HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_012899 - HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_013267

Document HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_012899 is a government record from the House Oversight Committee consisting of 369 pages.

This document appears to be the first part of a book titled "Engineering General Intelligence" by Ben Goertzel, Cassio Pennachin, and Nil Geisweiller, along with the OpenCog team. It outlines a path to advanced Artificial General Intelligence (AGI) via embodied learning and cognitive synergy, reviewing conceptual issues related to intelligence and mind, and sketching an architecture called CogPrime. The document also touches on creating machines that advance beyond human level intelligence.

Key Highlights

- •The document is Part 1 of "Engineering General Intelligence" by Ben Goertzel et al.

- •It discusses a novel, integrative architecture for Artificial General Intelligence (AGI) called CogPrime.

- •The document includes futuristic speculations about strongly self-modifying AGI architectures.

Frequently Asked Questions

Books for Further Reading

Perversion of Justice: The Jeffrey Epstein Story

Julie K. Brown

Investigative journalism that broke the Epstein case open

Filthy Rich: The Jeffrey Epstein Story

James Patterson

Bestselling account of Epstein's crimes and network

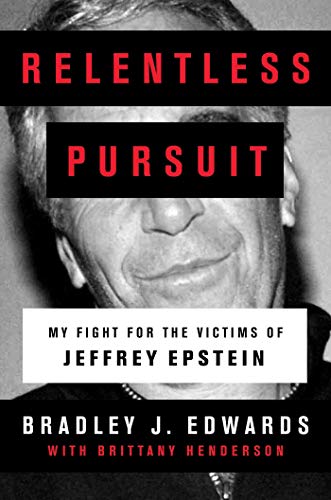

Relentless Pursuit: My Fight for the Victims of Jeffrey Epstein

Bradley J. Edwards

Victims' attorney's firsthand account

Document Information

Bates Range

HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_012899 - HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_013267

Pages

369

Source

House Oversight Committee

Date

September 19, 2013

Original Filename

EngGenInt_Vol_One.pdf

File Size

8.56 MB

Document Content

Page 1 - HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_012899

Ben Goertzel with Cassio Pennachin & Nil Geisweiller & the OpenCog ‘Team Engineering General Intelligence, Part 1: A Path to Advanced AGI via Embodied Learning and Cognitive Synergy September 19, 2013 HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_012899

Page 2 - HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_012900

HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_012900

Page 3 - HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_012901

This book 1s dedicated by Ben Goertzel to his beloved, departed grandfather, Leo Zwell — an amazingly warm-hearted, giving human being who was also a deep thinker and excellent scientist, who got Ben started on the path of science. As a careful experimentalist, Leo would have been properly skeptical of the big hypotheses made here — but he would have been eager to see them put to the test! HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_012901

Sponsored

Page 4 - HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_012902

HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_012902

Page 5 - HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_012903

Preface This is a large, two-part book with an even larger goal: To outline a practical approach to engineering software systems with general intelligence at the human level and ultimately beyond. Machines with flexible problem-solving ability, open-ended learning capability, creativity and eventually, their own kind of genius. Part 1, this volume, reviews various critical conceptual issues related to the nature of intel- ligence and mind. It then sketches the broad outlines of a novel, integrative architecture for Artificial General Intelligence (AGT) called CogPrime ... and describes an approach for giving a young AGI system (CogPrime or otherwise) appropriate experience, so that it can develop its own smarts, creativity and wisdom through its own experience. Along the way a formal theory of general intelligence is sketched, and a broad roadmap leading from here to human-level arti- ficial intelligence. Hints are also given regarding how to eventually, potentially create machines advancing beyond human level — including some frankly futuristic speculations about strongly self-modifying AGI architectures with flexibility far exceeding that of the human brain. Part 2 then digs far deeper into the details of CogPrime’s multiple structures, processes and functions, culminating in a general argument as to why we believe CogPrime will be able to achieve general intelligence at the level of the smartest humans (and potentially greater), and a detailed discussion of how a CogPrime-powered virtual agent or robot would handle some simple practical tasks such as social play with blocks in a preschool context. It first describes the CogPrime software architecture and knowledge representation in detail; then reviews the cognitive cycle via which CogPrime perceives and acts in the world and reflects on itself; and next turns to various forms of learning: procedural, declarative (e.g. inference), simulative and integrative. Methods of enabling natural language functionality in CogPrime are then discussed; and then the volume concludes with a chapter summarizing the argument that CogPrime can lead to human-level (and eventually perhaps greater) AGI, and a chapter giving a thought experiment describing the internal dynamics via which a completed CogPrime system might solve the problem of obeying the request “Build me something with blocks that I haven’t seen before.” The chapters here are written to be read in linear order — and if consumed thus, they tell a coherent story about how to get from here to advanced AGI. However, the impatient reader may be forgiven for proceeding a bit nonlinearly. An alternate reading path for the impatient reader would be to start with the first few chapters of Part 1, then skim the final two chapters of Part 2, and then return to reading in linear order. The final two chapters of Part 2 give a broad overview of why we think the CogPrime design will work, in a way that depends on the technical vil HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_012903

Page 6 - HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_012904

vili details of the previous chapters, but (we believe) not so sensitively as to be incomprehensible without them. This is admittedly an unusual sort of book, mixing demonstrated conclusions with unproved conjectures in a complex way, all oriented toward an extraordinarily ambitious goal. Further, the chapters are somewhat variant in their levels of detail — some very nitty-gritty, some more high level, with much of the variation due to how much concrete work has been done on the topic of the chapter at time of writing. However, it is important to understand that the ideas presented here are not mere armchair speculation — they are currently being used as the basis for an open-source software project called OpenCog, which is being worked on by software developers around the world. Right now OpenCog embodies only a percentage of the overall CogPrime design as described here. But if OpenCog continues to attract sufficient funding or volunteer interest, then the ideas presented in these volumes will be validated or refuted via practice. (As a related note: here and there in this book, we will refer to the "current" CogPrime implementation (in the OpenCog framework); in all cases this refers to OpenCog as of late 2013.) To state one believes one knows a workable path to creating a human-level (and potentially greater) general intelligence is to make a dramatic statement, given the conventional way of thinking about the topic in the contemporary scientific community. However, we feel that once a little more time has passed, the topic will lose its drama (if not its interest and importance), and it will be widely accepted that there are many ways to create intelligent machines — some simpler and some more complicated; some more brain-like or human-like and some less so; some more efficient and some more wasteful of resources; etc. We have little doubt that, from the perspective of AGI science 50 or 100 years hence (and probably even 10-20 years hence), the specific designs presented here will seem awkward, messy, inefficient and circuitous in various respects. But that is how science and engineering progress. Given the current state of knowledge and understanding, having any concrete, comprehensive design and plan for creating AGI is a significant step forward; and it is in this spirit that we present here our thinking about the CogPrime architecture and the nature of general intelligence. In the words of Sir Edmund Hillary, the first to scale Everest: “Nothing Venture, Nothing Win.” Prehistory of the Book The writing of this book began in earnest in 2001, at which point it was informally referred to as “The Novamente Book.” The original “Novamente Book” manuscript ultimately got too big for its own britches, and subdivided into a number of different works — The Hidden Pattern [Goe06a], a philosophy of mind book published in 2006; Probabilistic Logic Networks [GIGHO8], a more technical work published in 2008; Real World Reasoning [GGC" 11], a sequel to Proba- bilistic Logic Networks published in 2011; and the two parts of this book. The ideas described in this book have been the collaborative creation of multiple overlapping communities of people over a long period of time. The vast bulk of the writing here was done by Ben Goertzel; but Cassio Pennachin and Nil Geisweiller made sufficient writing, thinking and editing contributions over the years to more than merit their inclusion of co-authors. Further, many of the chapters here have co-authors beyond the three main co-authors of the book; and HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_012904

Sponsored

Page 7 - HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_012905

ix the set of chapter co-authors does not exhaust the set of significant contributors to the ideas presented. The core concepts of the CogPrime design and the underlying theory were conceived by Ben Goertzel in the period 1995-1996 when he was a Research Fellow at the University of Western Australia; but those early ideas have been elaborated and improved by many more people than can be listed here (as well as by Ben’s ongoing thinking and research). The collaborative design process ultimately resulting in CogPrime started in 1997 when Intelligenesis Corp. was formed — the Webmind AI Engine created in Intelligenesis’s research group during 1997-2001 was the predecessor to the Novamente Cognition Engine created at Novamente LLC during 2001-2008, which was the predecessor to CogPrime. Acknowledgements For sake of simplicity, this acknowledgements section is presented from the perspective of the primary author, Ben Goertzel. Ben will thus begin by expressing his thanks to his primary co-authors, Cassio Pennachin (collaborator since 1998) and Nil Geisweiller (collaborator since 2005). Without outstandingly insightful, deep-thinking colleagues like you, the ideas presented here — let alone the book itself— would not have developed nearly as effectively as what has happened. Similar thanks also go to the other OpenCog collaborators who have co-authored various chapters of the book. Beyond the co-authors, huge gratitude must also be extended to everyone who has been involved with the OpenCog project, and/or was involved in Novamente LLC and Webmind Inc. before that. We are grateful to all of you for your collaboration and intellectual companionship! Building a thinking machine is a huge project, too big for any one human; it will take a team and I’m happy to be part of a great one. It is through the genius of human collectives, going beyond any individual human mind, that genius machines are going to be created. A tiny, incomplete sample from the long list of those others deserving thanks is: e Ken Silverman and Gwendalin Qi Aranya (formerly Gwen Goertzel), both of whom listened to me talk at inordinate length about many of the ideas presented here a long, long time before anyone else was interested in listening. Ken and I schemed some AGI designs at Simon’s Rock College in 1983, years before we worked together on the Webmind AI Engine. Allan Combs, who got me thinking about consciousness in various different ways, at a very early point in my career. I’m very pleased to still count Allan as a friend and sometime collaborator! Fred Abraham as well, for introducing me to the intersection of chaos theory and cognition, with a wonderful flair. George Christos, a deep AI/math/physics thinker from Perth, for re-awakening my interest in attractor neural nets and their cognitive implications, in the mid-1990s. e All of the 130 staff of Webmind Inc. during 1998-2001 while that remarkable, ambitious, peculiar AGI-oriented firm existed. Special shout-outs to the "Voice of Reason" Pei Wang and the "Siberian Madmind" Anton Kolonin, Mike Ross, Cate Hartley, Karin Verspoor and the tragically prematurely deceased Jeff Pressing (compared to whom we are all mental midgets), who all made serious conceptual contributions to my thinking about AGI. Lisa Pazer and Andy Siciliano who made Webmind happen on the business side. And of course Cassio Pennachin, a co-author of this book; and Ken Silverman, who co-architected the whole Webmind system and vision with me from the start. HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_012905

Page 8 - HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_012906

The Webmind Diehards, who helped begin the Novamente project that succeeded Webmind beginning in 2001: Cassio Pennachin, Stephan Vladimir Bugaj, Takuo Henmi, Matthew Ikle’, Thiago Maia, Andre Senna, Guilherme Lamacie and Saulo Pinto Those who helped get the Novamente project off the ground and keep it progressing over the years, including some of the Webmind Diehards and also Moshe Looks, Bruce Klein, Izabela Lyon Freire, Chris Poulin, Murilo Queiroz, Predrag Janicic, David Hart, Ari Heljakka, Hugo Pinto, Deborah Duong, Paul Prueitt, Glenn Tarbox, Nil Geisweiller and Cassio Pennachin (the co-authors of this book), Sibley Verbeck, Jeff Reed, Pejman Makhfi, Welter Silva, Lukasz Kaiser and more All those who have helped with the OpenCog system, including Linas Vepstas, Joel Pitt, Jared Wigmore / Jade O'Neill, Zhenhua Cai, Deheng Huang, Shujing Ke, Lake Watkins, Alex van der Peet, Samir Araujo, Fabricio Silva, Yang Ye, Shuo Chen, Michel Drenthe, Ted Sanders, Gustavo Gama and of course Nil and Cassio again. Tyler Emerson and Eliezer Yudkowsky, for choosing to have the Singularity Institute for AI (now MIRI) provide seed funding for OpenCog. The numerous members of the AGI community who have tossed around AGI ideas with me since the first AGI conference in 2006, including but definitely not limited to: Stan Franklin, Juergen Schmidhuber, Marcus Hutter, Kai-Uwe Kuehnberger, Stephen Reed, Blerim Enruli, Kristinn Thorisson, Joscha Bach, Abram Demski, Itamar Arel, Mark Waser, Randal Koene, Paul Rosenbloom, Zhongzhi Shi, Steve Omohundro, Bill Hibbard, Eray Ozkural, Brandon Rohrer, Ben Johnston, John Laird, Shane Legg, Selmer Bringsjord, Anders Sandberg, Alexei Samsonovich, Wlodek Duch, and more The inimitable "Artilect Warrior" Hugo de Garis, who (when he was working at Xiamen University) got me started working on AGI in the Orient (and introduced me to my wife Ruiting in the process). And Changle Zhou, who brought Hugo to Xiamen and generously shared his brilliant research students with Hugo and me. And Min Jiang, collaborator of Hugo and Changle, a deep AGI thinker who is helping with OpenCog theory and practice at time of writing. Gino Yu, who got me started working on AGI here in Hong Kong, where I am living at time of writing. As of 2013 the bulk of OpenCog work is occurring in Hong Kong via a research grant that Gino and I obtained together e Dan Stoicescu, whose funding helped Novamente through some tough times. e Jeffrey Epstein, whose visionary funding of my AGI research has helped me through a number of tight spots over the years. At time of writing, Jeffrey is helping support the OpenCog Hong Kong project. Zeger Karssen, founder of Atlantis Press, who conceived the Thinking Machines book series in which this book appears, and who has been a strong supporter of the AGI conference series from the beginning My wonderful wife Ruiting Lian, a source of fantastic amounts of positive energy for me since we became involved four years ago. Ruiting has listened to me discuss the ideas contained here time and time again, often with judicious and insightful feedback (as she is an excellent AI researcher in her own right); and has been wonderfully tolerant of me diverting numerous evenings and weekends to getting this book finished (as well as to other AGl-related pursuits). And my parents Ted and Carol and kids Zar, Zeb and Zade, who have also indulged me in discussions on many of the themes discussed here on countless occasions! And my dear, departed grandfather Leo Zwell, for getting me started in science. HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_012906

Page 9 - HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_012907

x1 e Crunchkin and Pumpkin, for regularly getting me away from the desk to stroll around the village where we live; many of my best ideas about AGI and other topics have emerged while walking with my furry four-legged family members September 2013 Ben Goertzel HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_012907

Sponsored

Page 10 - HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_012908

HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_012908

Page 11 - HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_012909

Contents 1 WWtFGAUWCHION » pci ms mimes emims emis Mews Hs EE ws ERE ws EE ws EES Ew KEE Eom 1 1.1 AT Returns to Its Roots ......... 0.00 eee eta 1 1.2 AGI versus Narrow AI ....... 000.0000 teens 2 1.3 CogPrime 2.0.0.0... teen etn teen teens 3 LA The Sée@et SAUCE :a:es emses cuee@s Emdes dE SMES MEME SOEMS SUEMS EME!s tweed ee 3 1.5 Esxtraordinary Proof? + csins caine cae us a3 ou ems CHEE CREE ORES REE RES wR 4 1.6 Potential Approaches to AGI ..........0..0..0 00. ec tee 6 1.6.1 Build AGI from Narrow Al ..........00.0000 20000 6 1.6.2 Enhancing Chatbots ..........0 00.00 ccc eee eee 6 1:6:8 Emulating the Brain,s casas caus os ewams yams Abs BRS BREE BREWS Bae 6 1.6.4 Evolve an AGI... 2... tenes 7 1.6.5 Derive an AGI design mathematically................0....0.2.00000. 7 1.6.6 Use heuristic computer science methods ............0. 0 ccc cece eee 8 1.6.7 Integrative Cognitive Architecture ............0.0020 000 e eee eee 8 1.6.8 Can Digital Computers Really Be Intelligent? .....................-0. 8 1.7 Five Key Words ........ 00.000: c cece ene teeta 9 1.7.1. Memory and Cognition in CogPrime ................ 000.00 eee eee 10 1.8 Virtually and Robotically Embodied AI ............ 0.0.0: cece ee eee 11 1.9 Language learning: sss animes am ems Oem SMS EMERG THES CRED PERS BOERS URES ae 12 1.10 AGI Ethics 2.0.0... ee ene nent ene ae 12 1.11 Structure of the Book .............0 00002 tee 13 1.12 Key Claims of the Book ......... 00.0... 13 Section I Artificial and Natural General Intelligence 2 What Is Human-Like General Intelligence? ...........................000. 19 Ql Introduction, asus cama ue ems oe ems UE RS BR EMSRS CRESS EAERS FAERIE BAERS BAERS BiH 19 2.1.1 What Is General Intelligence? ......... 0.0.00. eee 19 2.1.2 What Is Human-like General Intelligence? ......................0.0005 20 2.2 Commonly Recognized Aspects of Human-like Intelligence ................... 20 2.3 Further Characterizations of Humanlike Intelligence .....................-.. 24 2.3.1 Competencies Characterizing Human-like Intelligence ................. 24 2.3.2 Gardner’s Theory of Multiple Intelligences........................--. 25 xili HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_012909

Page 12 - HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_012910

xiv Contents 2.3.3 Newell’s Criteria for a Human Cognitive Architecture ................. 26 2.3.4 intelligence and Creativity ........0 0.000 c cee ce eee ee eee 26 2.4 Preschool as a View into Human-like General Intelligence.................... 27 2.4.1 Design for an AGI Preschool.......... 0.0.0 ee eee 28 2.5 Integrative and Synergetic Approaches to Artificial General Intelligence ....... 29 2.5.1 Achieving Humanlike Intelligence via Cognitive Synergy ............... 30 A Patternist Philosophy of Mind .....................0 2.00.0 cece eee 35 3.1 Introduction ........ 00.000 ce tenet nee ee 35 3.2 Some Patternist Principles...........000..0 0000 ec tenes 35 3d COSRIIVE SYPETEY a: ws coe ws cmems mews Ca we ws Swe w Ss Swe w Ss EME ws EME mS MES Hom 40 3.4 The General Structure of Cognitive Dynamics: Analysis and Synthesis ........ 42 3.4.1 Component-Systems and Self-Generating Systems.................... 42 3.4.2 Analysis and Synthesis........ 0.0.0. c eee eee eee 43 3.4.3 The Dynamic of Iterative Analysis and Synthesis .................... 46 3.4.4 Self and Focused Attention as Approximate Attractors of the Dynamic of Iterated Forward-Analysis .......0.0.. 00000: cece eee eee eee AT 3.4.5 Conclusion ......... 000002 50 3.5 Perspectives on Machine Consciousness........0..000 000 cece eee eee eee 51 3.6 Postscript: Formalizing Pattern ......... 0000. cee tees 53 Brief Survey of Cognitive Architectures .................. 0.00. cee ee eee eee 57 4.1 Introduction ..........0.0. 000 0c eee eee ee 57 4.2 Symbolic Cognitive Architectures.........000 0.0 cece eee eee eee 58 4.2.1 SOAR 2.0... 2 ec tee teen teens 60 4.2.2 ACTAR 2.0... cette tte e et eee 61 4.2.38 Cycand Texai ..... 0. ee eee eens 62 4.2.4 NARS 2.0... 2c ett ttt ents 63 42.0 GLATR and SNePS wo: sasaz sais5 95 22ER5 THEW CES SRPMS SG EME Oe EME Bae 64 4.3 Emergentist Cognitive Architectures ...........0..00 000 cece eee 65 4.3.1 DeSTIN: A Deep Reinforcement Learning Approach to AGI ........... 66 4.3.2 Developmental Robotics Architectures ........0.0000 0.0 ccc eee eee 72 4.4 Hybrid Cognitive Architectures......0... 00000: cece eee teenies 73 4.4.1 Neural versus Symbolic; Global versus Local ............... 002.000 00- 75 4.5 Globalist versus Localist Representations ............0...00 00 eee eee eee 78 4.5.1 CLARION ..... 0.0.0.0 79 4.5.2 The Society of Mind and the Emotion Machine ...................... 80 AB JDUUAD: sms cass SecEE ShFE SESE 48 SHEMG THEW CSTE S SRPMS EME OeE mE SR 80 ABA AD/RCS o.oo ccc c cece eee v cen eeeeeeteteeeerenbrees 81 4.5.5 PolyScheme ........ 00.0.0 e eee eee nee tenes 82 4.5.6 Joshua Blue ........ 0. teens 83 Holst Ji. oss seems amems tees EOS dE SMES MEME SOEMS SUES EME!s dees ee; 84 4.5.8 The Global Workspace ........0...0.000 00 cee 84 4.5.9 The LIDA Cognitive Cycle ....... 0.0... ee eee 85 4.5.10 Psi and MicroPsi .............0 00.020 88 4.5.11 The Emergence of Emotion in the Psi Model....................22255 91 4.5.12 Knowledge Representation, Action Selection and Planning in Psi ....... 93 HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_012910

Sponsored

Page 13 - HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_012911

Contents xv 4.5.13 Psi versus CogPrime ...... 0.0... eee eee 94 5 A Generic Architecture of Human-Like Cognition ........................ 95 5.1 Introduction ........ 00.000 tne teen eee 95 5.2 Key Ingredients of the Integrative Human-Like Cognitive Architecture Diagram 96 5.38 An Architecture Diagram for Human-Like General Intelligence ............... 97 5.4 Interpretation and Application of the Integrative Diagram ................... 104 6 A Brief Overview of CogPrime ................ 0... cc eee 107 6.1 Introduction ........ 00.000 0c eee 107 6.2 High-Level Architecture of CogPrime .......... 0.00.00 eee eee eee eee 107 6.3 Current and Prior Applications of OpenCog ..............0..0 022 eee eee 108 6.3.1 Transitioning from Virtual Agents to a Physical Robot ................ 110 6.4 Memory Types and Associated Cognitive Processes in CogPrime ............. 110 6.4.1 Cognitive Synergy in PLN... eee 111 6.5 Goal-Oriented Dynamics in CogPrime ......... 0.0.0.0 e eee ee eee 113 6.6 Analysis and Synthesis Processes in CogPrime ...............00 2000 c eee eee 114 6.7 Conclusion .......0 0.00 ete etneeeee 116 Section II Toward a General Theory of General Intelligence 7 <A Formal Model of Intelligent Agents .................. 0... cee ee ee 129 Cel, LAPOUCHON, 22s cue ws cme ws (mews (mews Ca Swe WS EMER EMEwS EME WS EME wS KES Hom 129 7.2 A Simple Formal Agents Model (SRAM) .............. 00: eee ee eee eee eens 130 T7210 Goals... ee eee ene e ene ee 131 7.2.2 Memory Stores...... 00... ene ene 132 7.2.3 The Cognitive Schematic ........... 0.000 c cece ee eee 133 7.3 Toward a Formal Characterization of Real-World General Intelligence ......... 135 7.3.1 Biased Universal Intelligence............ 0.00. ee eee 136 7.3.2 Connecting Legg and Hutter’s Model of Intelligent Agents to the Real World... ee cet ete e tne e eens 137 7.3.3 Pragmatic General Intelligence ............ 00... c eee eee 138 7.3.4 Incorporating Computational Cost............0. 0.0000 eee eee 139 7.3.5 Assessing the Intelligence of Real-World Agents ...................-.. 139 7.4 Intellectual Breadth: Quantifying the Generality of an Agent’s Intelligence..... 141 7.5 Conclusion ..... 0... eee eee eee tree eens 142 8 Cognitive Synergy ........... 0... een eens 143 8.1 Cognitive Synergy... 0... eet e nee tenes 143 8.2 Cognitive Synergy .... 0... eee teen een eee 144 8.3 Cognitive Synergy in CogPrime .......... 0.00 cece ee tees 146 8.3.1 Cognitive Processes in CogPrime 1.0.0... 0... cee ee eee 146 8.4 Some Critical Synergies ..... 00... eee eee ees 149 8.5 The Cognitive Schematic ......... 0.00. eee eee eee 151 8.6 Cognitive Synergy for Procedural and Declarative Learning .................. 153 8.6.1 Cognitive Synergy in MOSES... 0... eee 153 8.6.2 Cognitive Synergy in PLN .... 2... eee 155 8.7 Is Cognitive Synergy Tricky?.. 0.0.0... eee ee eee ee 157 HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_012911

Page 14 - HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_012912

xvi Contents 8.7.1 The Puzzle: Why Is It So Hard to Measure Partial Progress Toward Hii lével AGL? ws euses ames €3 8@9mE S@EWS SUES EREMS EOEws dOEAs eos 157 8.7.2 A Possible Answer: Cognitive Synergy is Tricky!...................... 158 8.7.38 Conclusion ......... 000.0 teeta 159 9 General Intelligence in the Everyday Human World ...................... 161 O21 Jntreduction, a:as vacms se3ms Sa M2 Sh EMT SE EMERG SERS CREWE SETHE SG EWE GREE See 161 9.2 Some Broad Properties of the Everyday World That Help Structure Intelligence 162 9.3 Embodied Communication..........0.0..0 00000 eee 163 9.3.1 Generalizing the Embodied Communication Prior .................... 166 GA Naive: PRYSIES ws cuews cuews mews (mews Ca Swe wS Ewe WS MEWS EME ws EME wS KEE Lom 166 9.4.1 Objects, Natural Units and Natural Kinds .......................-.. 167 9.4.2 Events, Processes and Causality ........... 00... c cece ee eee 168 9.4.3 Stuffs, States of Matter, Qualities....... 0... 0. eee eee eee eee 168 9.4.4 Surfaces, Limits, Boundaries, Media .......... 0.0.0.0 cece eee eee eee 168 9.4.5 What Kind of Physics Is Needed to Foster Human-like Intelligence?..... 169 9.5 Folk Psychology ........ 0... 00. eee e nee tenes 170 9.5.1 Motivation, Requiredness, Value ......... 00.00 cece cee eee eee eee 171 9.6 Body and Mind .......... 0... cece eee eet een eee 171 9.6.1 The Human Sensorium........... 2000000 c eect eee eee 171 9.6.2 The Human Body’s Multiple Intelligences ......................00005 172 9.7 The Extended Mind and Body ........... 0.0.0.0 c eee eee 176 9.8 Conclusion ......... 000.0 ett eee teens 176 10 A Mind-World Correspondence Principle ...........................022055 177 10.1 Introduction ..........0 0.00 teens 177 10.2 What Might a General Theory of General Intelligence Look Like? ............ 178 10.3 Steps Toward A (Formal) General Theory of General Intelligence ............. 179 10.4 The Mind-World Correspondence Principle ................00 00022 eee eee 180 10.5 How Might the Mind-World Correspondence Principle Be Useful? ............ 181 10.6 Conclusion ........00..0 0002 ct teeta 182 Section III Cognitive and Ethical Development 11 Stages of Cognitive Development ...............00. 0.00 eee eee 187 11.1 Introduction»... 0.0... ee en eee e eens 187 11.2 Piagetan Stages in the Context of a General Systems Theory of Development .. 188 11.3 Piaget’s Theory of Cognitive Development .............. 0.0... c eee ee eee 188 11.3.1 Perry’s Stages... 0.00. eee teen eee eee 192 11.3.2 Keeping Continuity in Mind .............. 00.0. eee eee eee 192 11.4 Piaget’s Stages in the Context of Uncertain Inference ....................005 193 11.4.1 The Infantile Stage .... 0... eee eee 195 11.4.2 The Concrete Stage.... 00... ee eet eee eee 196 11.4.8 The Formal Stage .......0.. 0.0 eee eee eee 200 114.4 ‘The Réflexivé Sta@¢ s cascs ewe cs es caw eeiws eeews EME ws EME wE EEE Oo 202 HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_012912

Page 15 - HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_012913

Contents xvii 12 The Engineering and Development of Ethics..........................005. 205 121 JPOAWMEtIOH, «205 sa2ms emees Cees ENNeS LE SMES MEME OEMS SERS EME!s dees em; 205 12.2 Review of Current Thinking on the Risks of AGI ................ 00.0002 eee 206 12.3 The Value of an Explicit Goal System. ....... 0.0... eee ee ee 209 12.4 Ethical Synergy ...... 0.00. eee eee tenet eae 210 12.4.1 Stages of Development of Declarative Ethics .................2..000005 211 12.4.2 Stages of Development of Empathic Ethics .....................2.2-- 214 12.4.3 An Integrative Approach to Ethical Development..................... 215 12.4.4 Integrative Ethics and Integrative AGI ...................0 0. eee eee 216 12.5 Clarifying the Ethics of Justice: Extending the Golden Rule in to a Multifactorial Ethical Model ..........0..000 000 cc eee eee 219 12.5.1 The Golden Rule and the Stages of Ethical Development ............. 222 12.5.2 The Need for Context-Sensitivity and Adaptiveness in Deploying Ethical Principles .......0.0.000 0000 ec eee eee 223 12.6 The Ethical Treatment of AGIs ..........0...0 000 c cece ee 226 12.6.1 Possible Consequences of Depriving AGIs of Freedom ................. 228 12.6.2 AGI Ethics as Boundaries Between Humans and AGIs Become Blurred . 229 12.7 Possible Benefits of Closely Linking AGIs to the Global Brain................ 230 12.7.1 The Importance of Fostering Deep, Consensus-Building Interactions Between People with Divergent Views............... 00.0: e ee eee 231 12.8 Possible Benefits of Creating Societies of AGIS ........... 00. cece eee eee 233 12.9 AGI Ethics As Related to Various Future Scenarios ................00 00 eee 234 12.9.1 Capped Intelligence Scenarios ...........00.. 0000 eects 234 12.9.2 Superintelligent AI: Soft-Takeoff Scenarios ................0 0020.00 e eee 235 12.9.3 Superintelligent AI: Hard-Takeoff Scenarios .................2.000005 235 12.9.4 Global Brain Mindplex Scenarios ..............0.0..00 000 eee eee 237 12.10Conclusion: Eight Ways to Bias AGI Toward Friendliness.................... 239 12.10.1 Encourage Measured Co-Advancement of AGI Software and AGI Ethics TDCOLY +s esos WES UES URES UR ERISA CREE CRESS ERERG BAERS BRESS Bret 241 12.10.2Develop Advanced AGI Sooner Not Later .................0..002205- 241 Section IV Networks for Explicit and Implicit Knowledge Representation 13 Local, Global and Glocal Knowledge Representation...................... 245 13.1 Introduction ..........000 0002 eens 245 13.2 Localized Knowledge Representation using Weighted, Labeled Hypergraphs .... 246 13.2.1 Weighted, Labeled Hypergraphs............... 0000: c eee eee eee eee 246 13.3 Atoms: Their Types and Weights ............ 0.00. cee cee eee eee eee 247 13.3.1 Some Basic Atom Types .......... 0.0.00 eee eee 247 13.3.2 Variable Atoms ..........0 000000 cee teen ee 249 13.368 Logical Links o3 casms ease ones os oWams EW EMS EWES ERS BREE BREWS Bm: 251 13.3.4 Temporal Links ..........00 0.00000 tenes 252 13.3.5 Associative Links... 0.2.0.0... 0000 eee ee 253 13.3.6 Procedure Nodes .........00..00 00 cette eee 254 13.3.7 Links for Special External Data Types ..............0 002.00 eee eee eee 254 13.3.8 Truth Values and Attention Values ........... 0.00.00 eee eee eee eee 255 13.4 Knowledge Representation via Attractor Neural Networks ................... 256 HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_012913

Sponsored

Page 16 - HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_012914

xviii Contents 13.4.1 The Hopfield neural net model ..............0..0 022 e eee 256 13.4.2 Knowledge Representation via Cell Assemblies .................2.05- 257 13.5 Neural Foundations of Learning ..........0 0.000 ee eee 258 13.5.1 Hebbian Learning............ 0.0.00 eee ete eee 258 13.5.2 Virtual Synapses and Hebbian Learning Between Assemblies .......... 258 35:38 Netital DArwitiiSitt +2; cases cose: cs s@5m5 $@EME DOES SERS EOE RS Emtes CO: 259 13.6 Glocal Memory .......00 0.0 cc eee t ene e eae 260 13.6.1 A Semi-Formal Model of Glocal Memory .............0...0 00 e eevee 262 13.6.2 Glocal Memory in the Brain ............ 000... eee 263 13.6.3 Glocal Hopfield Networks... .......0.000. 0022 c cee ee 268 13.6.4 Neural-Symbolic Glocality in CogPrime ............. 0000.0 269 14 Representing Implicit Knowledge via Hypergraphs ....................... 271 14.1 Introduction .......00..000 000 tte teen ee 271 14.2: Key Vertex atid Edge Typé$ casas cuine cs ce ees ee ses ems es emo ws Meee MERE OE 271 14.3 Derived Hypergraphs .......... 0.000. c cece tenet eae 272 14.3.1 SMEPH Vertices .........000 0000. tte 272 14.3.2 SMEPH Edges ...... 0... ee eee eens 273 14.4 Implications of Patternist Philosophy for Derived Hypergraphs of Intelligent SYSUCIIS ss cm ems FERS HEME HEME OEE OS CREME CR EMS CR EMS ORES OR EME OR EE Ome 274 14.4.1 SMEPH Principles in CogPrime ............. 000... c eee eee 276 15 Emergent Networks of Intelligence..............00... 002. c eee eee 279 L5el JPOAWEtIOH, «205 seme emees Cees EMNOs LE SMEG MEME SEMS SERS EM E!s dees ema 279 15.2 Small World Networks ........0..000.0 0000 c cette 280 15.3 Dual Network Structure .......0..0.0 000 ete 281 15.3.1 Hierarchical Networks...........0.00.000 00 eee ee 281 15.3.2 Associative, Heterarchical Networks. ........00.000 0000 ccc ees 282 15-38 Dual Networks: « sss: sasa3 ac $5 65 {MEMS EMTWS CM EG SRE EASE wE BREE SR 284 Section V A Path to Human-Level AGI 16 AGI Preschool.......0.... 0... teen eens 289 16.1 Introduction .......... 0.0000 teen teens 289 16.1.1 Contrast to Standard AI Evaluation Methodologies ................... 290 16.2 Elements of Preschool Design ...........00 0.00 e eee eee eee 291 16.3 Elements of Preschool Curriculum ........0... 00000 c eee eee eee 292 16.3.1 Preschool in the Light of Intelligence Theory ....................0-. 293 16.4 Task-Based Assessment in AGI Preschool ............0 0.00 cece ee eee 295 16.5 Beyond Preschool ......... 00... eee ete teens 298 16.6 Issues with Virtual Preschool Engineering .............. 000: cece eee eee 298 16.6.1 Integrating Virtual Worlds with Robot Simulators .................... 301 16.6.2 BlocksNBeads World ............00. 0000 eee cece eee 301 17 A Preschool-Based Roadmap to Advanced AGI.....................000055 307 LG Jnttreduction, asm: isms sa32 Sh 23 SRESE OF TEMG THEW CHES PREM SEEMS OeT mE Sa 307 17.2 Measuring Incremental Progress Toward Human-Level AGI .................. 308 17.3 Conclusion ........00..0 0002 ete eee tees 315 HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_012914

Page 17 - HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_012915

Contents xix 18 Advanced Self-Modification: A Possible Path to Superhuman AGI........ 317 L8el JPOAWEtIOH, «205 ses emtes Cees ENNOE LE SMES MEME SEMS SERS EME!s dees ems 317 18.2 Cognitive Schema Learning .......... 0.000 e cee eee eens 318 18.3 Self-Modification via Supercompilation ..............0..00 000 cee eee 319 18.3.1 Three Aspects of Supercompilation .............0..00 000022 eee eee ee 321 18.3.2 Supercompilation for Goal-Directed Program Modification............. 322 18.4 Self-Modification via Theorem-Proving ........... 0.00 eee eee eee 323 A Glossary ..... 0.00000 tne teen eee 325 A.1 List of Specialized Acronyms.........0.. 00 0c cece eee eee eee 325 A.2 Glossary of Specialized Terms ........... 00000. c cece eee teen eee 326 References 2.0... eet et ete eee t eee 343 HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_012915

Page 18 - HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_012916

HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_012916

Sponsored

Page 19 - HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_012917

Chapter 1 Introduction 1.1 AI Returns to Its Roots Our goal in this book is straightforward, albeit ambitious: to present a conceptual and technical design for a thinking machine, a software program capable of the same qualitative sort of general intelligence as human beings. It’s not certain exactly how far the design outlined here will be able to take us, but it seems plausible that once fully implemented, tuned and tested, it will be able to achieve general intelligence at the human level and in some respects beyond. Our ultimate aim is Artificial General Intelligence construed in the broadest sense, including artificial creativity and artificial genius. We feel it is important to emphasize the extremely broad potential of Artificial General Intelligence systems. The human brain is not built to be modified, except via the slow process of evolution. Engineered AGI systems, built according to designs like the one outlined here, will be much more susceptible to rapid improvement from their initial state. It seems reasonable to us to expect that, relatively shortly after achieving the first roughly human-level AGI system, AGI systems with various sorts of beyond-human-level capabilities will be achieved. Though these long-term goals are core to our motivations, we will spend much of our time here explaining how we think we can make AGI systems do relatively simple things, like the things human children do in preschool. The penultimate chapter of (Part 2 of) the book describes a thought-experiment involving a robot playing with blocks, responding to the request "Build me something I haven’t seen before." We believe that preschool creativity contains the seeds of, and the core structures and dynamics underlying, adult human level genius ... and new, as yet unforeseen forms of artificial innovation. Much of the book focuses on a specific AGI architecture, which we call CogPrime, and which is currently in the midst of implementation using the OpenCog software framework. CogPrime is large and complex and embodies a host of specific decisions regarding the various aspects of intelligence. We don’t view CogPrime as the unique path to advanced AGI, nor as the ultimate end-all of AGI research. We feel confident there are multiple possible paths to advanced AGI, and that in following any of these paths, multiple theoretical and practical lessons will be learned, leading to modifications of the ideas possessed while along the early stages of the path. But our goal here is to articulate one path that we believe makes sense to follow, one overall design that we believe can work. HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_012917

Page 20 - HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_012918

2 1 Introduction 1.2 AGI versus Narrow AI An outsider to the AI field might think this sort of book commonplace in the research literature, but insiders know that’s far from the truth. The field of Artificial Intelligence (AT) was founded in the mid 1950s with the aim of constructing “thinking machines” - that is, computer systems with human-like general intelligence, including humanoid robots that not only look but act and think with intelligence equal to and ultimately greater than human beings. But in the intervening years, the field has drifted far from its ambitious roots, and this book represents part of a movement aimed at restoring the initial goals of the AI field, but in a manner powered by new tools and new ideas far beyond those available half a century ago. After the first generation of AI researchers found the task of creating human-level AGI very difficult given the technology of their time, the AI field shifted focus toward what Ray Kurzweil has called "narrow AI" — the understanding of particular specialized aspects of intelligence; and the creation of AI systems displaying intelligence regarding specific tasks in relatively narrow domains. In recent years, however, the situation has been changing. More and more researchers have recognized the necessity — and feasibility — of returning to the original goals of the field. In the decades since the 1950s, cognitive science and neuroscience have taught us a lot about what a cognitive architecture needs to look like to support roughly human-like general intelli- gence. Computer hardware has advanced to the point where we can build distributed systems containing large amounts of RAM and large numbers of processors, carrying out complex tasks in real time. The AI field has spawned a host of ingenious algorithms and data structures, which have been successfully deployed for a huge variety of purposes. Due to all this progress, increasingly, there has been a call for a transition from the current focus on highly specialized “narrow AI” problem solving systems, back to confronting the more difficult issues of “human level intelligence” and more broadly “artificial general intelligence (AGI).” Recent years have seen a growing number of special sessions, workshops and confer- ences devoted specifically to AGI, including the annual BICA (Biologically Inspired Cognitive Architectures) AAAT Symposium, and the international AGI conference series (one in 2006, and annual since 2008). And, even more exciting, as reviewed in Chapter 4, there are a number of contemporary projects focused directly and explicitly on AGI (sometimes under the name "AGI", sometimes using related terms such as "Human Level Intelligence"). In spite of all this progress, however, we feel that no one has yet clearly articulated a detailed, systematic design for an AGI, with potential to yield general intelligence at the human level and ultimately beyond. In this spirit, our main goal in this lengthy two-part book is to outline a novel design for a thinking machine — an AGI design which we believe has the capability to produce software systems with intelligence at the human adult level and ultimately beyond. Many of the technical details of this design have been previously presented online in a wikibook [Goel0b]; and the basic ideas of the design have been presented briefly in a series of conference papers [GPSL03, GPPG06, Goe09c]. But the overall design has not been presented in a coherent and systematic way before this book. In order to frame this design properly, we also present a considerable number of broader theoretical and conceptual ideas here, some more and some less technical in nature. HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_012918

Page 21 - HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_012919

1.4 The Secret Sauce 3 1.3 CogPrime The AGI design presented here has not previously been granted a name independently of its particular software implementations, but for the purposes of this book it needs one, so we’ve christened it CogPrime . This fits with the name “OpenCogPrime” that has already been used to describe the software implementation of CogPrime within the open-source OpenCog AGI software framework. The OpenCogPrime software, right now, implements only a small fraction of the CogPrime design as described here. However, OpenCog was designed specifically to enable efficient, scalable implementation of the full CogPrime design (as well as to serve as a more general framework for AGI R&D); and work currently proceeds in this direction, though there is a lot of work still to be done and many challenges remain. 1 The CogPrime design is more comprehensive and thorough than anything that has been presented in the literature previously, including the work of others reviewed in Chapter 4. It covers all the key aspects of human intelligence, and explains how they interoperate and how they can be implemented in digital computer software. Part 1 of this work outlines CogPrime at a high level, and makes a number of more general points about artificial general intelligence and the path thereto; then Part 2 digs deeply into the technical particulars of CogPrime. Even Part 2, however, doesn’t explain all the details of CogPrime that have been worked out so far, and it definitely doesn’t explain all the implementation details that have gone into designing and building OpenCogPrime. Creating a thinking machine is a large task, and even the intermediate level of detail takes up a lot of pages. 1.4 The Secret Sauce There is no consensus on why all the related technological and scientific progress mentioned above has not yet yielded AI software systems with human-like general intelligence (or even greater levels of brilliance!). However, we hypothesize that the core reason boils down to the following three points: e Intelligence depends on the emergence of certain high-level structures and dynamics across a system’s whole knowledge base; e We have not discovered any one algorithm or approach capable of yielding the emergence of these structures; e Achieving the emergence of these structures within a system formed by integrating a number of different ATI algorithms and structures requires careful attention to the manner in which | This brings up a terminological note: At several places in this Volume and the next we will refer to the current CogPrime or OpenCog implementation; in all cases this refers to OpenCog as of late 2013. We realize the risk of mentioning the state of our software system at time of writing: for future readers this may give the wrong impression, because if our project goes well, more and more of CogPrime will get implemented and tested as time goes on (e.g. within the OpenCog framework, under active development at time of writing). However, not mentioning the current implementation at all seems an even worse course to us, since we feel readers will be interested to know which of our ideas — at time of writing — have been honed via practice and which have not. Online resources such as http: //opencog.org may be consulted by readers curious about the current state of the main OpenCog implementation; though in future forks of the code may be created, or other systems may be built using some or all of the ideas in this book, ete. HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_012919

Sponsored

Page 22 - HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_012920

4 1 Introduction these algorithms and structures are integrated; and so far the integration has not been done in the correct way. The human brain appears to be an integration of an assemblage of diverse structures and dynamics, built using common components and arranged according to a sensible cognitive archi- tecture. However, its algorithms and structures have been honed by evolution to work closely together — they are very tightly inter-adapted, in the same way that the different organs of the body are adapted to work together. Due to their close interoperation they give rise to the overall systemic behaviors that characterize human-like general intelligence. We believe that the main missing ingredient in AI so far is cognitive synergy: the fitting-together of differ- ent intelligent components into an appropriate cognitive architecture, in such a way that the components richly and dynamically support and assist each other, interrelating very closely in a similar manner to the components of the brain or body and thus giving rise to appropriate emergent structures and dynamics. This leads us to one of the central hypotheses underlying the CogPrime approach to AGI: that the cognitive synergy ensuing from integrating multiple symbolic and subsymbolic learning and memory components in an appro- priate cognitive architecture and environment, can yield robust intelligence at the human level and ultimately beyond. The reason this sort of intimate integration has not yet been explored much is that it’s difficult on multiple levels, requiring the design of an architecture and its component algorithms with a view toward the structures and dynamics that will arise in the system once it is coupled with an appropriate environment. Typically, the AI algorithms and structures corresponding to different cognitive functions have been developed based on divergent theoretical principles, by disparate communities of researchers, and have been tuned for effective performance on different tasks in different environments. Making such diverse components work together in a truly synergetic and cooperative way is a tall order, yet we believe that this — rather than some particular algorithm, structure or architectural principle — is the “secret sauce” needed to create human-level AGI based on technologies available today. 1.5 Extraordinary Proof? There is a saying that “extraordinary claims require extraordinary proof” and by that stan- dard, if one believes that having a design for an advanced AGI is an extraordinary claim, this book must be rated a failure. We don’t offer extraordinary proof that CogPrime, once fully implemented and educated, will be capable of human-level general intelligence and more. It would be nice if we could offer mathematical proof that CogPrime has the potential we think it does, but at the current time mathematics is simply not up to the job. We’ll pursue this direction briefly in Chapter 7 and other chapters, where we'll clarify exactly what kind of mathematical claim “CogPrime has the potential for human-level intelligence” turns out to be. Once this has been clarified, it will be clear that current mathematical knowledge does not yet let us evaluate, or even fully formalize, this kind of claim. Perhaps one day rigorous and detailed analyses of practical AGI designs will be feasible — and we look forward to that day — but it’s not here yet. Also, it would of course be profoundly exciting if we could offer dramatic practical demon- strations of CogPrime’s capabilities. We do have a partial software implementation, in the OpenCogPrime system, but currently the things OpenCogPrime does are too simple to really HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_012920

Page 23 - HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_012921

1.5 Extraordinary Proof? 5 serve as proofs of CogPrime’s power for advanced AGI. We have used some CogPrime ideas in the OpenCog framework to do things like natural language understanding and data mining, and to control virtual dogs in online virtual worlds; and this has been very useful work in multiple senses. It has taught us more about the CogPrime design; it has produced some useful software systems; and it constitutes fractional work building toward a full OpenCog based implemen- tation of CogPrime. However, to date, the things OpenCogPrime has done are all things that could have been done in different ways without the CogPrime architecture (though perhaps not as elegantly nor with as much room for interesting expansion). The bottom line is that building an AGT is a big job. Software companies like Microsoft spend dozens to hundreds of man-years building software products like word processors and operating systems, so it should be no surprise that creating a digital intelligence is also a relatively large- scale software engineering project. As time advances and software tools improve, the number of man-hours required to develop advanced AGI gradually decreases — but right now, as we write these words, it’s still a rather big job. In the OpenCogPrime project we are making a serious attempt to create a CogPrime based AGI using an open-source development methodology, with the open-source Linux operating system as one of our inspirations. But the open-source methodology doesn’t work magic either, and it remains a large project, currently at an early stage. I emphasize this point so that readers lacking software engineering expertise don’t take the currently fairly limited capabilities of OpenCogPrime as somehow a damning indictment of the potential of the CogPrime design. The design is one thing, the implementation another — and the OpenCogPrime implementation currently encompasses perhaps one third to one half of the key ideas in this book. So we don’t have extraordinary proof to offer. What we aim to offer instead are clearly- constructed conceptual and technical arguments as to why we think the CogPrime design has dramatic AGI potential. It is also possible to push back a bit on the common intuition that having a design for human- level AGI is such an “extraordinary claim.” It may be extraordinary relative to contemporary science and culture, but we have a strong feeling that the AGI problem is not difficult in the same ways that most people (including most AI researchers) think it is. We suspect that in hindsight, after human-level AGI has been achieved, people will look back in shock that it took humanity so long to come up with a workable AGI design. As you'll understand once you’ve finished Part 1 of the book, we don’t think general intelligence is nearly as “extraordinary” and mysterious as it’s commonly made out to be. Yes, building a thinking machine is hard — but humanity has done a lot of other hard things before. It may seem difficult to believe that human-level general intelligence could be achieved by something as simple as a collection of algorithms linked together in an appropriate way and used to control an agent. But we suggest that, once the first powerful AGI systems are produced, it will become apparent that engineering human-level minds is not so profoundly different from engineering other complex systems. All in all, we’ll consider the book successful if a significant percentage of open-minded, appropriately-educated readers come away from it scratching their chins and pondering: “Hmm. You know, that just might work.” and a small percentage come away thinking "Now that’s an initiative I'd really like to help with!". HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_012921

Page 24 - HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_012922

6 1 Introduction 1.6 Potential Approaches to AGI In principle, there is a large number of approaches one might take to building an AGI, starting from the knowledge, software and machinery now available. This is not the place to review them in detail, but a brief list seems apropos, including commentary on why these are not the approaches we have chosen for our own research. Our intent here is not to insult or dismiss these other potential approaches, but merely to indicate why, as researchers with limited time and resources, we have made a different choice regarding where to focus our own energies. 1.6.1 Build AGI from Narrow AI Most of the AI programs around today are “narrow AI” programs — they carry out one particular kind of task intelligently. One could try to make an advanced AGI by combining a bunch of enhanced narrow AI programs inside some kind of overall framework. However, we’re rather skeptical of this approach because none of these narrow AI programs have the ability to generalize across domains — and we don’t see how combining them or ex- tending them is going to cause this to magically emerge. 1.6.2 Enhancing Chatbots One could seek to make an advanced AGI by taking a chatbot, and trying to improve its code to make it actually understand what it’s talking about. We have some direct experience with this route, as in 2010 our AI consulting firm was contracted to improve Ray Kurzweil’s online chatbot "Ramona". Our new Ramona understands a lot more than the previous Ramona version or a typical chatbot, due to using Wikipedia and other online resources, but still it’s far from an AGI. A more ambitious attempt in this direction was Jason Hutchens’ a-i.com project, which sought to create a human child level AGI via development and teaching of a statistical learning based chatbot (rather than the typical rule-based kind). The difficulty with this approach, however, is that the architecture of a chatbot is fundamentally different from the architecture of a generally intelligent mind. Much of what’s important about the human mind is not directly observable in conversations, so if you start from conversation and try to work toward an AGI architecture from there, you’re likely to miss many critical aspects. 1.6.3 Emulating the Brain One can approach AGI by trying to figure out how the brain works, using brain imaging and other tools from neuroscience, and then emulating the brain in hardware or software. One rather substantial problem with this approach is that we don’t really understand how the brain works yet, because our software for measuring the brain is still relatively crude. There is no brain scanning method that combines high spatial and temporal accuracy, and none is HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_012922

Sponsored

Page 25 - HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_012923

1.6 Potential Approaches to AGI 7 likely to come about for a decade or two. So to do brain-emulation AGI seriously, one needs to wait a while until brain scanning technology improves. Current AI methods like neural nets that are loosely based on the brain, are really not brain- like enough to make a serious claim at emulating the brain’s approach to general intelligence. We don’t yet have any real understanding of how the brain represents abstract knowledge, for example, or how it does reasoning (though the authors, like many others, have made some speculations in this regard [GMIH08]). Another problem with this approach is that once you’re done, what you get is something with a very humanlike mind, and we already have enough of those! However, this is perhaps not such a serious objection, because a digital-computer-based version of a human mind could be studied much more thoroughly than a biology-based human mind. We could observe its dynamics in real-time in perfect precision, and could then learn things that would allow us to build other sorts of digital minds. 1.6.4 Evolve an AGI Another approach is to try to run an evolutionary process inside the computer, and wait for advanced AGI to evolve. One problem with this is that we don’t know how evolution works all that well. There’s a field of artificial life, but so far its results have been fairly disappointing. It’s not yet clear how much one can vary on the chemical structures that underly real biology, and still get powerful evolution like we see in real biology. If we need good artificial chemistry to get good artificial biology, then do we need good artificial physics to get good artificial chemistry? Another problem with this approach, of course, is that it might take a really long time. Evolution took billions of years on Earth, using a massive amount of computational power. To make the evolutionary approach to AGI effective, one would need some radical innovations to the evolutionary process (such as, perhaps, using probabilistic methods like BOA [Pel05] or MOSES [Loo06] in place of traditional evolution). 1.6.5 Derwe an AGI design mathematically One can try to use the mathematical theory of intelligence to figure out how to make advanced AGI. This interests us greatly, but there’s a huge gap between the rigorous math of intelligence as it exists today and anything of practical value. As we'll discuss in Chapter 7, most of the rigorous math of intelligence right now is about how to make AI on computers with dramati- cally unrealistic amounts of memory or processing power. When one tries to create a theoretical understanding of real-world general intelligence, one arrives at quite different sorts of consider- ations, as we will roughly outline in Chapter 10. Ideally we would like to be able to study the CogPrime design using a rigorous mathematical theory of real-world general intelligence, but at the moment that’s not realistic. The best we can do is to conceptually analyze CogPrime and its various components in terms of relevant mathematical and theoretical ideas; and perform analysis of CogPrime’s individual structures and components at varying levels of rigor. HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_012923

Page 26 - HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_012924

8 1 Introduction 1.6.6 Use heuristic computer science methods The computer science field contains a number of abstract formalisms, algorithms and structures that have relevance beyond specific narrow AI applications, yet aren’t necessarily understood as thoroughly as would be required to integrate them into the rigorous mathematical theory of intelligence. Based on these formalisms, algorithms and structures, a number of "single formal- ism/algorithm focused" AGI approaches have been outlined, some of which will be reviewed in Chapter 4. For example Pei Wang’s NARS ("Non-Axiomatic Reasoning System”) approach is based on a specific logic which he argues to be the "logic of general intelligence" — so, while his system contains many other aspects than this logic, he considers this logic to be the crux of the system and the source of its potential power as an AGI system. The basic intuition on the part of these "single formalism/algorithm focused" researchers seems to be that there is one key formalism or algorithm underlying intelligence, and if you achieve this key aspect in your AGI program, you're going to get something that fundamentally thinks like a person, even if it has some differences due to its different implementation and embodiment. On the other hand, it’s also possible that this idea is philosophically incorrect: that there is no one key formalism, algorithm, structure or idea underlying general intelligence. The CogPrime approach is based on the intuition that to achieve human-level, roughly human- like general intelligence based on feasible computational resources, one needs an appropriate heterogeneous combination of algorithms and structures, each coping with different types of knowledge and different aspects of the problem of achieving goals in complex environments. 1.6.7 Integrative Cognitive Architecture Finally, to create advanced AGI one can try to build some sort of integrative cognitive architec- ture: a software system with multiple components that each carry out some cognitive function, and that connect together in a specific way to try to yield overall intelligence. Cognitive science gives us some guidance about the overall architecture, and computer science and neuroscience give us a lot of ideas about what to put in the different components. But still this approach is very complex and there is a lot of need for creative invention. This is the approach we consider most “serious” at present (at least until neuroscience ad- vances further). And, as will be discussed in depth in these pages, this is the approach we’ve chosen: CogPrime is an integrative AGI architecture. 1.6.8 Can Digital Computers Really Be Intelligent? All the AGI approaches we’ve just mentioned assume that it’s possible to make AGI on digital computers. While we suspect this is correct, we must note that it isn’t proven. It might be that — as Penrose [Pen96], Hameroff [Mam87] and others have argued — we need quantum computers or quantum gravity computers to make AGI. However, there is no evidence of this at this stage. Of course the brain like all matter is described by quantum mechanics, but this doesn’t imply that the brain is a “macroscopic quantum system” in a strong sense (like, say, a Bose-Einstein condensate). And even if the brain does use quantum phenomena in HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_012924

Page 27 - HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_012925

1.7 Five Key Words 9 a dramatic way to carry out some of its cognitive processes (a hypothesis for which there is no current evidence), this doesn’t imply that these quantum phenomena are necessary in order to carry out the given cognitive processes. For example there is evidence that birds use quantum nonlocal phenomena to carry out navigation based on the Earth’s magnetic fields [GRM~ 11]; yet scientists have built instruments that carry out the same functions without using any special quantum effects. The importance of quantum phenomena in biology (except via their obvious role in giving rise to biological phenomena describable via classical physics) remains a subject of debate [AGBD* 08]. Quantum “magic” aside, it is also conceivable that building AGI is fundamentally impossible for some other reason we don’t understand. Without getting religious about it, it is rationally quite possible that some aspects of the universe are beyond the scope of scientific methods. Science is fundamentally about recognizing patterns in finite sets of bits (e.g. finite sets of finite-precision observations), whereas mathematics recognizes many sets much larger than this. Selmer Bringsjord [BZ03], and other advocates of “hypercomputing” approaches to intelligence, argue that the human mind depends on massively large infinite sets and therefore can never be simulated on digital computers nor understood via finite sets of finite-precision measurements such as science deals with. But again, while this sort of possibility is interesting to speculate about, there’s no real reason to believe it at this time. Brain science and AI are both very young sciences and the “working hypothesis” that digital computers can manifest advanced AGI has hardly been explored at all yet, relative to what will be possible in the next decades as computers get more and more powerful and our understanding of neuroscience and cognitive science gets more and more complete. The CogPrime AGI design presented here is based on this working hypothesis. Many of the ideas in the book are actually independent of the “mind can be implemented digitally” working hypothesis, and could apply to AGI systems built on analog, quantum or other non-digital frameworks — but we will not pursue these possibilities here. For the moment, outlining an AGI design for digital computers is hard enough! Regardless of speculations about quantum computing in the brain, it seems clear that AGI on quantum computers is part of our future and will be a powerful thing; but the description of a CogPrime analogue for quantum computers will be left for a later work. 1.7 Five Key Words As noted, the CogPrime approach lies squarely in the integrative cognitive architecture camp. But it is not a haphazard or opportunistic combination of algorithms and data structures. At bottom it is motivated by the patternist philosophy of mind laid out in Ben Goertzel’s book The Hidden Pattern [Goe06al, which was in large part a summary and reformulation of ideas presented in a series of books published earlier by the same author [Goe94], [Goe93a], [Goe93b], [Goe97], [Goe01]. A few of the core ideas of this philosophy are laid out in Chapter 3, though that chapter is by no means a thorough summary. One way to summarize some of the most important yet commonsensical parts of the patternist philosophy of mind, in an AGI context, is to list five words: perception, memory, prediction, action, goals. In a phrase: “A mind uses perception and memory to make predictions about which actions will help it achieve its goals.” HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_012925

Sponsored

Page 28 - HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_012926

10 1 Introduction This ties in with the ideas of many other thinkers, including Jeff Hawkins’ “memory/ predic- tion” theory [B06], and it also speaks directly to the formal characterization of intelligence presented in Chapter 7: general intelligence as “the ability to achieve complex goals in complex environments.” Naturally the goals involved in the above phrase may be explicit or implicit to the intelligent agent, and they may shift over time as the agent develops. Perception is taken to mean pattern recognition: the recognition of (novel or familiar) pat- terns in the environment or in the system itself. Memory is the storage of already-recognized patterns, enabling recollection or regeneration of these patterns as needed. Action is the for- mation of patterns in the body and world. Prediction is the utilization of temporal patterns to guess what perceptions will be seen in the future, and what actions will achieve what effects in the future — in essence, prediction consists of temporal pattern recognition, plus the (implicit or explicit) assumption that the universe possesses a "habitual tendency" according to which previously observed patterns continue to apply. 1.7.1 Memory and Cognition in CogPrime Each of these five concepts has a lot of depth to it, and we won’t say too much about them in this brief introductory overview; but we will take a little time to say something about memory in particular. As we'll see in Chapter 7, one of the things that the mathematical theory of general intelli- gence makes clear is that, if you assume your AI system has a huge amount of computational resources, then creating general intelligence is not a big trick. Given enough computing power, a very brief and simple program can achieve any computable goal in any computable environ- ment, quite effectively. Marcus Hutter’s AT XI" design [Hut05] gives one way of doing this, backed up by rigorous mathematics. Put informally, what this means is: the problem of AGI is really a problem of coping with inadequate compute resources, just as the problem of natural intelligence is really a problem of coping with inadequate energetic resources. One of the key ideas underlying CogPrime is a principle called cognitive synergy, which explains how real-world minds achieve general intelligence using limited resources, by appropri- ately organizing and utilizing their memories. This principle says that there are many different kinds of memory in the mind: sensory, episodic, procedural, declarative, attentional, intentional. Each of them has certain learning processes associated with it; for example, reasoning is associated with declarative memory. Synergy arises here in the way the learning processes associated with each kind of memory have got to help each other out when they get stuck, rather than working at cross-purposes. Cognitive synergy is a fundamental principle of general intelligence — it doesn’t tend to play a central role when you’re building narrow-AI systems. In the CogPrime approach all the different kinds of memory are linked together in a single meta-representation, a sort of combined semantic/neural network called the AtomSpace. It represents everything from perceptions and actions to abstract relationships and concepts and even a system’s model of itself and others. When specialized representations are used for other types of knowledge (e.g. program trees for procedural knowledge, spatiotemporal hierarchies for perceptual knowledge) then the knowledge stored outside the AtomSpace is represented via HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_012926

Page 29 - HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_012927

1.8 Virtually and Robotically Embodied AI 11 tokens (Atoms) in the AtomSpace, allowing it to be located by various cognitive processes, and associated with other memory items of any type. So for instance an OpenCog AI system has an AtomSpace, plus some specialized knowledge stores linked into the AtomSpace; and it also has specific algorithms acting on the AtomSpace and appropriate specialized stores corresponding to each type of memory. Each of these algo- rithms is complex and has its own story; for instance (an incomplete list, for more detail see the following section of this Introduction): e Declarative knowledge is handled using Probabilistic Logic Networks, described in Chapter 34 and others; e Procedural knowledge is handled using MOSES, a probabilistic evolutionary learning algo- rithm described in Chapter 21 and others; e Attentional knowledge is handled by ECAN (economic attention allocation), described in Chapter 23 and others; e OpenCog contains a language comprehension system called RelEx that takes English sen- tences and turns them into nodes and links in the AtomSpace. It’s currently being ex- tended to handle Chinese. RelEx handles mostly declarative knowledge but also involves some procedural knowledge for linguistic phenomena like reference resolution and semantic disambiguation. But the crux of the CogPrime cognitive architecture is not any particular cognitive process, but rather the way they all work together using cognitive synergy. 1.8 Virtually and Robotically Embodied AI Another issue that will arise frequently in these pages is embodiment. There’s a lot of debate in the AI community over whether embodiment is necessary for advanced AGI or not. Personally, we doubt it’s necessary but we think it’s extremely convenient, and are thus considerably interested in both virtual world and robotic embodiment. The CogPrime architecture itself is neutral on the issue of embodiment, and it could be used to build a mathematical theorem prover or an intelligent chat bot just as easily as an embodied AGI system. However, most of our attention has gone into figuring out how to use CogPrime to control embodied agents in virtual worlds, or else (to a lesser extent) physical robots. For instance, during 2011-2012 we are involved in a Hong Kong government funded project using OpenCog to control video game agents in a simple game world modeled on the game Minecraft [GPC™ 11]. Current virtual world technology has significant limitations that make them far less than ideal from an AGI perspective, and in Chapter 16 we will discuss how they can be remedied. However, for the medium-term future virtual worlds are not going to match the natural world in terms of richness and complexity — and so there’s also something to be said for physical robots that interact with all the messiness of the real world. With this in mind, in the Artificial Brain Lab at Xiamen University in 2009-2010, we con- ducted some experiments using OpenCog to control the Nao humanoid robot [GD09]. The goal of that work was to take the same code that controls the virtual dog and use it to control the physical robot. But it’s harder because in this context we need to do real vision processing and real motor control. A similar project is being undertaken in Hong Kong at time of writ- ing, involving a collaboration between OpenCog AI developers and David Hanson’s robotics HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_012927

Page 30 - HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_012928

12 1 Introduction group. One of the key ideas involved in this project is explicit integration of subsymbolic and more symbolic subsystems. For instance, one can use a purely subsymbolic, hierarchical pattern recognition network for vision processing, and then link its internal structures into the nodes and links in the AtomSpace that represent concepts. So the subsymbolic and symbolic systems can work harmoniously and productively together, a notion we will review in more detail in Chapter 26. 1.9 Language Learning One of the subtler aspects of our current approach to teaching CogPrime is language learning. Three relatively crisp and simple approaches to language learning would be: e Build a language processing system using hand-coded grammatical rules, based on linguistic theory; e Train a language processing system using supervised, unsupervised or semisupervised learn- ing, based on computational linguistics; e Have an AI system learn language via experience, based on imitation and reinforcement and experimentation, without any built-in distinction between linguistic behaviors and other behaviors. While the third approach is conceptually appealing, our current approach in CogPrime (de- scribed in a series of chapters in Part 2) is none of the above, but rather a combination of the above. OpenCog contains a natural language processing system built using a combination of the rule-based and statistical approaches, which has reasonably adequate functionality; and our plan is to use it as an initial condition for ongoing adaptive improvement based on embodied communicative experience. 1.10 AGI Ethics When discussing AGI work with the general public, ethical concerns often arise. Science fic- tion films like the Terminator series have raised public awareness of the possible dangers of advanced AGI systems without correspondingly advanced ethics. Non-profit organizations like the Singularity Institute for AI ( (http://singinst.org) have arisen specifically to raise attention about, and foster research on, these potential dangers. Our main focus here is on how to create AGI, not how to teach an AGI human ethical principles. However, we will address the latter issue explicitly in Chapter 12, and we do think it’s important to emphasize that AGI ethics has been at the center of the design process throughout the conception and development of CogPrime and OpenCog. Broadly speaking there are (at least) two major threats related to advanced AGI. One is that people might use AGIs for bad ends; and the other is that, even if an AGI is made with the best intentions, it might reprogram itself in a way that causes it to do something terrible. If it’s smarter than us, we might be watching it carefully while it does this, and have no idea what’s going on. HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_012928

Sponsored

Page 31 - HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_012929

1.12 Key Claims of the Book 13 The best way to deal with this second “bad AGI” problem is to build ethics into your AGI architecture — and we have done this with CogPrime, via creating a goal structure that explicitly supports ethics-directed behavior, and via creating an overall architecture that supports “ethical synergy” along with cognitive synergy. In short, the notion of ethical synergy is that there are different kinds of ethical thinking associated with the different kinds of memory and you want to be sure your AGI has all of them, and that it uses them together effectively. In order to create AGI that is not only intelligent but beneficial to other sentient beings, ethics has got to be part of the design and the roadmap. As we teach our AGI systems, we need to lead them through a series of instructional and evaluative tasks that move from a primitive level to the mature human level — in intelligence, but also in ethical judgment. 1.11 Structure of the Book The book is divided into two parts. The technical particulars of CogPrime are discussed in Part 2; what we deal with in Part 1 are important preliminary and related matters such as: e The nature of real-world general intelligence, both conceptually and from the perspective of formal modeling (Section I). e The nature of cognitive and ethical development for humans and AGIs (Section IIT). e The high-level properties of CogPrime, including the overall architecture and the various sorts of memory involved (Section IV). e What kind of path may viably lead us from here to AGI, with focus laid on preschooL-type environments that easily foster humanlike cognitive development. Various advanced aspects of AGI systems, such as the network and algebraic structures that may emerge from them, the ways in which they may selfmodify, and the degree to which their initial design may constrain or guide their future state even after long periods of radical self-improvement (Section V). One point made repeatedly throughout Part 1, which is worth emphasizing here, is the current lack of a really rigorous and thorough general technical theory of general intelligence. Such a theory, if complete, would be incredibly helpful for understanding complex AGI architectures like CogPrime. Lacking such a theory, we must work on CogPrime and other such systems using a combination of theory, experiment and intuition. This is not a bad thing, but it will be very helpful if the theory and practice of AGI are able to grow collaboratively together. 1.12 Key Claims of the Book We will wrap up this Introduction with a systematic list of some of the key claims to be argued for in these pages. Not all the terms and ideas in these claims have been mentioned in the preceding portions of this Introduction, but we hope they will be reasonably clear to the reader anyway, at least in a general sense. This list of claims will be revisited in Chapter 49 near the end of Part 2, where we will look back at the ideas and arguments that have been put forth in favor of them, in the intervening chapters. HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_012929

Page 32 - HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_012930