward meat eaters, our revulsion toward incest, and abhorrence of gratuitous torture. This journey involves the same brain mechanism that serves original disgust, together with new connections that give voice to our moral sense. Promiscuity enables creativity. What the sciences reveal is that the capacity for promiscuous thinking was realized by evolutionary changes in the number of newly wired up brain areas. By increasing these connections, it was possible, for the first time, to step outside the more narrow and specialized functions of each particular brain area to solve a broader range of problems. Though we don’t know precisely when these changes occurred, we know they occurred after our split from the other great apes — the orangutans, gorillas, bonobos and chimpanzees. We know this from looking at both the brains of these species, as well as the ways in which they use tools, communicate, cooperate, and attack each other. Not only are there fewer connections between different regions of the brain, but their thinking in various domains is highly monogamous, faithfully dedicated to specific adaptive problems. Empowered by our new, massively connected and promiscuous brain, we alone migrated into and inhabited virtually every known environment on earth and some beyond, inventing abstract mathematical concepts, conceiving grammatically structured languages, and creating glorious civilizations rich in rituals, laws, and beliefs in the supernatural. Our promiscuous brain also provided us with the engine for evil, but only as an incidental consequence of other adaptive capacities, including those that evolved to harm others for the purpose of surviving and reproducing. Hauser Prologue. Evilution il HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_012757

Page 12 - HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_012758

All social animals fight to gain resources, using highly ritualized behaviors to assess their opponents and minimize the personal costs of injury. Changes in hormone levels and brain activity motivate and reward the winners, and minimize the costs to the losers. In a small corner of the landscape of aggressive fighting styles are an elite group of killers, animals that go beyond harming their opponents to obliterating them: ants, wolves, lions, and chimpanzees. When these species attack to kill, they typically target adult members of neighboring groups, using collaborative alliances to take out lone or otherwise vulnerable victims. The rarity and limited scope of this form of lethal aggression is indicative of monogamous thinking, and tells us something important about the economics — especially the costs and potential rewards of eliminating the enemy, as opposed to merely injuring them. Killing another adult is costly because it involves intense, prolonged combat with another individual who 1s fighting back. The risks of significant personal injury are therefore high, even if the potential benefit is death to an opponent. As the British anthropologist Richard Wrangham has suggested, animals can surmount these costs by attacking and killing only when there is a significant imbalance of power. This imbalance minimizes the costs to the killers and maximizes the odds of a successful kill. Still, the rarity of killing reinforces an uncontested conclusion among biologists: all animals would rather fight and injure their opponents than fight and obliterate them, assuming that obliteration is costly to the attacker. In some cases, we are just like these other animals — killophobic. Historical records, vividly summarized by Lieutenant Colonel Dave Grossman in his book On Killing, reveal that in some situations, soldiers avoid killing the enemy even though they could have. For example, despite the fact that Civil War regiments had the potential to kill 500-1000 individuals per minute, the actual rate was only 1-2 per minute. This suggests that under some conditions, killing another when you can see the whites of their eyes is hard. But as the history of genocides reveal, we have evolved ways to bypass this limitation, making us killophilic in a variety of situations. Our brain’s unique capacity for denial is one of the liberating factors. By recruiting denial into our psychology’s artillery, we invented new ways of perceiving the enemy or creating one, distorting reality in the service of feeding a desire for personal gain. Denial, like so many aspects of our psychology, generates beneficial and toxic consequences. Self-deceiving ourselves into believing that we are better than we are is a positive illusion that often has beneficial consequences for our mental and physical health, and for our capacity to win in competition. Denying others their moral worth by reclassifying them as threats to our survival or as non-human objects is toxic thinking. When we deny others their moral worth, the thought of killing them is no longer aversive or inappropriate. If we end someone’s life in defense of our own, we are following our evolved capacity for survival. When we destroy a parasite, we are also protecting our self-interests to survive. And when we destroy an inanimate object or lock it away, there is no emotional baggage because we have bypassed the Hauser Prologue. Evilution 12 HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_012758

Sponsored

Page 13 - HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_012759

connection to individual nghts; we have cut out morality as the governor. This suite of transformations, enabled by our promiscuous brain, allowed us to occupy a unique position within the animal kingdom as large scale killers. Chimpanzees only kill adults when there are many attackers against one victim, with the vast majority of kills focused on individuals outside of their own group; most kills within the group are aimed at infants, where the costs to the attacker are low. Though humans also kill members of enemy groups when there are many against one —a pattern that is common among hunter-gatherers and other small- scale societies — we depart from this narrow pattern in terms of numbers and the array of potential victims. When humans kill, we go at it with many against many, one against one, and even one against many, including as victims both those outside of our group and those within, young and old, same and opposite sex, and mating partner and competitor. Add the chimpanzee’s adaptive capacity for coalitionary killing to the promiscuous capacity of the human brain, and we arrive at a uniquely aggressive species, one capable of inflicting great harm on others in any context. Though the modern invention of scud missiles and stealth bombers undoubtedly enriched our capacity to kill on a large scale by putting distance between killers and victims, these weapons of mass destruction were not necessary. Today, we need only travel back a few years to 1994 to witness the machete genocides of Rwanda, a painful memory of our capacity to wipe out close to a million people in 100 days with hand to hand combat. This is excessive harm, enabled by our ability to use denial to minimize the perceived costs of killing another person and to motivate the anticipated benefits. Denial turns down the heat of killing another and turns us into callous predators. Evolutionary changes in the connections to the brain’s reward system provided a second, cost- offsetting step, allowing us to move into novel arenas for harming others. When an animal wins a fight, the reward circuitry engages, providing a physiological pat on the back and encouragement for the next round. This same circuitry even engages in anticipation of a battle or when watching winners. The reward system is important as it motivates competitive action in situations that are costly. There is one situation, however, where the reward system is remarkably quiet, at least in all social animals except our own: detecting and punishing those who attempt to cheat and free-ride on others’ good will. Punishment carries clear costs, either paid up front in terms of resources expended on physically or psychologically attacking another, or paid at the end if the victim fights back or retaliates. These costs can be offset if punishers and their group benefit by removing cheaters or teaching them a lesson. Among animals, punishment is infrequently seen in vertebrates, especially our closest relatives the nonhuman primates. When it is seen, the most common context is competition, not cooperation. Like lethal killing, then, punishment in animals tends to be restricted to a narrow context. Like lethal killing, punishment in animals is psychologically monogamous. Hauser Prologue. Evilution 13 HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_012759

Page 14 - HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_012760

Punishment in humans is emblematically promiscuous. We castigate others whenever they violate a social norm, in both competitive and cooperative situations, targeting kin and non-kin. Punishment is doled out by the individual directly harmed and also by third party onlookers. We use both physical and non-physical means to discipline cheaters, including ostracism. Punishment’s landscape is vast. The idea I develop here, building on the work of scholars in economics, psychology, and anthropology, is that our species alone circumvented the costs of punishment as an incidental consequence of promiscuity, including an intimate coupling between the systems of aggression and reward. As several brain imaging studies reveal, when we either anticipate or actually punish another, or even witness punishment as a mere bystander, our reward circuitry delivers a honey hit. Delivering just deserts, or watching them delivered, is like eating dessert. We absorb the costs of punishment by feeling good about ratting out the scourges, banishing them from society, and sometimes from life itself. Ironically, as the economist Samuel Bowles has suggested based on mathematical models and a synthesis of the historical record, punishment can strengthen solidarity and cooperation within the group, while simultaneously enhancing antagonism and prejudice toward those outside the inner sanctum. Ironically, the psychology that benefited cooperation among like-minded others may also have functioned to destroy those who have different beliefs and values. The emergence of promiscuous punishment was a momentous event in human history, a celebration of exquisite brain evolution and adaptive design. But this achievement carried a hidden cost, a debt that we continue to pay: A mind capable of feeling good about punishing in the name of virtue is a mind capable of doing bad to feel good. It is a mind that finds real or simulated violence entertaining and seeks ways to satisfy this interest. It is a mind that enjoys watching others suffer while singing O Schadenfreude. It is a mind that is capable of feeling good about killing others who are perceived as parasitic on society. It is a mind that can override the anticipated costs of killing by fueling a taste for killing. Desire, denial, aggression and reward are each associated with specific psychological processes, distinct evolutionary histories, and specific adaptive problems. When processed by a promiscuous brain, these systems connect in ways that are both beneficial to human welfare and deeply deleterious. How? Evil occurs when individuals and societies allow desire for personal gain to combine with the denial of others’ moral worth to justify the use of excessive harms. Everyone has desires, resources they want and experiences they seek. Our desires motivate us into action, often to fulfill personal needs or to help others. We all desire good health, fulfilling relationships, and knowledge to explain the world. Some also desire great wealth and power, each culture weighing in on its signature vision of what counts: money, land, livestock, wives, and subordinates. The desire system motivates action in the service of Hauser Prologue. Evilution 14 HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_012760

Page 15 - HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_012761

rewarding experiences. Some actions have benign or even beneficial consequences for the welfare of others, while others have malignant and costly consequences. Exquisite studies pioneered by the American cognitive neuroscientist Kent Berridge have uncovered the core elements of pleasure, including distinctive systems of wanting, liking and learning. We, and hundreds of other species, often want things we like, and like things we want. This is, obviously, an adaptive coupling. Thanks to experiments at the level of genes, neurons, and behavior, we can tease apart these three systems. Thanks to naturally occurring situations, we can watch these systems come unglued over the course of addictions, leading to the paradoxical and maladaptive situation of wanting more and more, but liking the experience less and less. Addictions, as archetypal examples of excess, provide a model for thinking about evil and its trademark signature of excessive harm. The paradoxical decoupling between wanting and liking is seen most clearly in studies of obesity in rats and humans, where individuals develop skyrocketing desires for food, but fail to experience comparable pleasure from eating. By definition, those who become obese are prone to eat in excess. One reason they do is because eating, or even seeing images of food, no longer delivers the same honey hit to the brain as in their pre-obesity days. The reward system turns off when we turn to excess. This is adaptive because nothing in excess is good. But because the wanting system runs independently, the adaptive response by the liking system has the unfortunate consequence of making us want more even though we enjoy it less. The proposal I develop in this book is that the same process is involved in evil, especially its expression of excessive harm. It is a process that is aided by denial. Everyone engages in denial, negating certain aspects of reality in order to manage painful experiences or put forward a more powerful image. But like desire, denial has both beneficial and costly consequences for self and others. When we listen to the news and hear of human rights violations across the globe, we often hide our heads in the sand, plug our ears, and carry on with our lives as if all is okay on planet Earth. When doctors have to engage in slicing into human flesh to perform surgery, they turn off their compassion for humanity, treating the body as a mechanical device, at least until the surgery is over, and the patient awakes, speaks and smiles. When we confront a challenging opponent in an athletic competition or military confrontation, we often pump ourselves up, tricking our psychology into believing that we are better than we are. Denial turns down the heat of emotion, allowing a cooler approach to decision making and action. But doctors in denial concerning the moral worth of others can be convinced to carry out heinous operations for the “good” of science or the purity of their group, and military leaders in denial of an opponent’s strength can lead their soldiers to annihilation. Individuals in denial can reject different aspects of reality in the service of reward, whether it is personal gain, avoiding pain, or enabling the infliction of pain on others. Hauser Prologue. Evilution 15 HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_012761

Sponsored

Page 16 - HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_012762

In a competitive world with limited resources, our desire system never rests. This is a good thing as it motivates us to take care of our self-interests and strive for bigger and better. But a desire system that never sleeps is a system that 1s motivated to accrue ever larger coffers or power. To satisfy this inflationary need is often not possible without harming others, either directly or indirectly. To offset the costs of harming another, desire recruits denial. This is a recipe for evil and the creation of excessive harms. It is a recipe that takes two, often benign and highly adaptive ingredients that are essential for motivating action and promoting survival, and combines them into an explosive outcome. Seen in this way, our capacity for evil is as great as our capacity for love and compassion. Evil is part of human nature, a capacity that can’t be denied. What I will show is both how this capacity works, and how some of us, due to biological inheritance and environmental influence, are more likely to end up as evildoers. Historical material on the lives of Franz Stangl and Adolf Eichmann, leaders in the Nazi annihilation of Jews, illustrates how desire and denial combine within individual minds to create excessive harms. Although this is a historical example, focused on the lives of only two men, stories like theirs have been recounted hundreds of times, all over the globe and across time. This pattern points to common mechanisms, identified in detail by the sciences of human nature. Stangl was a politically motivated man with a burning desire to climb to the top of the Nazi hierarchy. A clear path opened when he was appointed commander of the Polish prison Treblinka. Unbeknownst to Stangl, Treblinka was one of the Nazi’s concentration death camps. To fulfill his desire for power therefore required harming thousands of others, or more accurately, commanding Nazi soldiers to harm others on his behalf. But since Stangl had no burning desire to harm the Jews, he dehumanized them, transforming living, breathing, feeling, and thinking people into lifeless “cargo” — his own expression. Stang] was dry-eyed as officers under his command killed close to one million Jews, one third of them children. The reward? Power and status within the Nazi hierarchy. The death of innocent Jews was a foreseen consequence of Stangl’s desire for power, not his direct goal. Eichmann, Lieutenant Colonel in the Nazi regime, was considered one of the central architects of the Final Solution, the master plan for the extermination of Jews. Eichmann denied Jews their humanity by championing the pamphlets and posters that portrayed them as vermin and parasites. This dehumanizing transformation empowered Eichmann’s belief that cleansing was the only solution to German integrity and power. Eichmann’s reward? Elimination of the Jews. Unlike Stangl, killing Jews was rewarding. As the historian Yaacov Lozowick stated “Eichmann and his ilk did not come to murder Jews by accident or in a fit of absent-mindedness, nor by blindly obeying orders or by being small cogs in a big machine. They worked hard, thought hard, took the lead over many years. They were the alpinists of evil.” Hauser Prologue. Evilution 16 HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_012762

Page 17 - HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_012763

Stang] and Eichmann: two different routes into evil. Both possible and both equally lethal to humanity. This is a lean explanation of why evil evolved and how it develops within individuals and societies. It is an explanation that strips evil down to its root causes, focusing on the core psychological ingredients that enable us to violate moral norms and cause excessive harms to innocent others. A difficult journey This book takes you on a journey into evil. It is a story about our evolutionary past, our present state of affairs, and the prospects for our future. It is as much a story about you and me, as it is about all of our ancestors and future children. It is a story about the nature of moral decay and the prospects of moral growth. It is story about society’s capacity to engineer great harm, and about our own individual responsibility to avoid joining in. Explaining how our genes create brains that create a psychology of desire and denial that leads to excessive harms provides a satisfying explanation for the landscape of evil. It explains all varieties of evil by showing how particular genetic combinations can create moral monsters and how particular environmental conditions can convert good citizens into uncaring killers and extortionists. This explanation will not allow us to banish evil from the world. Rather, it will enable us to understand why some individuals acquire an addiction to feeling good by making others feel bad, and why others cause unimaginable harm to innocent victims while flying the flag of virtue. This, in turn, will help us gain greater awareness of our own vulnerabilities by monitoring the power of attraction between desire and denial. Hauser Prologue. Evilution 17 HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_012763

Page 18 - HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_012764

Endnotes: Prologue. Evilution Recommended books: There are numerous books about evil, most written by philosophers, theologians, historians, political scientists, and legal scholars. The following recommendations are for books about evil written by scientists. They are terrific, I have learned a great deal from them, and some of their ideas powerfully enrich the pages between these covers. Baumeister, R. F. (1999). Evil. Inside human violence and cruelty. New York, W.H. Freeman. Baron-Cohen, S. (2011). The Science of Evil. New York, Basic Books. Oakley, B. (2007). Mean Genes. New York, Prometheus Books. Staub, E. (2010). Overcoming Evil. New York, Oxford University Press. Stone, M. H. (2009). The Anatomy of Evil. New York, Prometheus Books. Zimbardo, P. (2007). The Lucifer Effect. New York, Random House. Notes: * For a philosophical account of the nature of goodness that treats evil as a deviation from our species’ repertoire, see Philippa Foot Natural Goodness (2001, Oxford, Clarendon Press). * For an explicit, philosophical argument for the connection between pleasure and evil, see Colin McGinn‘s Ethics, Evil and Fiction (1997, Oxford, Oxford University Press). For a comprehensive discussion of evil by a philosopher, including important critiques of the existing literature, see John Kekes’ The Roots of Evil (2007, Ithaca, Cornell University Press) * On lalling throughout history: Wrangham, R.W. & Glowacki, L. (in press). Intergroup aggression in chimpanzees and war in nomadic hunter-gatherers: evaluating the chimpanzee model. Human Nature; Bowles, S. (2009). Did warfare among ancestral hunter-gatherers affect the evolution of human social behaviors? Science, 324, 1293-1298; Choi, J.-K., & Bowles, S. (2007). The coevolution of parochial altruism and war. Science, 318, 636-640; Grossman, D. (1995). On killing: the psychological costs of learning to kill in war and society. New York, NY: Little, Brown. * For a summary of research on desire, especially the elements of wanting, liking and learning, see Berridge, K.C. (2009). Wanting and Liking: Observations from the Neuroscience and Psychology Laboratory. Inquiry, 52(4), 378-398; Kringelbach, M.L., & Berridge, K.C. (2009). Towards a functional neuroanatomy of pleasure and happiness. Trends Cognitive Science 13(1), 479-487. * The most serious treatment of Stangl can be found in the penetrating interview by Gitta Sereny (1974, Into that Darkness: From Mercy Killing to Mass Murder. London: Random House). There have been different treatments of Adolf Eichmann, most famously by Hannah Arendt in her Hichmann in Jerusalem: A report on the banality of evil. (1963, New York, Viking Press). Arendt’s perspective on Eichmann as an ordinary gentleman who simply followed orders has been seriously challenged, suggesting that he was anything but a banal evildoer; the quote by Holocaust scholar Yaacov Lozowick is one illustration of the more generally accepted view that Eichmann was a radical evildoer with heinous intentions to Hauser Prologue. Evilution 18 HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_012764

Sponsored

Page 19 - HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_012765

exterminate the Jews. He may have lived a calm and peaceful existence outside of his day job at Nazi headquarters, but this was no ordinary citizen. Quotes: * Quote by Lozowick on Eichmann and banality of evil: Lozowick, Y. (2002) Hitler’s Bureaucrats: The Nazi Security Police and the Banality of Evil. New York, Continuum Press, p. 279. Hauser Prologue. Evilution 19 HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_012765

Page 20 - HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_012766

Chapter I: Nature’s secrets Nature hides her secrets because of her essential loftiness, but not by means of ruse. — Albert Einstein In Charles Darwin’s day, biologists unearthed the mysteries of evolution by means of observation, sometimes accompanied by a simple experiment. This was largely a process of documenting the patterns of variation and uniformity that nature left behind. Only breeders were directly involved in manipulating these patterns, using artificial selection to alter the size, shape, coloration, and lifespan of plants and animals. The Darwins of today continue this tradition, but with new tools, informed by understanding of the genetic code and aided by technical developments in engineering, physics, chemistry, and computer science. These tools allow for deeper penetration into the sources of change, and the causes of evolutionary similarities and differences. They also enable biologists to change the course of evolution and the patterns of development by turning genes off or turning novel ones on, and even creating synthetic organisms in test tubes — a wonderful playground for understanding both questions of origin, change, and extinction. The Darwins of today are cowboys, trailblazing a new frontier of understanding. But like the frontier of the early American wild west, nature holds many secrets and surprises. Sometimes when we break through nature’s guard, we gain fundamental truths about the living world, knowledge that can be harnessed to improve animal and human welfare. But sometimes when we break through, we create toxic consequences and ethical dilemmas. Tampering with nature is risky business as there are many hidden and unforeseen consequences. In 1999, the molecular biologist Joe Tsien and his team at Princeton University tampered with mother nature. Their discovery, published in a distinguished scientific journal, soon filled the newspapers, radio airwaves, and even a spot on Dave Letterman’s late night television show. Tsien manipulated a gene that was known to influence memory, causing it to work over time. This created a Hauser Chapter 1. Nature’s secrets 20 HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_012766

Page 21 - HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_012767

new line of mice with a special accessory: an upgraded memory and learning system. When these new and improved mice ran through an IQ test, they outperformed normal mice. Tsien pulled off an extraordinary engineering trick, creating a lineage of smarter mice. This is cowboy science, showing the power of genetic tampering to open the door to evolutionary changes. In a world of competition, one would imagine that selection should favor these smart mice who have better recall of essential foraging routes, previous social interactions, and places to rest out of harm’s way from predators. But in biology, there are always trade-offs. Benefits in one area of life are often accompanied by costs in others. Several months after Tsien’s report, a follow-up study of the same memory-enhanced mice appeared in print, also in a distinguished scientific journal. But this time there was no media fanfare. The new work was carried out by Min Zhuo at Washington University, an ex-member of Tsien’s lab and a co- author of the original paper. Zhuo’s new paper confirmed that memory-enhanced mice were indeed smarter, but also showed that they were more sensitive to pain, licking their wounds more and for longer periods of time than normal mice. Though it is unclear whether Zhuo’s results reveal heightened pain sensitivity, stronger memories for pain, or some combination of these and other processes, what is clear is that the engineering that led to smarter mice led to much more. Tsien and Zhuo’s work shows that even with targeted, artificial changes in the underlying biology, unanticipated consequences are common. It also shows that deep within the biology of every organism lies hidden capacities and potential for change. Unleashing these sub rosa capacities can have both beneficial and costly consequences for the individual and group. The idea I develop in this chapter is that our capacity for evil evolved as an incidental, but natural consequence of our uniquely engineered brain. Unlike any other species, our brain promiscuously combines and recombines thoughts and emotions to create a virtually limitless range of solutions to an ever-changing environment. This new form of intelligence enabled us to solve many problems, but two are of particular interest given their adaptive consequences: killing competitors and punishing cheaters in a diversity of contexts. But like the painful fall-out from artificially engineering a smarter mouse, so too was there fall-out from the natura/ engineering of a smarter human: a species that experiences pleasure from harming others. This is part of the recipe for evil. This chapter sets out the evidence to support the idea that evil evolved as an incidental consequence of our brain’s design. I begin by discussing the two general processes that landed us in the unforeseen and uninhabited niche of evildoers: the evolution of byproducts and promiscuous connections within the human brain. Because these are general processes, we will take a short reprieve from matters specifically evil. Hauser Chapter 1. Nature’s secrets 21 HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_012767

Sponsored

Page 22 - HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_012768

What’s it for? About 50 million years ago, a family of insects — the Phylliinae — evolved a distinctive piece of anatomy: a body that looks like a leaf. They also evolved the capacity for catalepsy or statuesque stillness. Their leafy body is so exquisitely designed that even predators with superb search images are fooled as they walk or fly by. But from the fact that the leafy body provides these insects with an invisibility cloak, and the fact that this enables them to escape predation, we cannot conclude that the leafy body evolved for predator evasion. What something is used for today may be different from what it evolved for — the difference between current utility and original function. To show that the leafy body evolved for predator evasion, we need to know more, which we do. For one, the leafy body is paired up with a requisite behavioral adaptation: turning to stone. If leaf insects fluttered about as actively as any other insect, their motion alone would cry out to the predators. Optimal effectiveness requires acting like aleaf. But acting like a leaf without the leafy body has its own independent benefits, paying off in terms of predator evasion, as well as sneaking up on potential mates. It would therefore make good sense if stillness evolved first followed by a leafy body. This is precisely what evolution’s record reveals. The adaptive advantage that comes from statuesque stillness and a leafy camouflage can only be measured against the backdrop of today’s predator line-up. If some future-predator evolves more sophisticated abilities to discriminate real leaves from faux leaves, the Phyllinae will be out of luck. This new pressure from predators will, in turn, push for new evasive tricks, thus initiating the classic cycle of predator-prey evolution. What is adaptive for the Phylliinae today, may not be adaptive tomorrow. The comparative study of the Phylliinae raises a class of questions posed by all evolutionary biologists, independently of their taxonomic biases or interests in physiology, morphology, or behavior: How did it originally evolve? What adaptive problem did it solve? Did it evolve to solve one adaptive problem, but over time shift to solve another — a case of what the late evolutionary biologist Stephen J. Gould referred to as an exaptation? Does the exaptation generate profits or losses for survival and reproduction? Is the trait associated with byproducts, incidental consequences of the evolutionary process? What effects, if any, do these byproducts have on survival and reproduction? These questions apply with equal force to evil as they do to language, music, mathematics, and religion. The fact that evil, relative to a leafy body, is more difficult to define, harder to measure, and impossible to experiment upon — at least ethically — doesn’t mean we should take it off the table of scientific inquiry. What it means is that we must be clear about what we can understand, and how we can distinguish between the various interpretations on offer. When we explore the evolution of evil, what are we measuring and what evidence Hauser Chapter 1. Nature’s secrets 22 HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_012768

Page 23 - HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_012769

enables us to distinguish between adaptive and non-adaptive explanations? To answer this question, let us look at two illustrative examples that are more challenging than leafy coverage in insects: the evolution of tameness and religion. Sheep, goats, cows, cats, and dogs are all domesticated animals, created by the forces of artificial selection. All have been transformed from a wild type to an animal that not only lives with us, but sometimes lives for us as food. All are more relaxed, less fearful, and less stressed in the presence of humans than their wild ancestors. Many of these animals seek human companionship. These are the trademark features of tameness. They are also consistently associated with other features that never entered into the breeder’s calculations: floppier ears, curlier tails, more mottled fur, greater sensitivity to human communication, reduced response to predators, earlier sexual maturation, smaller brains, and higher levels of serotonin — a chemical messenger of the brain that regulates self-control. Some of these features appear directly relevant to tameness, whereas others appear entirely irrelevant. For example, serotonin is critically linked to self-control which is critically linked to an animal’s ability to suppress aggression when threatened, which is critically linked to building a life with humans. Mottled fur is not critically linked to any of these benefits. Domestication leads to a pastiche of characteristics, some indicative of the domesticator’s goals and others orthogonal to it. How does the process of domestication, and artificial selection in particular, generate both desired and unanticipated traits? In most cases of animal domestication, we know little about how the wild type changed because the only available information is either anecdotal or based on loose archaeological reconstructions. Consider the domestication of dogs from wolves, and especially the variability among dog breeds. Though it is clear that humans throughout history have bred dogs to serve particular functions, including herding, aggressive defense, and companionship, each of these personality styles is linked to other behavioral and physiological traits. For example, breeds with high activity levels are smaller than breeds with low activity levels, aggressive breeds have higher metabolic rates than docile breeds, and obedient breeds live longer than disobedient breeds. Does selection for aggressiveness cause an increase in metabolic rate or does selection for higher metabolic rate allow for heightened aggressiveness. Because these are all correlations, we don’t know which trait pushed the other to change or whether both traits were favored at the same time. There are two situations that provide a more clear-cut understanding of which feature was favored by selection and which emerged as an incidental byproduct: controlled experiments and domestication efforts that resulted in unambiguously undesirable traits. In the 1950s, the Russian biologist Dmitry Belyaev set out to domesticate the wild silver fox. Over several generations, he selectively bred those individuals who were most likely to allow a human experimenter to approach and hand them food. After Hauser Chapter 1. Nature’s secrets 23 HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_012769

Page 24 - HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_012770

45 years of selective breeding he got what he aimed for: a population of tame foxes, less fearful of humans and more interested in playing with them. But Belyaev also got much more than he aimed for: these tame foxes had floppier ears, curlier tails, smaller brains, higher serotonin levels, and much sharper social skills than their wild relatives. These tame foxes acquired the same package that virtually all other domesticated mammals had acquired: some desired and desirable traits and some surprises. Belyaev’s study shows that even under highly controlled laboratory conditions, artificial selection leaves a trail of unanticipated consequences, traits that come along for the ride. This link between desired and unanticipated features arises because the genes that create these features are like coupled oscillators: changes in the expression of one gene directly link to changes in the expression of others. At the level of the traits — the gene’s expressions — some have no impact on survival or reproduction, while others may increase or decrease these aspects of fitness. We can illustrate this point by looking at an example from dog breeders. Several hundred years ago, dog breeders used artificial selection to create snub-nosed breeds such as the pug, bull dog, and boxer. The idea was to satisfy our aesthetics for diminutive noses, and reduce the size of the dog’s classically large protuberance. Over the course of several generations of picking the smallest-nosed members of the litter, pugs, bull dogs, and boxers emerged. But they also emerged with an unanticipated and maladaptive health problem: all of these breeds have a harder time breathing and staying cool than full-nosed or snouty dogs. No breeder would select for respiratory problems or an inability to stay cool. These traits emerged as costly byproducts of selection for a diminutive nose, and more abstractly, as a byproduct of our aesthetics. As in Tsien’s experiments on memory enhanced mice, when we tamper with nature, we can cause great harm. Research on the evolution of religion provides my second example of how to think about adaptations and byproducts. The different types of religion are like the different dog breeds: distinctive in many ways, but with a large number of shared traits in common. Most religions have a set of rules for group membership and expulsion, ritual practices, and beliefs in the supernatural. These commonalities suggest to some scholars that religion evolved to solve a particular problem, one that all humans confront. That problem is large scale cooperation among unrelated strangers, a topic I pick up in greater detail further on in this chapter. Other species cooperate, usually with a small number of individuals, mostly close kin. As the size of potential cooperators grows, and genetic relatedness among individuals within the group shrinks — adding more unfamiliar strangers to the mix — the potential risks of cooperating with a cheater increases. Religion, and its core features, evolved to diminish this risk and increase the odds of developing a society of stable cooperators. Viewed from this perspective, religion is an adaptation — in the evolved for sense. For those scholars who favor the idea of religion as adaptation, supporting evidence comes from Hauser Chapter 1. Nature’s secrets 24 HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_012770

Sponsored

Page 25 - HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_012771

analyses of historical data together with experiments. Religious groups show higher levels of cooperation, often over longer periods of time, than many other organized, but non-religious groups. Religious groups also tend to last longer as groups than non-religious organizations or institutions. Cooperation among religious groups 1s often facilitated by punishment or the implication of punishment from a deity. In a study of 186 societies by the biologist Dominic Johnson, analyses showed that those who believed in a strong moralizing god, capable of doling out punishment, engaged in higher levels of cooperation, including paying taxes, complying with norms, and repaying loans. These observations are complimented by experiments showing that people are more generous about giving away their money ina bargaining game, and less likely to cheat, when they think about words associated with religion — divine, God, spirit, sacred, prophet — than when they think about neutral words. For example, in the dictator game, involving two anonymous players, one decides how much of a pot of money to give to the other. The recipient has no say, and is thus stuck with whatever the donor offers. In general, donors give either nothing or about half. When primed to think about religion, donors are more likely to give than keep the entire pot, and give more as well. The implication of these results is that the religiously-minded feel that they are being watched. Cueing up words that are indicative of their religious beliefs, heightens their vigilance and their moral obligations. Religion fuels altruism and fends off the temptation to cheat. All of the observations and experiments discussed above are fascinating and relevant to understanding the role of religion in past and present societies. But this evidence is irrelevant for understanding the evolutionary origins of religion. It is irrelevant because it can’t determine whether religion originally evolved to solve the problem of large scale cooperation among strangers or whether it evolved for other reasons but was then used in the context of cooperation. This alternative explanation sees religion as an exaptation. No one doubts that religion provides social cohesion. No one doubts that religion also sends a buzzing reminder to the brain’s moral conscience center. But from a description of what it does today, or even in the distant past, we can’t conclude that it evolved for this purpose. That religious organizations show higher levels of cooperation than non-religious groups doesn’t mean they evolved for cooperation. We also can’t conclude that religion’s effectiveness as social glue relies on uniquely religious psychological thoughts and emotions. Though the creation of and belief in supernatural powers may be unique to religion, other foundational beliefs and emotions are shared across different domains of knowledge: young children attribute intentions, beliefs and desires to unseen causes, including the movement of clouds and leaves; non-religious moral systems use punishment to embarrass, recruit regret, and fuel shame; like many religions, non-religious institutions also attempt to reprogram the thoughts and beliefs of its members — think of all the global rebel operatives that brainwash innocent children into becoming child soldiers. Religion helps itself to non-religious psychology. The utility of Hauser Chapter 1. Nature’s secrets 25 HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_012771

Page 26 - HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_012772

religion looks like a case of exaptation — an expression of human thoughts and emotions that originally evolved to solve problems other than cooperation, but once in place were swiftly adopted for solving problems of cooperation. Further evidence in support of religion as exaptation comes from a follow-up to the dictator game experiment discussed above. If you swap religious words for non-religious but moral words such as civic, duty, jury, court and police, you get the same results: people give more money when thinking about these morally-pregnant, but non-religious words. It is also the case that if you paste up a photograph of eyes next to a money box for coffee, people give more than with a photograph of flowers. What these two studies show is that words and images that make us think about others, especially the possibility that others are watching, turns us into bigger spenders. These psychological transformations are not, however, specific to religion. Some may think that God is watching, but they and others may also think of a white- bearded, gavel-wielding, atheistic judge. We learn three important lessons from the study of tameness and religion, lessons that will propel our discussion of evil. First, distinguish what something evolved for from what it is used for. Second, dissect complicated traits down into their component parts as the parts, together with their inter- dependence, may have different evolutionary histories. Third, the combination of independently evolved capacities can lead to novel adaptations and possibilities. Some combinations lead to altruistic and humane compassion toward those we don’t know. Others lead to virulent hatred and annihilation of those we do know. The brain’s promiscuity is a driving engine for both the good, the bad, and the ugly. From the shackles of monogamy to the freedom of promiscuity Many years ago, some American friends of mine were married in a small village in Tanzania. After the wedding, they went to a local official who was responsible for providing a marriage certificate. On the certificate were three choices, indicative of the type of marriage: Monogamous, Polygynous, and Potentially Polygynous. My friends chuckled, but aimed their pen with confidence at Monogamous. Before they could ink the certificate, however, several Tanzanian men shouted out “NO! At least Potentially Polygynous. Give yourself the option.” Right, the option. The freedom to explore. Among social animals, only a few species pair bond for life, or at least a very long time. This fact is equally true of the social mammals: less than 5% of the 4000 or so species are strictly monogamous. For these rare species, most of their efforts to think, plan, and feel are dedicated to their partner; what’s left over goes into finding food and avoiding becoming dinner. Life is much more complicated for the rest of the social animals. Their social and sexual relationships are more promiscuous, less stable and less Hauser Chapter 1. Nature’s secrets 26 HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_012772

Page 27 - HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_012773

predictable. This unpredictability is partially responsible for changes in the brain. Promiscuous mating systems demand more flexibility, creativity and out of the box thinking. The anthropologist Steve Gaulin explored the idea that a species’ mating system is directly related to its capacity to think. Gaulin started by looking at two closely related species of voles, one monogamous and the other polygynous. In the polygynous vole, males typically mate with multiple females. To achieve this kind of mating success, males have large territories that encompass many smaller female territories. In the monogamous species, the male and female share the same territory, with mating restricted to the couple. These differences in mating system and space usage have two direct consequences: relative to the monogamous male vole, the polygynous male vole must travel much further in a day than the females and must recall where the female territories are located. For a polygynous male vole, mating success depends on long day trips, visiting each of the female territories. For the monogamous male vole, there are no physical or memory challenges as the female is virtually always nearby. Given the costs to a polygynous male vole of forgetting where the females live, there should be strong selection on the memory system. Gaulin confirmed this prediction by showing that polygynous male voles outcompete females of their species in a maze running competition, and also have larger memory systems than females. In the monogamous vole, there are no sex differences in maze running or memory. Gaulin’s work provides a gorgeous example of how evolutionary pressures can act on the brain to create differences in psychological capacity. Other examples abound, including evidence that fruit eaters have larger brains than leaf eaters, primates living in large social groups have larger frontal lobes than those living in smaller groups, and bats living in open habitats have smaller brains than those living in complex closed habitats. In each case, a particular ecological or social pressure — finding ripe fruit, updating the status of numerous social relationships, avoiding obstacles while in flight — sculpts differences in brain anatomy and function. Some of these pressures favor extreme specialization and myopia, whereas others favor a broader vision. Relative to every healthy member of our species, all other animals have tunnel vision. When our ancestors began to migrate out of Africa, the diversity of environments and social opportunities favored generalists with a broad and flexible vision. To appreciate the significance of the human revolution in brain engineering, consider three cases of myopic, but highly adaptive intelligence in other animals, cases that lack the signature of intellectual promiscuity; these cases are of particular interest because they represent the kinds of examples that caused Darwin to doubt the beneficence of God, to reflect upon the cruelty of nature, and to ponder the problem of evil: * The wasp Ampulex compressa tackles a specific species of cockroach, inserts a first stinger into its body to cause leg paralysis and eliminate fighting, then a second Hauser Chapter 1. Nature’s secrets 27 HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_012773

Sponsored

Page 28 - HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_012774

stinger into the brain that causes intense auto-grooming followed by three weeks of lethargy. During this down time, the cockroach turns into a living meal for the wasp’s larvae. *A Brazilian parasitoid wasp of the family Braconidae, lays its eggs inside a particular species of caterpillar, and once the larvae are fully developed, they hatch out of the caterpillar. Though it is strange enough for caterpillars to function like incubators, these innocent larvae were anything but innocent while developing inside the caterpillar. Once the larvae hatch, they are treated to an unprecedented level of care from the caterpillar who, Gandhi-like, foregoes all eating and moving to protect its adopted young, including violent head-swings against any intruder. The wasp has effectively brain- washed the caterpillar, hijacking its evolved instincts to care for its own young. *A solitary wasp in the genus Sce/iphron selectively feeds on the dangerous and much larger black widow spider, using two tricks: it secretes a substance that is like Teflon, allowing it to move into a spider’s web without getting stuck; next, it flails around in the web to attract the spider, and once the spider is positioned above in kill mode, the wasp launches its stinger, piercing the spider right through the brain. End of black widow. If the wasp makes the slightest mistake, end of wasp. The capacity that has evolved in these wasps is myopically focused on one problem, and one problem alone. Despite the mind control and deception that is part of their evolved competence, they don’t deploy these skills in any other context. This highly adaptive and monogamous pattern of thinking runs throughout the animal kingdom and across different contexts, including male cleaner fish that attack female cleaner fish who violate the rules of mucus-eating from their clients, but do not deploy such draconian measures in other situations; birds that feign injury to deter predators from their nest, but deceive in no other context; cheetah mothers who demonstrate to their cubs how to bring down prey, but never provide pedagogical instructions in other relevant domains of development; and monkeys that understand how to use tools generously provided by humans but never create any of their own. Like other animals, we too are equipped with adaptive capacities that evolved to solve particular problems. Unlike other animals, however, these same adaptive specializations are readily deployed to solve novel problems, often by combining capacities. Like wasps, we deceive, manipulate and parasitize others, often cruelly. But unlike wasps, we don’t use these abilities with one type of victim in one context. As long as the opportunity for personal gain is high relative to the potential cost, we are more than willing to deceive, manipulate, and parasitize lovers, competitors and family members. When we attack rule violators, not only do we do so in the context of cheaters who eat but don’t pay, but also deadbeat dads Hauser Chapter 1. Nature’s secrets 28 HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_012774

Page 29 - HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_012775

who fail to care for their young, cads who have extramarital affairs, and trigger-happy murderers who take the lives of innocent people. What changes in the brain enabled us, but no other species, to engage in promiscuous thinking? To understand what changed in the brain, it is useful to paint a few broad-stroke comparisons, and then narrow in on the details. We know, for example, that brain size changed dramatically over the course of our evolutionary history, ultimately reaching three times the size of a chimpanzee’s brain with the appearance of the first modern humans some 100-200,000 years ago. From the archaeological evidence, we can infer that some aspect of the internal workings of the brain — not simply size — must have changed at about the same time in order to explain the appearance of a new material culture of tools with multiple parts and functions, musical instruments, symbolically decorated burial grounds, and cave paintings. Before this period, the material culture of our ancestors was rather uncreative, with simple tools and no symbolism. The new material culture was heralded by a mind unlike any other animal. No other animal spontaneously creates symbols, though chimpanzees and bonobos can be trained to acquire those we invent and attempt to pass on. No other animal creates musical instruments or even uses their own voice for pure pleasure. No other animal buries its dead, no less memorializes them with decorations; ants drag dead members out of their colony area and deposit them in a heap, though this is driven by hygiene as opposed to ceremonial remembrance and respect. Only a species with the capacity to combine and recombine different evolved specializations of the brain could create these archaeological remains. This period in our evolutionary history marks the birth of our promiscuous brain. The brain sciences have helped us see the fine details of this new species of mind. The comparative anatomists Ralph Holloway, James Rilling, and Kristina Aldridge have analyzed brain scans and skull casts of humans and all of the apes: chimpanzees, bonobos, gorillas, orangutans, and gibbons. This sample represents approximately 15 million years of evolution, and includes considerable diversity in mating systems, dietary preferences, use of tools, group size, life span, locomotion style, communication system, aggressiveness, and capacity for cooperation. Thus, gibbons are monogamously pair bonded, live in small family groups in the upper canopies, swinging and singing to defend their territories, never use or create tools, are omnivorous, restrict cooperation to within the family group, and show little aggression. Gorillas are folivores or leaf eaters, live in harem societies, knuckle walk on the ground, rarely use or make tools in the wild, show aggression primarily between harems, communicate with a diversity of sounds, and show limited cooperation even under captive conditions. Chimpanzees are promiscuous, omnivores who hunt for meat on the ground and in the tree tops, create a diversity of tools that are culturally distinctive between regions, communicate with a diversity of sounds, are lethal killers when they confront individuals from a neighboring community, and are cooperative especially in competitive situations. Despite this diversity, nonhuman ape brains are much Hauser Chapter 1. Nature’s secrets 29 HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_012775

Page 30 - HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_012776