HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_017088 - HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_017487

This 400-page government document from the House Oversight Committee appears to be a comprehensive manuscript examining legal and social issues across American history.

This document appears to be a manuscript or a draft of a book, possibly an autobiography or a detailed analysis of legal and social issues, divided into four parts: the author's early life and education, freedom of speech, criminal justice, and the quest for equality and justice. It includes a table of contents outlining various chapters discussing topics ranging from the First Amendment and pornography to capital punishment, race, and the impact of media on the law. The document mentions a wide array of notable figures and legal cases, suggesting a comprehensive exploration of legal and societal changes.

Key Highlights

- •At nearly 192,000 words across 400 pages, this represents one of the lengthier documents in the collection

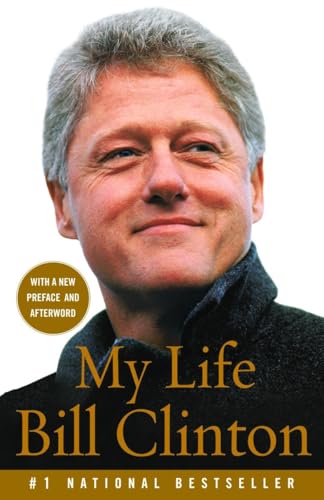

- •References range from presidents like John F. Kennedy and Bill Clinton to legal scholars like Alan Dershowitz and Noam Chomsky, as well as historical figures including Adolf Hitler

- •Covers a broad intellectual terrain including First Amendment rights, criminal justice system reforms, and changing perspectives on race in America

Frequently Asked Questions

Document Information

Bates Range

HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_017088 - HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_017487

Pages

400

Source

House Oversight Committee

Date

April 2, 2012

Original Filename

CURREN DRAFT 04.02.12.docx

File Size

671.55 KB

Document Content

Page 1 - HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_017088

4.2.12 WC: 191694 TOTAL WORD COUNT 191,694 TOTAL PAGES 401 TABLE OF CONTENTS Preface: Ideology as Biography—A life of continuous change We 4391 Pages 9 Part I: From Brooklyn to Cambridge (with stops in New Haven and Washington Chapter 1: Born and religiously educated in Brooklyn We 15,669 Pages 27 Chapter 2: My Secular Education—Brooklyn and Yale We 3811 Pages 6 Chapter 3: My Clerkships: Judge Bazelon and Justice Goldberg We 13969 Pages 24 Chapter 4: Beginning my life as an academic—and its changes over time We 7530 Pages 12 Part Il; The changing sound and look of freedom of speech: from the Pentagon Papers to Wikileaks and from Harry Reems’ Deep Throat to Woodward and Bernstein’s “Deep Throat.” Chapter 5: The Changing First Amendment—New Meanings For Old Words We 5259 Pages 9 Chapter 6 Offensiveness- Pornography: I Am Curious Yellow and Deep Throat We 12,338 Pages 24 Chapter 7 Disclosure of Secrets: From Pentagon Papers to Wikileaks We 6905 Pages 13 Chapter 8: Expressions that incite violence and disrupt speakers We 3545 Pages 6 HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_017088

Page 2 - HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_017089

4.2.12 WC: 191694 Chapter 9: The Right to Falsify History: Holocaust Denial and Academic Freedom Wc 5031 Pages 10 Chapter 10: Speech that Conflicts with Reputational and Privacy Rights We 4685 Pages 9 Part II: Criminal Justice: From Sherlock Holmes to Barry Scheck and CSI Chapter 11: “Death is different’': Challenging Capital Punishment We 3157 Pages 6 Chapter 12: The death penalty for those who don’t kill: Ricky and Raymond Tison We 6392 Pages 20 Chapter 13: Using Science, Law, Logic and Experience to Disprove Murder We 23825 Pages 51 Chapter 14: The changing politics of rape: From “no” means “maybe,” to “maybe” means “no.” We 15644 Pages 29 Chapter 15: The changing impact of the media on the law We 14877 Pages 29 PART IV: THE NEVERENDING QUEST FOR EQUALITY AND JUSTICE Chapter 16: The Changing Face of Race: From Color Blindness to Race-Specific Remedies We 14130 Pages 26 Chapter 17 The crumbling wall between church and state: from separation to christianization We 8883 Pages 16 Chapter 18: From Human Right to Human Wrongs: How the hard left hijacked the Human Rights Agenda Wc 14667 Pages 27 ' Justice John Paul Stevens HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_017089

Page 3 - HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_017090

4.2.12 WC: 191694 Conclusion—Closing Argument: Looking back at my 50 year career and forward to the laws next 50 years. Wc 7047 Pages 13 APPENDIX— VIGNETTES We 8817 Pages 42 (each on separate page) HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_017090

Sponsored

Page 4 - HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_017091

4.2.12 WC: 191694 Alan Dershowitz Takes The Stand: An Autobiography Or Taking the Stand—an Autobiography by Alan Dershowitz Preface: Ideology as Biography—A life of continuous change My legal practice has been described as “the most fascinating on the planet.” Though perhaps hyperbolic, the fact is that during my long career as a lawyer, I have: * represented and counseled presidents, prime ministers, United Nations high officials, judges, senators, actors, musicians, athletes as well as ordinary people who have had the most extraordinary cases; * played a role, sometimes large, sometimes small, in some of the most cataclysmic events of the last half century—from the assassination of JFK, to the forced resignation of Richard Nixon, to the Chappaquiddick investigation of Ted Kennedy, to the impeachment of President Clinton, to the war crimes trials of accused war criminals, to the defense of Israel in international fora. * represented some of the most despised and despicable people on the face of the earth and sat across the table from defendants accused of mass murder, terrorism, war crimes, torture, rape and hate crimes; * — served as a lawyer in some of the most transforming legal cases of the age, including the Pentagon Papers Case, the WikiLeaks investigation, the anti-war prosecutions of Dr. Spock, the Chicago 7, the Weather Underground and Patricia Hearst; * represented some of the most controversial defendants in recent history: OJ Simpson; Claus Von Bulow; Mike Tyson; Leona Helmsley and Michael Milken. This autobiography delves beneath the surface of these cases and causes. It presents an inside account of legal events that have altered history and that continue to have a major impact on the lives of millions of people. What Tocqueville observed two centuries ago—that in our country nearly every great issue finds its way into the courts—is even truer today than it was then. Accordingly, my autobiography will, in some sense, be a history of the last half century as seen through the eyes of a lawyer who > [quote] HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_017091

Page 5 - HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_017092

4.2.12 WC: 191694 was privileged to have participated in many of the most intriguing and important cases and controversies of our era. The law has changed considerably over the past half century. I have not only observed and written about these changes, I have helped to bring some of them about through my litigation, my writing and my teaching. This book presents an account of these changes and of my participation in the cases that precipitated them. It is also an account of one man’s intellectual and ideological development during a dramatic century of world, American, and Jewish history, enriched with anecdotes and behind-the-scenes stories from my life and the lives of those I have encountered. An autobiographer is like a defendant who takes the stand at his own trial. We all have the right to remain silent, both in life and in law. But if one elects to bear witness about his own life, then he or she must tell the truth, the whole truth and nothing but the truth. This commitment to complete candor is subject only to limited privileges such as those between a lawyer and a client, or a husband and a wife. A witness may be questioned not only about his actions, but also about his motivations, his feelings, his biases, and his regrets. In this autobiography, I intend to comply with these rules to the best of my ability. Why then have I waived my privilege of silence and decided to write this autobiography: because I have lived the passion of my times and participated in some of the most transforming, legal and political events of the past half century. In this autobiography, I will describe and explain my role in litigating cases and advocating causes that have changed the political and legal landscape—for better or worse. I will also explain how I litigate difficult cases—the tactics and strategies I have successfully developed over the years. My oath of honesty makes it impossible to hide behind the false modesty that often denies the readers of autobiographies an accurate picture of the impact an author has had on events. Since you’re reading these words, you’ve probably encountered the public Alan Dershowitz—confrontational, unapologetic, brash, tough, argumentative, and uncompromising. Those who know me well—family, friends, and colleagues—hardly recognize the “character” I play on TV [alternative: my TV persona]. They tell me in my personal life, I shy away from confrontation and am something of a pushover. My son Elon says that when people bring me up in conversation, he can instantly tell whether they know me from TV or from personal interactions—whether they know what he calls “The Dersh Character” or “the real Alan.” This sharp dichotomy between my public and private personas was brought home to me quite dramatically, when a major motion picture, Reversal of Fortune, was made about my role in the Claus Von Bulow case, and a character, based on me, was played by Tony Award actor Ron Silver. The New York Times asked me to write an article for the arts and entertainment section on how it feels to watch someone play you on the big screen. The opening scene of the film had my character playing an energetic basketball game with himself—true enough. But when he’s interrupted by a phone call giving him the news that he had lost a case involving two brothers on death row (the Tison brothers, see Chapter 12), he smashes the phone on the pavement. HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_017092

Page 6 - HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_017093

4.2.12 WC: 191694 When I complained to my son, who had co-produced the film, that I don’t throw phones when I lose cases—even capital cases—my son responded: “Dad, you’ve got to get it through your head that the person on the screen isn’t you; it’s your character—‘the Dersh Character.’” He continued to assure me, in his best professional manner, that characters have to “establish themselves” early in the film, and that this “establishing scene” was intended to convey my energy and my passion for the rights of criminal defendants. “If we had several hours, we could have demonstrated your passion by recounting your involvement in many other cases, but we had about a minute; hence the smashed phone.” I wasn’t satisfied. “That scene doesn’t show passion,” I said. “It shows a temper tantrum.” My son tried to explain that a character in a film has to be shown with some faults early on in the film, so that he can “overcome” them. “I know you don’t lose your temper,” Elon assured me smilingly, “but the viewing audience has to see you grow.” Still, I didn’t like being portrayed as a person whose passions—manifested by occasional curses in addition to the smashed phone—are reserved exclusively for his professional life. My “girlfriend” in the film—a mostly fictional character played by Annabella Sciorra—complains loudly that my character has nothing left for the people around him, and my character seems to agree: “My clients are the people I care about.” Poor guy! I hope that’s not me, although I do have to acknowledge that people who know me only professionally assume that I have nothing left for those I love. But the fact is that I reserve a lot of love, loyalty and friendship for family and people close to me. I asked Ron Silver—who knows how important my family and friends are to me—how he felt playing me in way that he knew was something of a stereotype of the passionate lawyer for whom, Oliver Wendell Holmes’ said, “the law is a jealous mistress.” He responded: “I’m playing the public Alan Dershowitz—the one people see on TV and in the newspapers. I can’t get to know the private Alan well enough to play him, and frankly the public isn’t interested in that side of you.” In this book, I will try to interest my readers in both sides of my life, and how each impacts the other, and how both are very much the products of my early upbringing and my lifelong experiences. I think of myself as an integrated whole, though the very different roles I play—as lawyer, teacher, writer, father, husband, friend, colleague—require somewhat different balances among the various elements of my persona. Although this autobiography is my first attempt to explore my life in full, I have written several earlier books that touch on aspects of my public life. The Best Defense dealt with my earliest cases during the first decade of my professional life. Chutzpah covered my Jewish causes and cases. Reversal of Fortune and Reasonable Doubts each dealt with one specific case (Von Bulow and O.J. Simpson). I will try not to repeat what I wrote in those books, though some overlap is inevitable. This more ambitious effort seeks to place my entire professional life into the broader context of how the law has changed over the past half century and how my private life prepared me to play a role in these changes. HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_017093

Sponsored

Page 7 - HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_017094

4.2.12 WC: 191694 I bring to this task a strong and dynamic world view that has been shaped by my life experiences and which has, in turn, shaped my life experiences. In looking back on my life, I am inevitably peering through the prism of the powerful ideology that has provided a compass for my actions. Ideology is biography. Where we stand is the result of where we sat, who we sat next to, what we observed, what happened to us, and how we reacted to our experiences. Ideology is complex. Its causes are multifaceted and rarely subject to quantification. The philosopher, Descartes, who famously said, “I think therefore I am” got it backwards. I am—I was, I will be—therefore I think what I think. The ability to think is inborn—a biological and genetic endowment. The content of one’s thinking—the nature and quality of our ideas—is more nurture than nature. Without human experiences there could be no well-formed ideology, merely simple inborn reflexes based on instinct and genetics.* There is no gene, or combination of genes, that ordains the content of our views regarding politics, law, morality or religion.* Biology gives us the mechanisms with which to organize our experiences into coherent theories of life, but without these experiences—which begin in the womb and may actually alter the physical structures of our brain over time—all we would have are the mechanics of thought and the potential for formulating complex ideas and ideologies. It is our interactions—with other human beings, with nature, with nurture, with luck, with love, with hate, with pleasure, with pain, with our own limitations, with our mortality-—that shape our world views. Among the most enduring and influential human encounters are those experienced at an early age. These include the accidents of birth: to which family, in which place, at which time we happen to come into the world. It is true that most people die with the religion and political affiliation into which they were born (or adopted). Identical twins, separated at birth, may share a common disposition, IQ and susceptibility to disease, but they are likely to share the religious and political affiliations of their adoptive parents. There is little genetic about the factors that directly influence religious, political or other ideological choices. They are largely a function of exposure to external factors.° Many of these external factors are totally beyond the control of the person. They may involve decisions made by others, often before they were even born. Probably the most significant decisions affecting my own life were made by my great grandparents on my father’s side and my grandparents on my mother’s side: the decision to leave the shtetls of Poland and move to New York. Had they remained in Poland, as some of my relatives did, I would probably not have survived the Holocaust, since I was three years old when the systematic genocide began.’ That 3 Quote Steve Pinker “EN on Mark Hauser “Moral Minds.” Drew Weston, George Lakoff. > Kafka once quipped that “the meaning of life is that we die,” and when God told Adam and Eve that if they eat from the tree of knowledge, they will die, he meant they will obtain the knowledge of mortality—which elevated humans above other species. ° This is not to deny the likely influence genetics and biology may have on a predisposition toward homosexuality or other orientations. Nor is it to deny that biological predisposition may influence ideology through the prism of experience. See [cite] [expand] ’ Perhaps, of course, had my forbearers remained in Poland, my father might not have met my mother (although their families lived in neighboring shtetls). Accident, timing and luck determine virtually everything relating to birth. HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_017094

Page 8 - HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_017095

4.2.12 WC: 191694 may be why Jews of my generation are so influenced in their attitudes and ideology by the Holocaust. There but for the grace of God, and the forethought of our grandparents, go we. (In 1999, I wrote a novel Just Revenge, which reflected my dear feelings about the unavenged murders of so many of my relatives.) Once a person is born in a certain place, at a certain time, attitudes and ideology are shaped (in part, because luck always intrudes’) directly by family, religion, culture, neighborhood, childhood friends, teachers and other mentors and role models. Sometimes they are a reaction to these influences. Often they are a combination of both. If ideology is biography, then autobiography must honestly attempt to explore the sources of the author subject’s ideology in his or her life experiences. This requires not only deep introspection, but a willingness to expose—to the reader but also to the writer—aspects of one’s life that are generally kept private or submerged. Everyone has the right, within limits, to maintain a zone of privacy. I have devoted a considerable portion of my professional life seeking to preserve, indeed expand, that zone. But a decision to write an autobiography requires a commitment to candor and openness—a “waiver” (to use a legal term) of much of the right to privacy. I keep fairly complete records of my cases and controversies. My archives are in the Brooklyn College Library where, subject to a few limited exceptions, they are available for all to read. I have published dozens of books, hundreds of articles and thousands of blogs. My professional life has been an open book and the accessibility of my architves—containing letters, drafts and other unpublished material— opens the book even further. But beyond the written record lies a trove of memories, ideas, dreams, conversations, actions, inactions, passions, joys, and feelings not easily subject to characterization or categorization. Fortunately, I have a very good memory (more about that later) and I am prepared to open much of my memory bank in this autobiography, because I believe that the biography that informs my ideology and life choices cannot be limited to the externalities of my career. It must dig deeper into the thought processes that motivate actions, inactions and choices. In the process of self- exploration, I must also be willing to examine feelings and motivations that I have kept submerged, willfully or unconsciously, from my own conscious thought process. I don’t know that I will be able to retrieve them all, but I will try. Nor can I be absolutely certain that all of my memories are photographically precise, since my children chide me that my stories get “better” with each retelling. I believe that my actions, inactions, and choices have been significantly influenced by my upbringing. That might not seem obvious to those who know me and are familiar with my family background. Superficially, I am very different from my parents and grandparents, who lived insular lives in the Jewish shteles of Galicia, Poland, the Lower East side of Manhattan, and the Williamberg, Crown Heights and Boro Park Orthodox Jewish neighborhoods (also “shtetles”) of Brooklyn. My parents and grandparents had little formal education. They rarely traveled beyond their routes to and from work (except for my grandparents’ one-way journeys from Poland to Ellis Island). They almost never attended concerts, the Broadway Theater or dance recitals. They owned no art, few books, and no classical records. They rarely visited museums or 5 An old Yiddish expression says: “Man plans, God laughs.” 8 HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_017095

Page 9 - HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_017096

4.2.12 WC: 191694 galleries. Their exposure to culture was limited to things Jewish—cantorial recitations, Yiddish theater, lectures by Orthodox rabbis, Jewish museums, Catskill Mountain and Miami Beach entertainment. My adult life has been dramatically different. I travel the globe, meet with world leaders, own a nice art collection, am deeply involved in the world of music, theater and other forms of culture, and lead a largely secular life (though I too enjoy cantorial music “borsht belt” humor, and a good pastrami sandwich). Yet I am their son and grandson. Although my life has taken a very different course—both personally and professionally—I could not begin to explain who I am, how I got to be who I am, and where I am heading, without exploring my family background and heritage. It is this history that helped to form me, that caused me to react against parts of it, and—most important—that gave me the tools necessary to choose which aspects of my traditions to accept and which to reject.” I had a very powerful upbringing, having been born to a family with strong views on religion, morality, politics and community service. My neighborhood was tight knit. Everyone had a place and knew their place. Status was important, especially for our parents and grandparents, as was “yichus” (the Yiddish term for ancestry). But I grew up at a time of change, growth, excitement and opportunity. Despite the reality of pervasive anti-Jewish discrimination—in college admission, employment, residency and social clubs—my generation believed there were no limits to what we could accomplish. If Jackie Robinson could play second base for the Brooklyn Dodgers, we could do anything. Maybe that was the reason so many successful people grew up in Brooklyn in the immediate post-war period. (In 1971, I was selected among 40 young scholars from around the country for a distinguished fellowship. When we met in Palo Alto, California, we discovered close to half the group had Brooklyn roots!) We were the breakout generation, standing on the broad shoulders and backbreaking work of our immigrant grandparents and our working class parents. I cannot explain, indeed understand, my own world views, without describing those on whose shoulders I stand, that from which I have broken out, and the experiences that have shaped my life. So I will begin at the beginning, with my earliest memories and the stories I have been told about my upbringing. But formative experiences do not end at childhood or adolescence. They continue throughout a lifetime. Learning never ends, at least for those with open minds and hearts, and, though ideologies may remain relatively fixed over time, they adapt to changing realities and perceptions. Winston Churchill famously quipped, “Show me a young conservative and I’ll show you someone with no heart. Show me an old liberal and I’ll show you someone with no brain.” It is surely true that some people become less idealistic with age, with economic security and family responsibilities. But it is equally true that some young conservatives become more liberal as they ° My dear friend and teaching colleague Steven Pinker believes that parental influence may be overvalued [CITE]. I’m certain that it varies among individuals and families. 9 HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_017096

Sponsored

Page 10 - HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_017097

4.2.12 WC: 191694 seek common ground with their children, while other people remain true to their earlier world views. It depends on the life one has lived. I have been fortunate to live an ever changing life, both personally and professionally, and although my views on particular issues have been modified over time, my basic commitment to liberal values has remained relatively constant, in part because of my strong upbringing and in part because my career has been based on advocating these values. An ancient Chinese curse goes this way: “May you live in interesting times.” One of the worst things a doctor can say after examining you is: “Hmm... that’s interesting.” I have been blessed with living an interesting, if often controversial, life. As an adolescent, I was involved in causes such as justice for the Rosenbergs, abolition of the death penalty, and the end of McCarthyism. As a law clerk, during one of the most dramatic periods of our judicial history, I worked on important civil rights and liberties cases, heard the “I have a dream” speech of Martin Luther King, was close to the Cuban Missile Crisis, and partook of events following the assassination of John F. Kennedy. As a young lawyer, I played a role in the Pentagon Papers case, the forced resignation of Richard Nixon, and the anti-war prosecutions of Dr. Spock, the Chicago Seven, the Weather Underground and Patricia Hearst. I consulted on the Chappaquiddick investigation of Ted Kennedy, on the attempted deportation of John Lennon and the draft case against Mohammad Ali. I was an observer at the trial of accused Nazi war criminal John Demjanjuk and subsequently consulted with the Israeli government about that case. Later in my career, I was a lawyer in the Bill Clinton impeachment, the Bush v. Gore election case, the efforts to free Nelson Mandela, Natan Sharansky and other political prisoners. I participated in the Senate censure of California Senator Alan Cranston, the Frank Snepp CIA censorship case, prosecutions involving the former Yugoslavia in the Hague, the defense of Israel against international war crime prosecution, and the investigation of Wiki-Leaks and Julian Assange. I worked on the appeals of the Jewish Defense League murder case and the Jonathan Pollard spy prosecution. I consulted on the defense of director John Landis, the OJ Simpson double murder case and the Bakke “affirmative action” litigation. I challenged the Bruce Franklin tenure denial at Stanford and appealed the Claus Von Bulow attempted murder conviction, the Leona Helmsley tax case, the Mike Tyson rape prosecution, the conviction of Conrad Black, the Tison Brothers murder case, the “I Am Curious Yellow” censorship prosecution, the Deep Throat case, the nude beach case on Cape Cod and the HAIR censorship case. I participated in the Woody Allen-Mia Farrow litigation, the Michael Milken case, the litigation against the cigarette industry and the wrongful death suit on behalf of Steven J. Gould. I have won more than 100 cases and have been called—perhaps also with a bit of hyperbole—“the winningest appellate criminal defense lawyer in history.” Of the more than three dozen murder and attempted murder cases in which I have participated, I lost fewer than a handful. None of my capital punishment clients has been executed. 10 HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_017097

Page 11 - HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_017098

4.2.12 WC: 191694 Among the people I have advised are President Bill Clinton, Prime Minister Benjamin Netanayu and President Moshe Katsav of Israel, Canadian Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau, Senator Alan Cranston, the Deputy Secretary General of the United Nations, Marlon Brando, Frank Sinatra, Woody Harrelson, Michael Jackson, John Lennon, Natalie Portman, Broadway producer David Merrick, New England Patriot Head Coach Bill Belichick, the actress Isabella Rossellini, the international arms dealer Adnan Khashoggi, singers Carly Simon and David Crosby, basketball player Hakeem Olajuwon, baseball star Kevin Youkilis, football quarterback Tom Brady, saxophonist Stan Goetz, artist Peter Max, cellist Yo Yo Ma, comedian Steven Wright, actor Robert Downey, Jr., several billionaires such as Sheldon Adelson and Mark Rich, authors such as Saul Bellow, David Mamet and Elie Wiesel, and judges, senators, congressmen, governors and other public officials. In addition I have had some of the most interesting cases involving people who are not well known but the cases raised intriguing and fascinating issues. Among these issues are whether a man can be prosecuted for attempted murder for shooting a dead body that he thought was alive, whether a husband can be prosecuted on charges of slavery for not doing anything about his wife’s alleged abuse of domestic employees, whether a husband can be forced to adopt a child and whether a law firm can discriminate in its partnership decision. I have engaged in public debates and controversies with some of the most contentious and influential figures of the age including William F. Buckley, Noam Chomsky, Rabbi Meyer Kahana, Rabbi Adan Steinzaltz, Justice Antonin Scalia, Ken Starr, Elie Wiesel, Vaclav Havel, Golda Meir, Red Auerbach, William Kunstler, Roy Cohn, Norman Mailer, Patrick Buchanan, Norman Podhoretz, Bill O’Reilley, Skip Gates, Alan Keyes, Dennis Prager, Jeremy Ben Ami, Mike Hukabee, Shawn Mann, William Bulger, James Zogby, Jimmy Carter, Richard Goldstone, Norman Finkelstein and many others. I was part of an American team of debaters selected to confront Soviet debaters on a nationally televised debate, during the height of Soviet oppression of Refusenicks, for which William Buckley suggested that the US team be given medals of freedom. I was a regular “advocate” on the nationally-televised Peabody award winning show “The Advocates” on PBS for several years. I have been interviewed by nearly every television and radio talk and news show and have written for most major newspapers, magazines and blogs. This is my 30" book. In recent years, I have devoted considerable energy to the defense of Israel, while remaining critical of some of its policies. The Forward has called me, “America’s most public Jewish defender,” and “Israel’s single most visible defender — the Jewish state’s lead attorney in the court of public opinion.” In 2010, The Prime Minister of Israel asked me to become Israel’s Ambassador to the United Nations—an offer I respectfully declined because I am an American, not an Israeli citizen. I have agreed instead to be available to serve as an American lawyer for Israel before international tribunals. I have also taught thousands of students, many of whom have become world and national leaders. I have learned from each of these experiences, and they too have helped to shape my evolving world views. I have seen the law change, in some respects quite dramatically, in the half century I 11 HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_017098

Page 12 - HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_017099

4.2.12 WC: 191694 have been practicing it. If the past is the best predictor of the future, then I also have some ideas about what changes we might anticipate in the law over the next half century. Oliver Wendell Holmes urged his young colleagues to “live the passion of your times.” I have followed that advice and now wish to share this passion with my readers. 12 HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_017099

Sponsored

Page 13 - HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_017100

4.2.12 WC: 191694 Part I: From Brooklyn to Cambridge (with stops in New Haven and Washington) Chapter 1: Born and religiously educated in Brooklyn The doctor told my pregnant and anxious mother that she would give birth “first in September.” So when I was born on September 1, 1938, my mother thought the doctor was a genius. I was the first person in the history of my family to be born in a hospital. My maternal grandfather, an immigrant from Poland, wanted me to be born at home, because in Poland, there were rumors that Jewish babies were switched with Polish babies. To prevent this from happening to his grandchild, he stood guard over me at the baby room. Nevertheless, when I started to misbehave early in my life, he was convinced that the switch had taken place, despite me being—in my paternal grandmother’s words—“the spittin’ image” of my father. (I was well into my adult life before I realized that I was much more like my mother in ways other than physical resemblance.) I was born in the Williamsberg neighborhood of Brooklyn, where both of my parents had lived most of their lives, having moved as youngsters from the lower East Side of Manhattan where they were born to Orthodox Jewish parents who had emigrated from Poland at the end of the 19" and beginning of the 20" Century. When my mother was pregnant with my brother Nathan, who is three and a half years younger than me, we moved to the Boro Park neighborhood of Brooklyn where I grew up and where my parents remained until their deaths. Boro Park is unique among American Jewish neighborhoods in that it has always been Jewish. Unlike the neighborhoods of Manhattan—such as the Lower East side and Harlem, which have had changing ethnic populations—Boro Park has always been, and remains, dominantly Jewish. The first occupants of the small tract houses built near the beginning of the twentieth century of the site of rural farms were Jewish immigrants seeking to escape from the crowded ghettos of Manhattan and later Williamsberg. The current occupants of the modern multi-dwelling units are Chasidic Jews who have moved from Crown Heights and Williamsberg seeking to recreate the shtetles of Eastern Europe. When I lived in Boro Park during the 1940s and 1950s, it was a modern Orthodox community of second generation Jews whose grandparents had emigrated mostly from Poland and Russia during the late 19" and early 20" centuries. Following the end of World War II, some displaced persons who had survived the Holocaust moved into the neighborhood. My parents reached adulthood in Williamsberg during the peek of the Great Depression. My mother Claire had been a very good student at Eastern District High School and at the age of 16 enrolled at City College in the fall of 1929—the first in the history of her family to attend college. She was forced to leave before the end of the first semester by her father’s deteriorating economic situation. She went to work as a bookkeeper, earning $12 a week. My father, who was not a good student, attended a Yeshiva high school in Williamsberg. It was called Torah V’Daas—ttranslated as Bible and Knowledge. He began to work during high school and never attended college. 13 HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_017100

Page 14 - HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_017101

4.2.12 WC: 191694 My grandparents knew each other from the neighborhood even before my parents met. My grandfathers were both amateur “chazanim,” cantors, who sang the Jewish liturgy in small synagogues, called “shteebles.” They were slightly competitive, but were both involved in the founding of several Jewish institutions in Williamsberg, including a free loan society, a burial society, the Young Israel synagogue and the Torah V’Daas Yeshiva. Their day jobs were typical for their generation of Jewish immigrants. Louis Dershowitz, my paternal grandfather, sold corrugated boxes. Naphtali Ringel, my maternal grandfather, was a jeweler. My grandmothers, Ida and Blima, took care of their many children. Each had eight, but two of Blima’s children died of diphtheria during an epidemic. My mother nearly died during the influenza outbreak of 1917, but according to family lore, she was saved by being “bleeded.” I was born toward the end of the depression and exactly a year to the day before the outbreak of the Second World War. I was the first grandchild on both sides of my family. Many were to follow. Among my earliest memories were vignittes from the Second World War, which ended when I was nearly seven. I can see my father pasting on the Frigidaire door newspaper maps depicting the progress of allied troops toward Berlin. I can hear radio accounts, in deep Stentorian voices, from WOR (which I thought spelled “war’’) announcing military victories and defeats. I can still sing ditties I learned from friends (the first sung to the tune of the Disney song from Snow White). “Whistle while you work Hitler is a jerk Mussolini is a meanie And the Japs are worse” And another (sung to the melody of “My Country Tis of Thee, Sweet Land of Liberty”): “My country tis of thee Sweet land of Germany My name is Fritz My father was a spy Caught by the FBI Tomorrow he must die My name is Fritz.” The comic books we read during the war always pitted the superheroes against the “Nazis” and “Japs” and I wanted to help in the effort. I decided that if Billy Batson could turn into Captain Marvel by simply shouting Shazam, so could I. And so, after making a cape out of a red towel and tying it around my neck, I jumped out of the window yelling Shazam. Fortunately, I lived on the first floor and only sustained a scraped knee and a bad case of disillusionment. (For my 70" birthday, my brother found a card that commemorated the superhero phase of my life; it showed an elderly Superman standing on a ledge, ready to fly, but wondering “now where is it ’m supposed to be flying?”’) 14 HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_017101

Page 15 - HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_017102

4.2.12 WC: 191694 If I could help our war effort by turning myself into a superhero, at least I could look out for German spies on our beaches. When I was four years old, German spies landed on Long Island in a submarine. Although they were quickly captured, there were rumors of other planned landings. And so over the next few summers, which my family spent in a rented room near Rockaway Beach, a local police officer paid us kids a penny a day to be on the lookout for “Kraud Subs.” We took our job very seriously. I recall my grandmother Ringel (my mother’s mother), who was recovering from a heart attack, taking me to a rehabilitation home in Lakewood, New Jersey, where several wounded or shell- shocked soldiers were also being rehabilitated and listening to their scary combat stories. Then I remember, quite vividly, both VE (Victory in Europe) and VJ (Victory over Japan) days. There was dancing in the streets, block parties and prayerful celebrations. Our soldiers, including several of my uncles, were coming home. (My father received a medical deferment because he had an ulcer, which my mother said was caused by my bad behavior.) We weren’t told of any Holocaust or Shoah—those words were not even in our vocabulary—just that we had lost many relatives in Europe to the brutal Nazis and Hitler (“Yemach Sh’mo—may his name be erased from memory). We cheered Hitler’s death, which according to a Jewish joke of the time, we knew would occur on a Jewish holiday—because whatever day he died would be a Jewish holiday! A few weeks earlier, we cried over Roosevelt’s passing, which I heard of while listening to the radio and broke the news to my grandmother Ringel, who was taking care of me. She refused to believe it, until she herself heard it on the radio. Then she cried. Roosevelt (which she pronounced like “Rosenfeld”) was the hero of our neighborhood (and other Jewish neighborhoods). A magazine photo of him hung in our home. The “greenies” (recent immigrants, “greenhorns”) who moved to Boro Park from the displaced person camps never talked out what had happened “over there.” The tattooed numbers on their arms remained unexplained, though we knew they were the dark reminders of terrible events. Among my other early memories was Israel’s struggle for independence and statehood, just a few years after the war. My family members were religious Zionists (“Misrachi Zionists”). We had a blue and white Jewish National Fund “pushka” (charity box) in our homes, and every time we made a phone call, we were supposed to deposit a penny. We sang the “Jewish National Anthem” (Hatikvah) in school assemblies. I still remember its original words, before Israel became a state: “Lashuv L’Eretz Avosainv” (“to return to the land of our ancestors’). One particular incident remains a powerful and painful memory. My mother had a friend from the neighborhood named Mrs. Perlestein, whose son Moshe went off to fight in Israel’s War of Independence. There was a big party to celebrate his leaving. Several months later, I saw my mother crying hysterically. Moshe had been killed, along with 34 other Jewish soldiers and civilians, trying to bring supplies to a Jewish outpost near Jerusalem. My mother kept sobbing, “She was in the movies, when her son was killed. She was in the movies.” Israel’s war had come home to Boro Park. It had been brought into our own home. Everyone in the neighborhood knew Moshe and his parents. He had attended my elementary school, played stickball on my be) HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_017102

Sponsored

Page 16 - HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_017103

4.2.12 WC: 191694 block and was a local hero. It was a shared tragedy and Moshe’s death—combined with my mother’s reaction to it—had a profound and lasting effect on my 9 year old psyche. My friends and I formed a “club’”—teally just a group of kids who played ball together. We named it “The Palmach”—after the Israeli strike force that was helping to win the war. We memorized the Palmach Anthem “Rishonin, Tamid Anachnu Tamid, Anu, Anu Hapalmach.” ( “We are always the first, we are the Palmach”). Recently, I spoke to a Jewish group in Los Angeles and among the guests were Vidal Sassoon (the style master) and David Steinberg (the comedian). Steinberg mentioned to me that when Sassoon was a young man, he had volunteered to fight for the Palmach (If you think that seems unlikely, consider that “Dr. Ruth” Westheimer served as a sniper in the same war). I challenged Sassoon to sing the Palmach Anthem and before you knew it, Sassoon and I were loudly belting out the Hebrew words to the amusement of the other surprised guests. Israel declared statehood in May of 1948, when I was nine and a half years old. Following its bold declaration that after 2,000 years of exile, there arose a Jewish state in the Land of Israel, (supported by the United Nations, the United States, the Soviet Union and most western nations), the nascent state was attacked by the armies of the surrounding Arab countries. That summer I went to a Hebrew speaking Zionist summer camp called “Massad.” During my summer at Camp Massad (where the counselor of an adjoining bunk was a young Noam Chomsky, then a fervent left-wing Zionist) we heard daily announcements over the loudspeaker regarding the War of Independence. We sang Israeli songs, danced the hora and played sports using Hebrew words (a “strike” was a “Shkeya,” a “ball” a “kadur”.) The announcement I remember most vividly was “Hatinok Rut met hayom’”—the “babe” Ruth died today. But I also remember several announcements regarding the death or wounding of Israelis who were related to the people in the camp. One out of every hundred Israeli men, women and children were killed—some in cold blood, after surrendering—while defending their new state. Many of those killed had managed to survive the Holocaust. We also learned of Stalin’s campaign against Jewish writers, politicians and Zionists. After the end of the war, Stalin became the new Hitler as we read about show trials, pogroms and executions of Jews. We hated communism almost as much as we hated fascism. These early memories—relating to the America’s war against Nazism, Israel’s War of Independence, and Stalin’s war against the Jews—contributed significantly to my emerging ideology and world views. I grew up in a home with few books, little music, no art, no secular culture and no intellectualism. My parents were smart but had no time or patience for these "luxuries." Our home was modest--the ground floor of a two and half family house. (The finished basement was rented to my cousin and her new husband). Our apartment had two small bedrooms, the smaller of which I shared with my brother. We ate in the kitchen. The living room, which had the mandatory couch covered with a plastic protector, was reserved for special guests (who were rare). The tiny bathroom was shared by the four of us. The foyer doubled as a dining area for Friday night and Shabbat meals. The total area was certainly under __ square feet. But we had an outside—and what an outside it was! In the front there was a small garden and a stoop. In the 16 HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_017103

Page 17 - HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_017104

4.2.12 WC: 191694 rear there was a tiny back porch, a yard and a garage. Since we had no car, we rented the garage to another cousin who used it to store the toys he sold wholesale. We were not poor. We always had food. But we couldn’t afford any luxuries, such as restaurants. We passed down clothing from generation to generation and ate a lot of “leftovers”. (Remember the comedian who said “we always ate leftovers—nobody has ever found the “original” meal.) My mother has always said we were “comfortable.” (The same comedian told about the Jewish man who was hit by a car, and was laying on the ground; when the ambulance attendant asked him “are you comfortable,” he replied, “I make a living.’’) The center of our home was the stoop in front of the house. We sat on it, played stoop ball on it, jumped from it and slid down the smooth slides on each side of it. It was like a personal playground. On nice days, everyone was outside, especially before the advent of television. We even listened to the radio--Brooklyn Dodger baseball games, the Lone Ranger, "Can You Top This?," "The Shadow," "Captain Midnight," and "The Arthur Godfrey Show"--while sitting on the stoop, with the radio connected to an inside socket by a long, frayed extension cord. We ate lunch on the stoop on days off from school, had our milk and cookies on the stoop when we got back from school, traded jokes, and even did our homework on the stoop. Mostly, we just sat on the stoop and talked among ourselves and to passing neighbors, who knew where to find us. In those days, nobody called ahead—phone calls were expensive. They just dropped by. In front of the stoop was what we called "the gutter." (Today it is referred to as "the street.") The gutter was part of our playground since cars rarely drove down our street. We played punch ball in the gutter, stickball in the driveway and basketball in front of the garage--shooting at a rim screwed to an old ping pong table that was secured to the roof of the garage by a couple of two by fours. We had no room to play indoors, so we had to use the areas around the house as our play area. Our house became the magnet for my friends because we had a stoop, a hoop and an area in front of our stoop with few trees to hinder the punched ball. (A ball that hit a tree was called a “hindoo”—probably a corruption of “hinder.’’) The stereotype of the Brooklyn Jewish home during the immediate post WWII era was one filled with great books, classical music, beautiful art prints and intellectual parents forcing knowledge into their upwardly mobile male children aspiring to become doctors, teachers, lawyers and businessmen. (The daughters were also taught to be upwardly mobile by marrying the doctors, etc.) My home could not have been more different--at least externally. The living room book shelves were filled with inexpensive knickknacks (chachkas). The only books were a faux leather yellow dictionary that my parents got for free by subscribing to "Coronet Magazine." When I was in college, they briefly subscribed to the Reader's Digest Condensed Books. There was, of course, a "Chumash" (Hebrew bible) and half dozen prayer books (siddurs and machsers). I do not recall 17 HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_017104

Page 18 - HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_017105

4.2.12 WC: 191694 seeing my parents read anything but newspapers (The New York Post), until I went to college. They were just too busy making a living--both parents worked--and keeping house. There were no book stores in Boro Park, expect for a small used book shop that smelled old and seemed to specialize in subversive books. The owner, who smelled like his mildewed books, looked like Trotsky, who he was said to admire. We were warned to stay away, lest we be put on some "list" of young subversives. My parents, especially my mother, were terrified about “lists” and “records.” This was, after all, the age of “blacklists,” “redchanels,” and other colored compilations that kept anyone on them from getting ajob. “They will put you on a list,” my mother would warn. Or “it will go on your permanent record.” When I was 13 or 14, I actually did something that may have gotten me on a list. It was during the height of the McCarthy period, shortly after Julius and Ethel Rosenberg had been sentenced to death. A Rosenberg relative was accosting people getting off the train, asking them to sign a petition to save the Rosenbergs’ lives. I read the petition and it made sense to me, so I signed it. A nosy neighbor observed the transaction and duly reported it to my mother. She was convinced that my life was over, my career was ruined and that my willingness to sign a communist-inspired petition would become part of my permanent record. (Was there ever really a permanent record? It was certainly drummed into me for years that such a paper existed. I'd love to find mine and see what’s in it.)'? My mother decided that I had to be taught a lesson. She told my father the story. I could see that my father was proud of what I had done, but my mother told him to slap me. Ever obedient, he did, causing him more pain than me. In addition to the “subversive” book store, we had a library that was also tiny and somewhat decrepit, but when I was nearing the end of high school, a new, spacious library opened about half a mile away. We went there every Friday afternoon--for two reasons. First, that's where the girls were on Friday afternoon. And second, we could take out up to four books and keep them for a month. The two reasons merged when Artie Edelman realized that we could impress the girls by taking out serious books. Up until that time my reading of serious literature had been limited to Classic Comics. Don't laugh! Classic Comics were marvelous. Not only could we read about the adventures of Ivanhoe, we could see what he looked like! My first erotic desires were aroused by the illustration of the dark- haired "Jewess" Rebecca. (I can still picture her and have searched for a copy of the Classic Comic at flea markets from coast to coast to relive my unrequited adolescent lust). I recently came across the Classic Comic of Crime and Punishment. Having read three translations of the great work of Dostoyevsky, I was amazed at how faithful the comic was to the tone, atmosphere and even words of the original. I tried to give it to my granddaughter who was reading the book for class, but she politely turned down the offer, with a slight air of condescension that one gratefully accepts only from a grandchild. '° Now there really are “permanent records.” They’re called Facebook, Twitter and the Internet. 18 HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_017105

Sponsored

Page 19 - HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_017106

4.2.12 WC: 191694 The first real books I actually read were several to which I had been introduced by the Classic Comics: The Count of Monte Christo, The Red Badge of Courage; Moby Dick; and a Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur's Court. During my senior year in high school, I became a voracious reader, to the disdain of some family members. My Uncle Hedgie (a nickname for Harry) would berate me for sitting around the house reading, when I could be working or playing sports. "Be a man," he would demand. "Get off your ass." But I would stay in my tiny room, with my Webcote tape recorder playing classical music I had recorded off WQXR, the New York Times classical music station, or off a record I borrowed from the library and recorded from my friend Artie's turntable. I also bought a used copy of the Encyclopedia Americana, whose twenty plus volumes filled the hitherto empty shelves in our living room. My friend Norman Sohn had found an old book store in Manhattan that sold used Encyclopedias, and the Americana cost only $75, as contrasted with the Britannica, which was $200. During my early years, all we had was a small plastic radio that lived in the kitchen, unless it was moved near the stoop. When I was 10 years old, we bought a ten inch TV "console" that included a 78 phonograph player that opened at the top. But my mother had situated her "good" lamp on the top of the console, so I couldn't get access to the turntable. I saved up, and with my Bar Mitzvah money, I bought a humongous webcore reel to reel tape recorder, which must have been a foot cubed. I could barely lift it, and the tape often tangled or split, but it was better than the wire recorder technology that it replaced. I loved classical music, especially opera and choral music. As an adolescent I had sung alto in the local synagogue choir and had a fairly good voice. I was "fairly" good--but not very good-- at lots of things in addition to singing: athletics, acting, joke telling and getting dates with girls. I was very good at only one thing: debating. And I was equally bad at one thing: school. My passion for music took me to the Metropolitan Opera House, where for 50 cents, a student could get a seat with a table and a lamp if he came with a score of the opera. We would borrow the score from the library, take a train to Times Square and listen to Richard Tucker, Robert Merrill, Jan Pierce and Roberta Peters sing Carman, La Boheme and La Traviata. (We were forbidden to listen to Wagner, because he was an anti-Semite, who admired). I also became passionate about art. All kinds of art from Egyptian and Roman Sculpture to Picasso's Guernica and Rodan's Thinker. There were no art poster or reproductions in our home. The walls had mirrors (to make the apartment seem bigger) and some family photos. But there were free museums all around us, and the library had art books--with pictures of naked women! I loved Goya's nude, especially when contrasted with the clothed version of La Gioconda who I could imagine undressing just for me! The girls loved to be asked on a museum date, and we loved to ask because it was free and it showed them that we had "culture" (pronounced "culchah"). 19 HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_017106

Page 20 - HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_017107

4.2.12 WC: 191694 To this day I have no idea how I fell in love with literature, music and art. They are my passions, as they have been since I was old enough to appreciate these "Iuxuries"--inexpensive as they were to us--that my parents couldn't afford. I was never exposed to classical music or art, even in school where the music teacher taught us "exotic" songs like “finicula, funicula,” American songs by Stephen Foster, and an assortment of religious and Zionist Hebrew songs. (Zum Gali, Gali, Gali; Tsena, Tsena; Hayveynu Shalom Alechem.) Our art teachers tried to teach us to draw “useful” objects, like cars, trains and horses. My friends’ homes were as barren of culture as mine with the exception of Artie Edelman and Bernie Beck, whose parents were better educated and more cultured than mine. I must have picked up some appreciation of music and art from them. When I went to sleep away camp, especially as a junior counselor, I also came in contact with music and art through the “rich” Manhattan kids who had attended the expensive camp as paying campers and were now junior counselors. Several of them, who became my friends, had been exposed to culture through their more sophisticated Jewish parents. None of these peripheral contacts with culture fully explains my transition from a home barren of books, records and posters, to my home as an adult that is filled with books, music, paintings, sculpture and historical objects." Nor does it explain why none of my three children, who were brought up in my home, have any real passion for the classical arts. They are by no means uncultured. They love popular music, films, current fiction, theater and gourmet food. But they don’t have the same passion for classical music or fine art that I have. By mentioning this difference, I don’t mean to be a snob, but for someone who strongly believes in the power of nurture, exposure and experience, this generational skip poses a dilemma. Reaction is, of course, one sort of experience, and my passion may well have been a reaction to my parents, as my childrens’ lack of passion for what moves me so deeply may be a reaction to their parents. So be it. The family values that shape my upbringing focused on modern Orthodox Judaism, religious Zionism, political liberalism of the sort represented by FDR, Anti-Nazism, Anti-Communism, opposition to all kinds of discrimination, support for freedom of speech, a hatred of McCarthyism, opposition to the death penalty, a commitment to self defense and defense of family and community, a strong sense of patriotism, and a desire to be as truly American as was consistent with not assimilating and losing our traditions and heritage. My father, who was a physically strong but rather meek man, wanted me to be “a tough Jew” who always “fought back.” He urged me to never let “them” get away with “it.” By them he meant anti-Semites, and by it, he meant pushing Jews around. He taught me to box and wrestle and insisted that I never “tattle” on my friends, regardless of the consequences to me. One of my father’s brother’s was a man named Yitzchak, who we called Itchie. It had nothing to do with any skin condition. One day my Uncle Itchie took me to a Brooklyn Dodger baseball " Finding Jefferson 20 HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_017107

Page 21 - HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_017108

4.2.12 WC: 191694 game that got rained out half way through. We ran to the train station only to find no one tending the token booth. My uncle had one token and so the two of us squeezed through the turnstile on his one token. As soon as we got home he took a dime, put it in an envelope and sent it to the transit authority, apologizing profusely for temporarily cheating them of their dime. A year later he did the same thing, but on a much larger scale. My Uncle Itchie stowed away on a ship headed for Palestine in order to participate in Israel’s struggle for statehood. He did not have enough money for passage, so he hid in a closet during the nearly month long trip, getting food from a friend who was paying his own way over. My Uncle then swam from the ship to shore, evading British authorities. After working for several months he then sent the full fare for the lowest class of service to the shipping company. Those were the values with which I was brought up. You do what you have to do, but then you pay your debts. Religion in my home was not a matter of faith or an accepted theology. To this day, I have no idea what my parents believed about the nature of God, the literal truth of the Bible, heaven and hell, or other issues so central to most religions. Ours was a religion of practice and rules—of required acts and omissions. A cartoon I once saw perfectly represented my parents approach to religion. It showed a father dragging his reluctant young son in the direction of the synagogue and saying: “Atheist, Shmathiest, I don’t care—as long as you come to shul.” Our Judaism was entirely rule bound. Before every activity, there was a required “brucha”—a formulistic blessing appropriate to the activity. “Baruch ata Adonoy”—“blessed be you our God”—followed by a reference to His creation: “who brings forth bread from the earth” or “wine from the grapes” or “fruit from the trees” or “produce from the ground.” Then there was a generic brucha that covered everything not included among the specific blessing: “Sheh-hakol Nihiye B’Dvaroh.” My grandmother Ringel, who was the religious enforcer in the family, would ask demandingly, if she saw me drinking a glass of water, “Did you make a “shakel,” referring to the previously mentioned generic blessing. My grandmother, who spoke no Hebrew, probably had no idea of the literal meaning of the blessing, but she knew—and insisted that I knew—you had to recite it (even just mumble it) before you drank the water. There were rules for everything. If you accidentally used a “milichdika” (dairy) fork on a “flayshidika” (meat) item, the offending (or offended) item had to be buried in the earth for exactly seven days. That restored its kosher quality by “kashering” it. After eating meat, we had to wait precisely 6 hours before eating dairy—after eating dairy, however, you had to wait only half an hour to eat meat, but a full hour if the “dairy” meal contained fish. Not a minute less. When my parents told me the rules of swimming after eating—wait two hours after a heavy meal, one hour after a light meal, half an hour after a piece of fruit and 15 minutes after a Hershey bar—lI thought these were religious rules, because they paralleled the rules about how long you had to wait between meat and dairy. (I later learned that the swimming rules were based neither on religion, nor upon science, but rather on questionable “folk wisdom.”) From my earlier days, I accepted the highly technical, rule-oriented religious obligations imposed on me by my parents and grandparents. It was a lot easier for me to obey rules—even if I didn’t understand the reasons, if any, behind them—than to accept a theology that was always somewhat Al HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_017108

Sponsored

Page 22 - HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_017109

4.2.12 WC: 191694 alien to my rational mindset. (And I suspect, to my parents, if they even bothered to think about it.) Everyone in the almost entire Jewish neighborhood (at least everyone who was part of the modern Orthodox community) followed the rules. Few, I suspect, accepted the entire theological framework that included the literal truth of the bible, the resurrection of the dead, heaven and hell (which were not in the Jewish Bible) and the incorporeal nature of a single God. What we cared about was the precise ingredients in a candy bar (no lard or gelatin), the number of steps you could take if your yarmulkah fell off (more on this later), whether you could wear your house key as a tiepin to avoid the prohibition against carrying on the Sabbath, whether it was permissible to use an automatic timer—a “shabos clock”—to turn on the TV for a Saturday afternoon World Series game, or whether you could ride on an elevator on Shabos if it automatically stopped on every floor and required no pressing of buttons. The rabbis answered these questions for us, but they didn’t always agree. My mother had little patience with most of the local rabbis because her late father, who was not a rabbi, “knew so much more than they did,” and always resolved religious disputes by accepting the approach that was “easiest” and most adaptive to the modern lifestyle. Even my grandmother knew more than these “phony rabbis,” my mother would insist contemptuously. My mother always said, “Respect people, not titles.” Then she was appalled when I showed disrespect for my frequently incompetent teachers! Most of the rules we were required to obey were negative ones: “Donts.” Don’t—eat unkosher, drive or work on Shabas, eat anything on fast days, marry a non-Jew, eat ice cream after a hot dog, wear leather on Yom Kippur, talk after washing your hands but before making a “motzie” and eating the challah. My grandmother—the enforcer—had a favorite Yiddish word: “meturnished’”—tt is forbidden to do! She would shout it out in anticipation of any potential violation. If she saw you about to eat a Nabisco cookie, she would intone the M word. If she saw you putting a handkerchief in your pocket on Shabas, the word would ring in your ear. If you even thought about putting your yalmulkah in your pocket, you would hear the word. Once I began to whistle a tune. My musical effort was grated with a loud “meturnished.” “Why?” I implored. There’s nothing in the Torah about whistling. “It is unJewish,” my grandmother insisted, “The Goyim whistle, we don’t.” It’s now more than 30 years, since Grandma Ringel died, but the M word still rings in my ears every time I indulge in a prohibited food or contemplate an un-Jewish activity (such as enjoying a Wagnerian opera). Freud called it the “superego.” He must have had a Jewish grandmother too. Of course we tried to figure out ways around these prohibitions—half of Jewish law seems to be creating technical prohibitions, while the other half seems to be creating ways around them. Much like the Internal Revenue Code. No wonder so many Jews become lawyers and accountants. It’s not in our DNA; it’s in our religious training. A story from my earliest childhood illustrates the extraordinary hold that religion—really observance of religious obligations—held over all of us. A few months before my brother was born, my father was holding my hand on a busy street, while my mother was shopping. She had just bought me a new pair of high leather shoes—they went above my ankles. For some reason, I bolted away from my father and ran into the “gutter.” My foot was run over by an 18 wheeler truck. It would have been much worse had my father not 22 HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_017109

Page 23 - HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_017110

4.2.12 WC: 191694 pulled me out from under the humongous vehicle. Fortunately, the new shoes saved my foot from being crushed, but several bones were broken and I was rushed to the nearest hospital, which was Catholic. My parents left me there overnight. At about 8:00PM one of the nurses called my mother and said that I was refusing to eat and demanding to go to Florida. My mother said, “He’s never even heard of Florida.” She was told to come to the hospital immediately. She saw me sitting in front of my tray of food refusing to eat and screaming, “Miami, Miami!” To the nurses, that referred to a city in southern Florida. My mother immediately understood that I was referring not to Miami, but to my “yami’”—which was short for yamulka, the religious skullcap that every Jewish male must wear while eating. I refused to eat without my yami, even though I was only 3 years old. My response was automatic—programmed. As soon as my mother made a yamulka for me out of a handkerchief and placed it on my head, I ate all the food and asked for doubles (the Catholic hospital provided kosher food for Jewish patients.) I’m sure I mumbled the appropriate Bruchas for each item of food I imbibed. We learned these rules first at home and then in the Yeshiva—Jewish day school—that nearly everyone in the neighborhood attended. As is typical in Orthodox Jewish neighborhoods, there were two competing Yeshivas: One taught Yiddish, the other Hebrew. I started out in the Yiddish-speaking more traditional, school-named “Torahs Emes” (the Truthful Bible), where my grandma Ringel wanted me to go to learn the “Mamma Loshen’”—the mother tongue. But after two years, my parents switched me to the Hebrew-speaking, more modern Yeshiva, named “Etz Chaim” (the Tree of Life), which I attended through 8" grade, when I shifted to a Yeshiva high school until I finished 12 grade. My Yeshiva education was a decidedly mixed blessing (both in the literal and figurative senses of that overworked phrase.) The hours were long: elementary school went from 8:30AM to 4:30PM; high school from 9:00AM to 6:10PM. We had only one full day off, Saturday, but it really wasn't a day off, since we spent much of it in the synagogue--9:00AM to noon and then afternoon and evening services, which varied in time depending on when it got dark (two stars had to be visible to the naked eye, or in the event there were clouds, "would have been" visible. ) Friday was an early day, with school ending at about 1PM to allow us to prepare for the Sabbath. And Sunday was also a half day, though this compromise with secularism engendered grumbling from some of the old fashioned rabbis, who wanted us to spend the entire Christian day of rest in class. Mornings were generally devoted to religious subjects—Bible (Tanach) Talmud, (Gemarah), ritual rules (Shulchan Aruch,) and ethics (Pirkay Avos.) Afternoons were devoted to the usual secular subjects--math, science, history, English, French (for the smart kids who wanted to become doctors) or Spanish (for the rest of us), (no German or Latin), civics, gym, art, music appreciation--as well as "Jewish secular" subjects, such as Hebrew, Jewish history, Zionism and Jewish literature. Then there was debate, student government, basketball and other "extracurricular" activities. Lunch "hour", which was 35 minutes, separated the religious from the secular classes and was the only time we ever discussed the conflict between what we were taught 23 HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_017110

Page 24 - HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_017111

4.2.12 WC: 191694 in the morning, such as the creation story, and what we were taught in the afternoon, such as evolution and genetics. No attempt was made to reconcile Torah (scripture) and Madah (secular knowledge). They were simply distinct and entirely separate world views (or as my late colleague Steven Jay Gould put it in his always elegant choice of words, "separate magisteria"). We lived by the rule of separation between church and state, and for most of the students it raised no issue of cognitive dissonance. In the morning, they thought like rabbis; in the afternoon like scientists; and there was no need to reconcile. It was like being immersed in a good science fiction novel or film: one simply accepted the premises and everything else followed quite logically. For a few of us, that wasn't good enough. I recall vividly our efforts to find--or contrive-- common ground. For some, this quest took them to wonder whether the God of Genesis could have created evolution. For them there was an abiding faith that both religion and science could both be right. For me, the common ground was an abiding conviction that both could be wrong-- or at least incomplete as an explanation of how we came to be. I was skeptical of both religion and science. Genesis, though elegant and poetic, seemed too simple. But so did evolution--at least the way we were taught it. The apparent conflict between religion and science did not move me to search for reconciliation. It moved me to search for doubts, for holes (not black ones, but grey ones), for inconsistencies not between religion and science--that was too easy--but rather within religious doctrine and within scientific "truth." I loved hard questions. I hated the easy answers often given, with a smirk of self-satisfaction by my religious and secular teachers. The mission of our modern Orthodox Yeshiva was to integrate us into the mainstream of American life while preserving our commitment to modern Orthodox Judaism. “Torah” and “Madah” were the two themes. Torah, which literally means bible, represented the religious component. Madah, which literally means knowledge, represented the secular component. They were thought to be reconcilable, though little explicit effort was directed at reconciling the very different world views implicit in the relatively closed system of Orthodox Judaism and the openness that is required to obtain real secular knowledge. When it came to culture, however, there was actually very little conflict, because becoming good Americans—including immersing ourselves in mainstream American culture—was part of the mission of our schools. Of course I hated anything the teachers tried to imbue in us, because with a few exceptions, they taught by rote and memorization. Although I was good at memorization, I rebelled against the authoritarianism implicit in religious teaching. As much as I hated my teachers, they hated me even more. I loved conflict, doubt, questions, debates and uncertainty. I expressed these attitudes openly, often without being called on. I was repeatedly disciplined for my “poor attitude.” My 6" grade report card, which I still have, graded me “unsatisfactory” in “deportment” and “getting along with others.” I received grades of D in “effort,” D in “conduct,” D in “achievement,” C in spelling, D in “respects the rights of others,” D in “comprehension,” C+ in geography and A in “speaks clearly.” One teacher even gave me an “unsatisfactory” in “personal hygiene.” My mother, who was meticulous about cleanliness and scrubbed me clean every day before school, complained. The teacher replied, “his body is clean, but his mind is dirty; he refuses to show respect to his rabbis.” 24 HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_017111

Sponsored

Page 25 - HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_017112

4.2.12 WC: 191694 To be sure, I was a mediocre Yeshiva student--actually I exaggerate: I was slightly worse than mediocre, once having actually received a grade of "Bayn Ani Minus," which literally means "mediocre minus." I couldn't even quite make it to mediocrity. At least I had something to which to aspire! When I was in sixth grade, the school decided to administer IQ tests to all the students. The school called my mother and said that I had gotten one of the highest scores. At first the rabbi thought I had cheated, but when he was persuaded that in fact I had a high IQ he decided to put me in the A class. We had a track system and the grades were divided into the A, B and C classes. I had always been in the C class. My mother was worried about me having to compete with all those smart kids, so she persuaded the principal to compromise and put me in the B class, where I remained, getting C’s until I graduated. I spent my four high school years in what was called "the garbage class," which focused more on discipline than learning. I had a well deserved reputation in both elementary and high school as a “bad kid”. My grades were low (except on state-wide standardized tests called the “regents,” which I always aced). My conduct, called “deportment,” was terrible. I was always getting into trouble because of my pranks, because I “talked back” and was “fresh” to teachers, because I questioned everything, because I didn’t show “respect,” and because I was a “wise guy.” This was the greatest gift—ok, I will even say "blessing"—of my Yeshiva education: To question everything and everyone. It was merely an unintended consequence of the Yeshiva method, and I was certainly not its only beneficiary or (according to the rabbis) its only failure. The Jewish characteristic of questioning is not a complete coincidence. It is a product of experiences, and surely the Yeshiva education--which juxtaposes religion and science with little explicit effort to reconcile these distinct approaches to the search for truth--is an element of these experiences, for at least some young Jews. It certainly was for me, and for that I will be eternally grateful. I also need to thank my local synagogue for helping me discover sex. To this day I am convinced that some higher authority built the benches at precisely the right height to introduce sexual feelings at precisely the right time. When Orthodox Jews pray, they shake back and forth while standing up. At a certain point in my life, the top of the bench in front of me, which had a curve on the top, was exactly parallel to my genitals while I stood in prayer. It was while shuckling back and forth in the synagogue that I experienced my first arousal. What then was my "take away" from Yeshiva? For me it has been a lifelong "belief" in the "certainty" of "doubt." For most of my classmates, the take away has been a lifelong belief in the certainty of certainty. Why the difference? Surely minor genetic disparities do not explain such a profound difference in world views. Nor does mere intelligence, since many of my “certain” classmates were brilliant. I think it was the environment underneath the roof of our homes. I came to Yeshiva ready to doubt. Although my parents were both strictly observant, relatively modern Orthodox Jews, they too were skeptics, especially my mother. Despite her lack of formal education and high culture, she was a cynic, always doubting, always questioning, though this became less apparent as she grew older and observed--to her chagrin--what she had actually transmitted to her children. She doubted while continuing to observe all the rituals. That was the 25 HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_017112

Page 26 - HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_017113