EFTA00024175 - EFTA00024219

Document EFTA00024175 includes a manuscript of a research update, "Facilitators and Barriers to Child Sexual Abuse (CSA) Disclosures: A Research Update (2000-2016)" by Ramona Alaggia, Delphine Collin-Vezina, and Rusan Lateef.

The document contains a manuscript focusing on factors that either promote or inhibit the disclosure of child sexual abuse (CSA). The research aims to identify ways to encourage earlier disclosures, provide timely support to survivors, and prevent further victimization. The study analyzes 33 studies from 2000-2016 and identifies key themes related to disclosure, including the iterative nature of disclosure, the influence of social-ecological factors, the impact of age and gender, the lack of a life-course perspective in research, and the fact that barriers to disclosure still outweigh facilitators.

Key Highlights

- •The document is a manuscript of research on child sexual abuse (CSA) disclosures.

- •Key people involved in the research include Ramona Alaggia, Delphine Collin-Vezina, and Rusan Lateef.

- •The research identifies that barriers to CSA disclosure continue to outweigh facilitators.

Frequently Asked Questions

Books for Further Reading

Perversion of Justice: The Jeffrey Epstein Story

Julie K. Brown

Investigative journalism that broke the Epstein case open

Filthy Rich: The Jeffrey Epstein Story

James Patterson

Bestselling account of Epstein's crimes and network

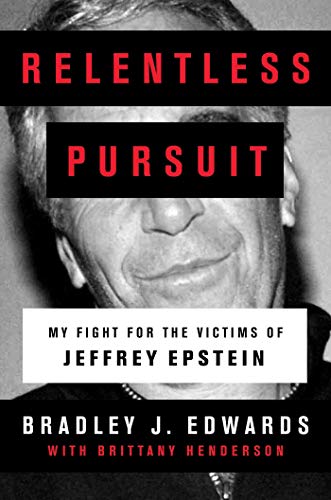

Relentless Pursuit: My Fight for the Victims of Jeffrey Epstein

Bradley J. Edwards

Victims' attorney's firsthand account

Document Information

Bates Range

EFTA00024175 - EFTA00024219

Pages

45

Document Content

Page 1 - EFTA00024175

Exhibit B EFTA00024175

Page 2 - EFTA00024176

Ctc•ckl.e 4.pdzAco Review Manuscript Facilitators and Barriers to Child Sexual Abuse (CSA) Disclosures: A Research Update (2000-20 I 6) Ramona Alaggial , Delphine Collin-Vezina2, and Rusan Lateefl TRAUMA. VIOLENCE & ABUSE 2019, Vol. 20(2) 260-283 C The Author(s) 2017 Artock roust guidelines: sacepub comlioumalvptimoskin DOI, 10117711124838017697312 nals sagepuboornlhomakva OSAGE Abstract Identifying and understanding factors that promote or inhibit child sexual abuse (CSA) disclosures has the potential to facilitate earlier disclosures, assist survivors to receive services without delay, and prevent further sexual victimization. Timely access to therapeutic services can mitigate risk to the mental health of survivors of all ages. This review of the research focuses on CSA disdosures with children, youth, and adults across the life course. Using Kiteley and Stogdon's literature review framework. 33 studies since 2000 were identified and analyzed to extrapolate the most convincing findings to be considered for practice and future research. The centering question asked: What is the state of CSA disclosure research and what can be learned to apply to practice and future research? Using Braun and Clarke's guidelines for thematic analysis. five themes emerged: (I) Disclosure is an iterative, interactive process rather than a discrete event best done within a relational context; (2) contemporary disclosure models reflect a social—ecological, person-in-environment orientation for understanding the complex interplay of individual, familial, contextual, and cultural factors involved in CA disclosure; (3) age and gender significantly influence disclosure; (4) there is a lack of a life-course perspective; and (5) barriers to disclosure continue to outweigh facilitators. Although solid strides have been made in understanding CSA disclosures, the current state of knowledge does not fully capture a cohesive picture of dis. dosure processes and pathways over the life course. More research is needed on environmental. contextual, and cultural factors. Barriers continue to be identified more frequently than facilitators, although dialogical forums are emerging as important facil- itators of CSA disclosure. Implications for practice in facilitating CSA disclosures are discussed with recommendations for future research. Keywords sexual abuse, child abuse, cultural contexts Introduction Timely access to supportive and therapeutic resources for child sexual abuse (CSA) survivors can mitigate risk to the health and mental health well-being of children, youth, and adults. Identifying and understanding factors that promote or inhibit CSA disclosures have the potential to facilitate earlier disclo- sures, assist survivors to receive services without delay, and potentially prevent further sexual victimization. Increased knowledge on both the factors and the processes involved in CSA disclosures is timely when research continues to show high rates of delayed disclosures (Collin-VEzina, Sablonni, Palmer, & Milne, 2015; Crisma, Bascelli, Paci, & Romito, 2004; Easton, 2013; Goodman-Brown, Edelstein, Goodman, Jones, & Gordon, 2003; Hershkowitz, Lanes, & Lamb; 2007; Jonzon & Lindblad, 2004; McElvaney, 2015; Smith et al., 2000). Incidence studies in the United States and Canada report decreasing CSA rates (Fallon et al., 2015; Finkelhor, Shattuck, Turner, & Hamby, 2014; Trocme et al., 2005, 2008), while at the same time global trends from systematic reviews and meta- analyses have found concerning rates of CSA, with averages of 18-20% for females and of 8-10% for males (Pereda, Guilera, Fours, & Gomez-Benito, 2009). The highest rates found for girls is in Australia (21.5%) and for boys in Africa (19.3%), with the lowest rates for both girls (11.3%) and boys (4.1%) reported in Asia (Stoltenborgh, van Uzendoorn, Euser, & Bakermans-Kranenburg, 20 I 1). These findings point to the incongruence between the low number of official reports of I Factor-Inwentash Faculty of Social Work. University of Toronto. Toronto. Ontario. Canada 2 Centre for Research on Children and Families. School of Social Work, McGill University. Montreal. Qubec. Canada Corresponding Author: Ramona Alaggia. Factor-Inwentash Chair in Children's Mental Health. Factor- Inwentash Faculty of Social Work. University of Toronto. 246 Moor St West. Toronto, Ontatio, Canada M4K I W I. ramonaalaggiaeutorortoca EFTA00024176

Page 3 - EFTA00024177

Alaggia et at 261 CSA to authorities and the high rates reported in prevalence studies. For example, a meta-analysis conducted by Stolten- borgh, van LIzendoom, Euser, and Bakermans-Kranenburg (2011) combining estimations of CSA in 217 studies published between 1980 and 2008 revealed rates of CSA to be more than 30 times greater in studies relying on self-reports (127 in 1,000) than in official report inquiries, such as those based on data from child protection services and the police (4 in 1,000) (Ju- lian, Cotter, & Perreault, 2014; Statistics Canada 2013). In other words, while 1 out of 8 people retrospectively report having experienced CSA, official incidence estimates indicate only 1 per 250 children. In a survey of Swiss child services, Maier, Mohler-Kuo, Landholt, Schnyder, and Jud (2013) fur- ther found 2.68 cases per 1,000 of CSA disclosures, while in a recent comprehensive review McElvaney (2015) details the high prevalence of delayed, partial, and nondisclosures in childhood indicating a persistent trend toward withholding CSA disclosure. It is our view that incidence statistics are likely an under- estimation of CSA disclosures, and this drives the rationale for the current review. Given the persistence of delayed disclosures with research showing a large number of survivors only dis- closing in adulthood (Collin-Vezina et al., 2015; Easton, 2013; Hunter, 2011; McElvaney, 2015; Smith et al., 2000), these issues should be a concern for practitioners, policy makers, and the general public (McElvaney, 2015). The longer disclosures are delayed, the longer individuals potentially live with serious negative effects and mental health problems such as depres- sion, anxiety, trauma disorders, and addictions, without receiv- ing necessary treatment. This also increases the likelihood of more victims falling prey to undetected offenders. Learning more about CSA disclosure factors and processes to help advance our knowledge base may help professionals to facil- itate earlier disclosures. Previous literature reviews examining factors influencing CSA disclosure have served the field well but are no longer current. Important contributions on CSA disclosures include Paine and Hansen's (2002) original review covering the liter- ature largely from the premillennium era, followed by London, Bruck, Ceci, and Shuman's (2005) subsequent review, which may not have captured publications affected by "lag to print" delays so common in peer-reviewed journals. These reviews are now dated and therefore do not take into account the plethora of research that has been accumulated over the past 15 years. Other recent reviews exist but with distinct contribu- tions on the dialogical relational processes of disclosure (Reit- sema & Grietens, 2015), CSA disclosures in adulthood (Tener & Murphy, 2015), and delayed disclosures in childhood (McEl- vaney, 20I5). This literature review differs by focusing on CSA disclosures in children, youth, and adults from childhood and into adulthood—over the life course. Method Kiteley and Stogdon's (2014) systematic review framework was utilized to establish what has been investigated in CSA disclosure research, through various mixed methods, to high- light the most convincing findings that should be considered for future research, practice, and program planning. This review centered on the question: What is the state of CSA disclosure research and what can be learned to apply to future research and practice? By way of clarification, the term systematic refers to a methodologically sound strategy for searching liter- ature on studies for knowledge construction, in this case the CSA disclosure literature, rather than intervention studies. The years spanned for searching the literature were 2000-2016, building on previous reviews without a great deal of overlap. Retrieval of relevant research was done by searching interna- tional electronic databases: PsycINFO, PsycARTICLES, Edu- cational Resources Information Center, Canadian Research Index, International Bibliography of the Social Sciences, Pub- lished International Literature on Traumatic Stress, Sociologi- cal Abstracts, Social Service Abstracts, and Applied Social Science Index and Abstracts. This review searched peer- reviewed studies. A search of the gray literature (unpublished literature such as internal agency documents, government reports, etc.) was beyond the scope of this review because unpublished studies are not subjected to a peer-review process. Keyword search terms used were child sexual abuse, childhood sexual abuse, disclosure, and telling. A search of the 9 databases produced 322 peer-reviewed articles. Selected search terms yielded 200 English publica- tions, I French study, and 1 Portuguese review. The search was further refined by excluding studies focusing on forensic inves- tigations, as these studies constitute a specialized legal focus on interview approaches and techniques. As well, papers that focused exclusively on rates and responses to CSA disclosure were excluded, as these are substantial areas unto themselves, exceeding the aims of the review question. Review articles were also excluded. Once the exclusion criteria were applied, the search results yielded 33 articles. These studies were sub- jected to a thematic analysis as described by Braun and Clarke (2006). This entailed (I) multiple readings by the three authors; (2) identifying patterns across studies by coding and charting specific features; (3) examining disclosure definitions used, sample characteristics, and measures utilized; and (4) major findings were extrapolated. Reading of the articles was initially conducted by the authors to identify general trends in a first level of analyses and then subsequently to identify themes through a deeper second-level analyses. A table of studies was generated and was continuously revised as the selection of studies was refined (see Table 1). Key Findings First-level analysis of the studies identified key study charac- teristics. Trends emerged around definitions of CSA disclosure, study designs, and sampling issues. First, in regard to defini- tions, the term "telling" is most frequently used in place of the term disclosure. In the absence of standardized questionnaires or disclosure instruments, telling emerges as a practical term more readily understood by study participants. Several EFTA00024177

Sponsored

Page 4 - EFTA00024178

rig Table I. Ch d Sexua Abuse (CSA) D sc osure Stud es: 2000-2016. Study Purpose Des gn Samp e F nd ngs Summary Gagner and Co n- Vez na (2016) Braze ton (2015) Co n-Vez na, Sab onn . Pa mer, and M ne (20 I 5) Lec erc and Wort ey (20 I 5) To exp ore d sc osure processes for ma e v ct ms of CA To exp ore the mean rig Afr can Amer can women make of the r traumat c exper ences w th CSA and how they d sc osed across the fe course To prov de a mapp ng of factors that prevent CSA d sc osures through an eco og ca ens from a samp e of CSA adu t sury von. Study object yes nvest gated the factors that fac tate CSA d sc osures Phenomeno og ca methodo ogy used to ntery ew ma e CSA sury vors. The Long Intery ew Method (LIM) gu ded data co ea on and ana yses. Co ect ve case study des gn w th us ng narrat ve wad t on (storyboard) for data co ea on and am ys s. Qua tat ve ntery ew ng Qua at ve des gn us ng LIM. Adu t ma e ch d sexua offenders were ntery ewed to exam ne pred ctors of 17 men ranged n age from 19 to 67— average age 47. Purpos ve samp rig strategy was used 17 Afr can Amer can women n m d- fe between 40 and 63 who exper enced ntrafam a CSA_ Purpos ye. snowba ng strategy 67 ma e and fema e CSA adu t sury vors (76% dent f ed as fema e and 24% as ma e). Age ranges from 19 to 69 years (M = 44.9). Purpos ve samp ng strategy 369 adu t ma es who had been cony cted of a sexua offense aga nst a ch d aged between I The major ty of the men n the study wa ted unt adu thood to d sc ose the r abuse. w th negat ve stereotypes contr but ng to the r de ayed d sc osures. Negat ve stereotypes contr buted to de ayed d sc osure w th try ng to forget. Break ng so at on was c ted as a mot vator to d sc osure a ong w th the a d of var ous forms of med a on d sc osure. Important contextua ssues such as negat ve stereotyp ng of ma es. sexua ty. and v ct ms were noted. Soc a med a was seen as a fac tator of d sc osures CSA onset was arge y between the ages 5 and 9. No one ever ta ked to them about sex, so they d dn't have anguage to d sc ose. Barr en: fear of fam y breakdown and remova , not want ng to tarn sh the fam y's name, and fear of retr but on by tam y members f they d sc osed. Pattern of st fed and d sm ssed d sc osures dent f ed over the fe course. A 17 part c pants dent f ed sp r tua ty as a pr mary source of strength throughout the fe course Three broad categor es were dent fed as barr en to CSA d sc osure: Barr ers from w th n- nterna zed v a m b am ng, mechan sms to protect onese f. and mmature deve opment at t me of abuse: barr en n re at on to others—v o ence and dysfuna on n the fam y, power dynam a. awareness of the mpact of to ng, and frag e soc a network; barr en n re at on to the soc a wor d abe ng, taboo of sexua ty, ack of sery ces ava ab e. and cu ture or t me per od. D sc osure ncreased w th the age of the v ct m: f penetrat on had occurred, f the v ct m was re aced to the offender, f the v ct m was not v ng w th die offender at A part c pants had d sc osed and rece ved sery ces before part c pat ng n the study. Member check ng cou d not be done w th the part c pants to check themes. Sma but surf c ent s ze for a qua tat ve nqu ry. Otherw se, h gh eve of r gor n estab sh ng trustworth ness of the data and ana ys s. Retrospect ve study cou d mp y reca ssues One of few stud es to focus exc us ye y on Afr can Amer can women. Sma but stiff cent s ze for a qua tat ve nqu ry. Important cu tura and contextua ssues were brought forward. Retrospect ye study that may have been affected by reca ssues. Use of a fe-course perspect ye as a theoret ca ens for understand ng CSA n the m dd e to ater years of fe that shou d be cons dered n further nvest gat ons Ha f of the part c pants had not d sc osed the r CSA exper ences before the age of 19. Retrospect ye aspect of the study cou d mp y reca ssues. A pan c pants had d sc osed and rece ved counse ng at some before part c pat ng n the study. H gh eve of rgor n estab sh ng trustworth ness of the data and ana ys s Offender generated data through se (-reports cou d be subject to cogn t ve d stort ons— m n m sat on or exaggerat ons. (continued) EFTA00024178

Page 5 - EFTA00024179

Table I. (cont nued) Study Purpose Des gn Samp e F nd rags Summary McE vaney and Cu hane (2015) Dumont, Messerschm tt V a, Bohu. and Rey-Sa mon (2014) Easton. Sa tzman. and W 5 (2014) To nvest gate the teas b ty of us ng ch d assessments as data sources of nforma CSA d sc osure. To assess f these reports prov de substant ye data on d sc osures Th s study a med to exp ore how the re at onsh p between the perpetrator and the v ct m, espec a y whether these re at ons are ntrafam a or extrafam a, mpact CSA d sc osure Study focus was on dent f cat on of barr en to CSA d sc osure w th ma e sury von v ct m d sc osure. Sem structured ntery ews based on the QID quest onna re. F e reports of ch dren seen for assessment n a ch d sexua abuse un t n a ch dren's hosp ta were rev ewed F e reports of ch dren seen for assessment n a ch d sexua abuse un t n a ch dren's hasp ta were rev ewed Us ng qua tat ve content ana ys s, researchers conducted a secondary ana ys s of on ne survey data. the 2010 Heath and We -Be ng Survey. that nc uded men w th se (-reported CSA h stor es w th an open-ended tem on d sc osure barr ers and I7 years o d. Major ty were Wh te. uneducated, a most ha f unemp oyed before the r arrest Content ana ys s was comp eted on 39 f es (32 fema es and 7 ma es) based on a cod ng framework. Parents were asked to consent to have the r ch d's f e rev ewed for the study. V a ms assessed were 12-18 years of age 220 m nor v a rns- 78.2% fema e v a ms. 41.8% aged between 14 and 18 (most preva ent age range). and 48.2% were abused by a fam y member 460 men w th CSA h stor es comp eted an anonymous, Internet- based survey. Recta ted from sury yore organ zat ons. Age range of 18-84 years. Two th rds of respondents reported c ergy-re ated abuse. Major ty of respondents were Wh te the t me of the abuse, or f the v a m res sted dur ng the offense. Ma e v a ms and v a ms from dysfuna ona backgrounds were ess ke y to d sc ose Major ty of ch dren to d the r mothers (43%) and peers (33%) f rst_ Three major themes were dent fed as nf uenc ng the d sc osure process: (I) fee ng d stressed. (2) opportun ty to te . and (3) fears for se f. Add t ona themes of be ng be eyed. shame/se f-b ame. and peer nf uence were a so dent fed D sc osure processes were more cone ex when t concerned sexua abuse comm tted by ntrafam a perpetrator 60% of the v a ms revea the facts seven years after, and most often to nd v dua s outs de the fam y (78.6% of the d sc osures done at schoo): on the contrary. extrafam a d sc osures take p ace more spontaneous y and qu ck y: 80% of the v a ms revea the facts a few days after, most often to the r mother or peers Vast major ty of part c pants (94.6%) were sexua y abused by another ma e. Durst on of sexua abuse broke down nto: 30.2% ess than 6 months. 32.3% 6 months to 3 years. and 34.3% more than 3 years. Ten years o d was average age of CSA onset Ten categor es of barr en were c ass fed nto three doma ns: (I) soc opo t ca: mascu n ty. m ted resources; (2) nterpersona : m strust of others, fear of be ng abe ed "gay," safety and protect on ssues, past responses: and (3) persona: ntema emot ons. see ng the exper ence as sexua abuse. and sexua or enat on. Penpect ves of offenders on vu nerab ty of v ct ms n re at on to d sc osure cou d be mportant nformat on to nform ntervent ons The samp e s ze s sma but w toner bute to a arge mu t s te study n Ire and. Serves as an mportant exp oratory p of br ng ng forward d sc osure themes for cons dent on The re at onsh p w th the perpetrator has a s gn f cant mpact on both t m ng and rec p ent of d sc osure. w th ntrafam a abuses ess ke y to be d sc osed prompt y and w th n the tam y system At t me of the study. th s was the argest qua tat ve data set to have been ana yzed w th an exp c t focus on adu t ma e sury vors' percept ons of barr en to CSA d sc osure. Because the samp e was m ted n terms of the ow percentage of rac a m nor t es (9.3%). d sc osure d fferences based on race or ethn c ty were not d scerned. The major ty of abuse reported was by c ergy wh ch m ght present a un que set of barr ers to d sc osure (continued) EFTA00024179

Page 6 - EFTA00024180

Pt' Table I. (cont nued) Study Purpose Des gn Samp e F nd ngs Summary Easton (2013) McE vaney. Greene. and Hogan (2012) Schonbucher, Ma er, Moh er-Kuo, Schnyder, and Lando t (20 I 2) Study purpose was to descr be ma e CSA d sc osure processes us ng a fe span approach exam n ng d fferences based on age. A so. to exp ore re at onsh ps between d sc osure attr butes and men's menta hea th Qua tat ve study asked the centre research quest on: "How do ch dren te ?" Object ve was to deve op theory of how ch dren te of the r CSA d sc osure exper ences. Parents were ntery ewed. To nvest gate the process of CSA d sc osure w th ado escents from the genera popu at on who had exper enced CSA. How many d sc osed, who d d Cross-sect ona survey des grt.E gbe part c pants were screened and comp eted an anonymous, Internet- based survey dur ng 2010. Measures used: Genera Menta Heath D stress Sca e and Genera Assessment of Ind v dua Needs. Quest ons re ated to CSA d sc osure and supports were nc uded Grounded theory method study. Intery ews were conducted. L ne-by- ne open and ax a cod ng was conducted on verbat m transcr pts Data co ect on was through face-to-face qua tat ve ntery ews. Standard zed quest ons and measures were adm n stered on fam y s tuat on. soc odemograph c Purpos ve samp ng of 487 men from three nat ona organ zat ons devoted to ra s ng awareness of CSA among men. Age range: 19-84 years. Mean age for onset of CSA was 10.3 years Samp e of 22 young peop 16 g r s and 6 boys: age range: 8-18 years: 22 ntery ewed n ton between the ages of 8 and 18. M xed samp e of some endur ng ntrafam a CSA, some extrafam a CSA, and two endured both forms Conven ence samp e of 26 sexua y v ct m zed ado escents. 23 g r s and 3 boys. Age range: I5—I8 years. On ne advert cements and f yen were used to recru t youth from O der age and be ng abused by a fam y member were both re ated to de ays n d sc osure. Most part c pants who to d someone dur ng ch dhood d d not rece ve emot ona y support ve or protect ve responses and the he pfu ness of responses across the fe span was m xed. De ays n te ng were s gn f cant per ods oft me (over 20 years). Approx mate y one ha f of the part c pants f rst to d about the sexua abuse to a spouse/partner (27%) or a menta hea th profess ona (20%): 42% of part c pants reported that the r most he pfu d scuss on was w th a menta hea th profess ona. However. unhe pfu responses caused most menta d stress. C n ca recommendat ons nc uded more of a fe-course perspect ve be adopted. understand ng mpact of unhe pfu responses and the mportance of expand ng networks for ma e sury von A theoret ca mode was deve oped that conceptua zes the process of CSA d sc osure as one of conta n ng the secret (I) the act ve w thho d ng of the secret on the part of the ch d; (2) the exper ence of a "pressure cooker effect" ref ect ng a conf ct between the w sh to te and the w sh to keep the secret; and (3) the conf d ng tse f wh ch often occurs n the context of a trusted re at onsh p. These were der ved from e even categor es that were deve oped through open and ax a cod ng Less than one th rd of part c pants mmed ate y d sc osed CSA to another person. In most cases, rec p ents of both mmed ate and de ayed d sc osure were to peers. More than one th rd of part c pants had never d sc osed the abuse to a parent. Part c pants reported re uctance to d sc ose to parents so as Purpos ye samp ng of men from awareness ra s ng organ zat ons may have attracted part cu ar part c pants who had a ready d sc osed and rece ved he p. Part c pants needed to have access to Internet wh ch wou d have e m nated men n ower SES groups and requ red prof c ency n Eng sh wh ch wou d e m nate certa n cu tura groups. However. the samp ng strategy ga ned access to a predom nant y h dden popu at on. Important c n ca recommendat ons are made w th an emphas son a fe-course focus Modest but suff c ent samp e for an exp oratory qua tat ve nqu ry. H gh eve of trustworth ness r gor. A subsamp e of random y se ected transcr pts was ndependent y coded. Very young ch dren and young adu is were not captured n th s samp e. Transferab ty of f nd ngs can on y be made to the age range samp ed n the context of Ire and Two th rds of the samp e d d not d sc ose r ght away. Strengthen ng parent—ch d re at onsh ps may be one of the most mportant ways to ncrease d sc osure to parents. D sc osure to peers has been found a common trend n other (continued) EFTA00024180

Sponsored

Page 7 - EFTA00024181

Table I. (cant nued) Study Purpose Des gn Samp e F nd ngs Summary Hunter (20 I I ) Schaeffer, Leventha , and Asnes (2011) they d sc ose to, and what were the r mot yes for d Sc os ng A m of th s study was to deve op a fu er understand ng of CSA d sc osures Th s study a med to: (I) add d rect nqu ry about the process of a ch d's CSA d sc osure; (2) determ ne f ch dren w d scuff process that ed them to te : and (3) descr be factors that ch dren dent fy that ed them to te about or caused them to de ay CSA d sc osure data, sexua v ct m sat on. genera . and menta hea th. Sexua Assau t Modu e of the Juven e V ct m sat on Quest onna re was used Narrat ve nqu ry methodo ogy. Face-to- face n-depth ntery ews were conducted w th part c pants. Data were ana yzed us ng Rosentha and F scher— Rosentha 's (2004) method. Study sought to f nd out f process flues of d sc osure cou d be dent f ed n the context of forens c ntery ews. Forens c ntery ewers were asked to ncorporate quest ons about "te ng" nto an ex st ng forens c ntery ew protoco Intery ew content re ated to the ch dren's reasons for te ng or wa t ng was extracted, transcr bed, and ana yzed us ng grounded theory method of ana ys s commun ty and counse ng sery ces Purpos ye samp ng was emp oyed. Samp e cons sted of 22 part c pants aged 25- 70 years: 13 women and 9 men. Part c pants were sexua y abused at IS years or under w th someone over the age of It 191 ntery ews of CSA v ct ms aged 3-18 over a -year per od were used for the study. Inc us on cr ter a nc uded ch dren who made a statement about CSA pr or to refers. reasons for te ng or wa t ng to te , and those who spoke Eng sit. Part c pants were ch dren who were ntery ewed at a ch d sexua abuse c n c. 74% were ferna e and 51% were Caucas an not to burden them. Ear er d sc osures were re ated to extrafam a CSA, s ng e occurrence CSA, age of v ct m at abuse onset, and parents who were v ng together. H gher eves of reported gu t and shame were re ated to de ayed d sc osures. Peers were v ewed by th s samp e as more re ab e con( darts On y 5 out of 22 part c pants to d anyone about the r ear y sexua exper ences as ch dren. Fear, shame, and se f-b ame were the man nh b ton to d sc osure. These factors are further dem ed through subthemes. Te ng as a ch d and as an adu t was further expanded upon us ng A agg a's (2004) framework ver fy ng behav on nd rect attempts to te and purposefu d sc osure as categor es. Themat c ana ys s supported that CSA d sc osure shou d be conceptua zed and v ewed as a comp ex and fe ong process Reasons the ch dren dent fed for te ng were c ass fed nto three doma ns: (1) d sc osure as a resu t of nterna st mu (e.g. the ch d had n ghtmares): (2) d sc osure fac tated by outs de of uences (e.g. the ch d was quest oned): and (3) d sc osure due to d rect ev dente of abuse (e.g., the ch d's abuse was w tnessed). The barr ers to d sc osure dent f ed fe nto f ve groups: (I) threats made by the perpetrator (e.g.. the ch d was to d she or he wou d get n troub e f she or he to 4 (2) fears (e.g.. the ch d was afra d someth ng bad wou d happen f she or he to d), (3) ack of opportun ty (e.g., the ch d fe t the opportun ty to d sc ose never presented), (4) ack of understand ng (e.g.. the ch d fa ed to recogn ze abus ye behav or as unacceptab e), and (5) re at onsh p w th the perpetrator (e.g. the ch d thought the perpetrator was a fr end) research and bears more exam nat on De ayed d sc osure was common n th s qua tat ve samp e. Most part c pants d d not make a se ect ve d sc osure unt adu thood. These f nd ngs support A agg a's (2004) mode of d sc osure but a so h gh ghts the mportance of fe stage. Modest but suff c ent samp e s ze for a qua tat ve nqu ry. We -des gned study w th dem ed ana ys s for transferab ty off nd ngs An nnovat ve study to try to assess f forma nvest gat ye ntery ews can fac tate d sc osures of CA. Data were based on a arge number of ntery ews. Dem ed ana ys s produced dem ed f nd ngs support ng other study f nd ngs on CSA d sc osure (continued) EFTA00024181

Page 8 - EFTA00024182

I-, Table I. (coin nued) cr. P Study Purpose Des gn Samp e F nd ngs Summary A agg a (2010) Fontes and P ummer (2010) Ungar, Barter. McConne . Tutty, and Fa rho m. (2009a) The study a med to dent fy factors mped ng or promot ng CSA d sc osures. Overarch ng research quest on: What nd v dua, nterpersona . env ronmenta . and contextua nf uences mpede or promote CSA d sc osures. Th s exam nat on of CSA d sc osure exp ored the ways cu ture affects processes of CSA d sc osure and report ng. both n the Un ted States and nternat ona y Th s study exp ored d sc osure strateg es w th a nat ona sampe of youth focus ng on A qua tat ve phenomeno og ca des gn, LIM, was used to ntery ew adu t CSA sury von about the r d sc osure exper ences to prov de retrospect ve accounts of CSA d sc osure and mean ng-mak ng of these exper ences. Themat c ana ys s was done through a soc a — eco og ca ens. Us ng pub shed terature wthc nca data, th s art c e conducted an ana ys s to prov de a cu tura y competent framework for CSA d sc osure quest on ng Forms were comp eted by youth fo ow ng pan c pat on n abuse prevent on Purpos ye samp ng was emp oyed. Snowba samp ng was a so used to recru t more ma e sury von. 40 adu t sury von of CA were ntery ewed: 36% men and 64% women. Age range of 18-65 w th a mean age of 40.1 years. Average age of abuse onset was 5.3 years o d. 36% of the samp e was non-Wh te. D verse soc oeconom c backgrounds Data cons sted of pub shed terature on d sc osure and cu ture that was tr angu ated wthc n ca case mater a Exam nat on of resu is from a nat ona sampe of 1,621 eva uat on forms where youth Themes fe nto four doma ns: (I) nd v dua and deve opmenta factors, deve opmenta factors as to whether they comprehended what was happen ng, persona ty tra is a so had some bear ng on the r ab ty to te . and ant c pat ng not be ng be eyed; (2) d sc osure nh b ted by fam y character st cs such as rgdy fxed gender ro es w th dom nat ng fathers, chaos and aggress on. other forms of ch d abuse, domest c v o ence. dysfunct ona commun cat on. and soc a so at on; (3) ne ghborhood and commun ty context. that s. ack of nterest from ne ghbors and teachers not pursu ng troub ng behav or; and (4) cu tura and soc eta an tudes, med a messages and soc eta an tudes. fee ng unheard as k ds, gender soc a zat on for ma es. and cu tura an tudes of uenc ng parent's react ons. Purposefu d sc osure s h gher than reported n other stud es because of the samp ng attempts to purposefu y ocate d sc osers Cu tura and structura factors affect ng CSA d sc osure are dent f ed n n-depth deta Recommendat ons made nc ude ( I) d sc osure ntery ew ng shou d be ta ored to the ch d's cu tura context. (2) quest on ng shou d a so take nto cons dent on age and gender factors. and (3) cu ture stands as an mportant factor n a cases n wh ch ch dren are cons der ng d sc os ng or be ng asked to d sc ose. and not so e y n cases nwh ch ch dren are from not ceab e m nor ty groups. Presents a comprehens ye ntery ew framework ntegrat ng cu tura cons dent ons Youth who have been abused or w tnesses to abuse emp oy f ve d sc osure strateg es: us ng se f-harm ng behav on to s gna the abuse to others; not ta k ng The study presents a comprehens ve soc a —eco og ca ana ys s to CSA d sc osure h gh ght ng the mu t faceted of uences. Of note, 42% had d sc osed the abuse dur ng ch dhood: 26% had not d sc osed because they had repressed the memory, or the abuse had occurred n preschoo years and they had d dal ty w th reca . The rema nder had attempted some form of d sc osure n nd rett ways dur ng ch dhood. A retrospect ye approach that cou d be affected by reca ssues One of the few works that adds know edge to cu tun y contextua d sc osure ntery ew ng. Un que comb nat on of teraturefnd ngswthcn ca mater a . Anecdota accounts may prec ude transferab ty of f nd ngs. Oven adds to an mpover shed area of CSA d sc osure nformat on Th s study h gh ghts that d sc osure s an nteract ye ongo ng process. F nd ngs end support to stud es that have dent f ed s mar y (continued) EFTA00024182

Page 9 - EFTA00024183

Table I. (cont nucd) Study Purpose Des gn Samp e F nd ngs Summary (I) What are the h dden exper ences of abuse among Canad an youth? (2) What mpact does part c pat on n abuse prevent on programs have on youth to express the r abuse exper ences? (3) What d sc osure barr en do youth face? (4) What are young peop es d sc osure patterns? and (5) Who do they to ? Ungar, Tutty. McConne . Th s study exp ored Barter, and Fa rho m abuse d sc osure (20096) strateg es w th a nat ona samp e of Canad an youth who part c paced nvoence prevent on programm ng. One of the goa s of the study was to document not prey ous y dent f ed exper ences of abuse and youth att tudes toward d sc osure of abuse exper ences program ng by the Canad an Red Cross (RespectED). A ser es of focus groups and observat ons of the workshops were used to he p contextua ze the f nd ngs. Eva uat on forms were ana yzed from two v o ence prevent on programs: ( I) It's not your fau t and (2) What's ove got to do w th It? Exp oratory des gn w th a nonrepresentat ve samp es. Qua tat ye ana ys s of 1,099 eva uat on forms comp Ned fo ow ng Red Cross RespectED v o ence prevent on programm ng de vered between 2000 and 2003. Forms of anonymous abuse d sc osures by youth pan c pants of neg emot ona phys ca . and sexua abuse. Twenty-seven ntery ews and focus groups were a so done to understand contextua ssues and engage youth and program fac tators n the nterpretat on of f nd ngs. A cod ng structure was deve oped for ana ys s to synthes ze themes across data sources anonymous y d sc osed abuse exper ences. Respondent's ages: 13 and under (27%). 14- IS (37%), 16-17 (25%). 18 and o der (4%), and unknown (7%) Purposefu samp e of 1,099 eva uat on forms comp eted fo ow ng Red Cross RespectED v o ence prevent on programm rig de vered between 2000 and 2003 at a about the abuse to prevent ntrus ve ntervent ons by others; seek ng he p from peers; seek ng he p from nforma adu t supports: and seek ng he p from mandated sery ce prov den (soc a workers and po ce). Resu is suggest d sc osure s an nteract ye process, w th expectat ons regard ng consequences to d sc osure. Patterns of ncrementa y char ng abuse exper ences are shaped by young peop e's nteract ons w di peers, educators, and careg vers. About three- quarters of fema es prey ous y d sc osed: s gn f cant y ess ma es d sc osed F nd ngs suggest h gh rates of h dden abuse, w th ess than one quarter of youth report ng a d sc osure. 244 of the 1,099 youth who d sc osed abuse on the r eva uat on forms dent fed spec f c nd v dua s they to d about the r abuse. D sc osure patterns vary w th boys, youth aged I4-15, v ct ms of phys ca abuse, and those abused by a fan y member be ng most ke y to d sc ose to profess ona s or the po ce. One th rd of d sc osures were d rected toward profess ona s and the east. 5% percent each, were d rected toward fr ends, parents. and others. Part c pants were most ke y to d sc ose sexua abuse to parentsffam y. profess ona s. and the po ce/courts. w th fewer choos ng fr ends. Out of a 1.099 part c pants, 225 ma es and 779 fema es nd cated that they had been abused. Out of those. 43 ma es and 180 fema es nd cated that they had d sc osed the abuse. Of those who had d sc osed, on y a port on of ma es and fema es spec fed who they had d sc osed the abuse to c'VVh e 1.099 eva uat ons w th d sc osure statements were ana yzed. on y 22% made ment on of peop e to nteract ye modes of d sc osure such as those deta ed by A agg a (2004) and Sta er and Ne son- Garde (2005). Th s m xed samp e of youth who exper enced d fferent forms of abuse and v o ence exposure were part c pants—not in ted to CSA SW, / vors Innovat ve des gn of th s study prov des ns ght nto young peop es percept ons of d sc osure exper ences. H gh eve of r gor w th trustworth ness of the data ana ys s ensured through use of youth focus groups. ntery ews. and observat ona data. The study resu is are somewhat m ted n the th ckness of the descr pt ons t can offer because most of the data are survey based. Reg ona d fferences may not have been p cked up. Scope of the study s broad and approach s treat ve (continued) EFTA00024183

Sponsored

Page 10 - EFTA00024184

Table I. (cont nued) ao Study Purpose Des gn Samp e Fnd ngs Summary Pr cbc and Svcd n (2008) Th s study a med to nvest gate d sc osure rates and d sc osure patterns and exam ne pred ctors of nond sc osure n a samp e of ma e and fema e ado escents w th se (-reported exper ences of sexua abuse Sorso , K a-Keat ng, and Grossman (2008) Study focused on d sc osure cha ences for ma e sury von of CSA to understand three ssues: (I) To Part c pants competed 65- tern quest onna re that nc uded quest ons about background, consensua sex. sexua abuse exper ences (noncontact, contact or penetrat rig abuse, nc ud ng peer abuse), d sc osure of CSA, own sexua abus ve behav or. sexua att tudes. and exper ences w th pornography and sexua exp o at on. The quest onna re nc uded 6 mod( ed terns from the SCL-90 and 9 of 25 tems from the Parenta Bond ng Instrument_ The data for g r s and boys were ana yzed separate y Ma e sun von of CA were ntery ewed about the r d sc osure exper ences. Ana yt c techn ques nc uded The samp e cons sted of 4,339 h gh schoo students n Sweden (2,324 g r s and 2,0 I 5 boys). The mean age of the part c pants was 18.15 years. Th s study used a subsamp e of 1,962 part c pants who reported CSA and who answered d sc osure quest ons The samp e cons sted of 16 ma e sury vors of ch dhood sexua abuse; I I Caucas an, 2 Afr can Amer can. I whom d sc osures occurred.") More fema es spec fed who they d sc osed to compare to ma es. The data show percept ons among youth of negat ve consequences fo ow rig d sc osure Of the samp e, 1.505 g r s (65%) and 457 boys (23%) reported CS& The d sc osure rate was 81% (g r s) and 69% (boys). G r s and boys d sc osed most often to a fr end of the r own age. Few had d sc osed to profess ona s. and even fewer had reported to the author t es. There were h gher rates of d sc osure to a profess ona w th more severe abuse (contact abuse w th or w thout penetrat on) for g r s. but ower rates for boys The more severe the sexua abuse was, the ess key both g r s and boys had ta ked to the r mother, father. or a s b ng. G r s were ess ke y to d sc ose f they had exper enced contact sexua abuse w th or w thout penetrat on. ess frequent abuse, abuse by a fam y member, or f they had perce ved the r parents as ess car rig and ess overprotect ve and h gh y overprotect ve. Boys were ess key to d sc ose f a fam y member abused them, they were study ng a vocat ona program (vs. an academ c program), ved w th both parents or had perce ved the r parents as ess car rig and not overprotect ve. Ado escents who reported CA perce ved the r menta heath as poorer compared to ado escents w thout CS& Nond sc osers reported more symptoms on the Mena Heath Sca e than those who had d sc osed Barr en to d sc osure were found to be operant n three nterre aced doma ns: (I) persona (e.g.. ack of cogn t ve awareness. ntent ona avo dance, emot ona read ness. and shame); (2) Th s study h gh ghted that sexua abuse s arse y h dden from adu t soc ety. espec a y from profess ona s and the ega system. However. t me apsed to d sc osure was not reported. S nce fr ends appeared to be the man rec p ents of sexua abuse d sc osures, pract ce mp cat ons of th s cou d be to f nd ways to g ye young peop e better nformat on and gu dance about how to support a sexua y abused peer. A qua tat ve component to the study wou d have prov ded a broader understand ng of d sc osure processes. Study m tat ons nc ude a s gn f cant amount of boys who d d not comp ete the quest ons regard rig d sc osure on: the t m rig of d sc osures (whether they were de ayed or not) was not measured: poss b ty of reca b as w th retrospect ve stud es based on se (-reports; and youth part c pants may not have understood a the quest ons S nce the vast major ty of men n the samp e had not d sc osed n ch dhood, they may have been pred spored to dent fy ng barr ers to d sc osure more (continued) EFTA00024184

Page 11 - EFTA00024185

Table I. (cont nued) Study Purpose Des gn Samp e F nd ngs Summary Hershkow tz. Lanes, and Lamb (2007) whom and n what contexts have they d sc osed these exper ences? (2) What do they have to say about the r d sc osure exper ences? and (3) What are the r percept ons of pos t ve and negat ye aspects of the r d sc osure. nc ud ng ncent ves and barren? The goa of the present study was to exam ne how ch d v ms of extrafam a sexua abuse d sc osed the abuse exper ence grounded theory method of ana ys s for cod ng and deve opment of conceptua y c ustered matr ces. Part c pants comp eted two n- depth, sem -structured ntery ews, ast ng between 2 and 3 hr each tak ng p ace approx mate y a week apart A eged v a ms of sexua abuse and the r parents were ntery ewed. Ch dren were ntery ewed us ng the NICHD Invest gat ve Intery ew Protoco by exper enced youth nvest gators. Informat on on d sc osure processes was obta ned n the f rst forma ntery ew, before any po ce nvest gat on or ch d we fare ntervent on Puerto R can. I part Nat ve Amer can, Afr can Cuban: age range of 24-61 years; 9 dent fed themse yes as heterosexua, 5 as homosexua, and 2 as b sexua Th ny a eged v ct ms of CSA: 18 boys and 12 g r s. Ch d samp e was 7- to I2-year-o ds w th an avenge age of 9.2 years. Twenty mothers and 10 fathers were a so ntery ewed for a tota of 30 parent ntery ews. A content ana ys s was conducted on ch d and parent ntery ews re at ona (e.g.. fears about negat ve repercuss ons. so at on); and (3) zoc ocu tura (e.g., ack of acceptance for men to exper ence or acknow edge v ct m zat on). On y I of the 16 men n th s samp e d sc osed the fu extent of h s sexua abuse exper ences wh e he was st a ch d. The other men reported that they had not d sc osed. a though some reported attempts to to that were nd rect or ncomp ete. Seven other men d sc osed terra n exper ences or e ements of the r abuse, but concea ed others. By the t me of the study. many of these men had d sc osed the r past exper ences n a var ety of re at onsh nc ud ng those w th fam y members, partners. therap sts, and nfrequent y fr ends. Seven had on y m ted d scuts ons of the r sexua abuse D sc osure categor es were dent fed as fo ows: (I) de ayed 53% of the ch dren de ayed d sc osure for between I week and 2 years: (2) rec p ent of d sc osure: 47% of ch dren f rst d sc osed to s b ngs or fr ends, 43% f rst d sc osed to the r parents. and I0% f rst d sc osed to another adu t. 57% of the ch dren spontaneous y d sc osed abuse, but 43% d sc osed on y after they were prompted. 50% of the ch dren reported fee ng afn d or ashamed of the r parents' responses. Parents' react ons: support ve (37%) and unsupport ve (63%). There was a strong corre at on between pred cted and acwa parenta react ons suggest ng ch dren ant c pated the r parents' ke y react ons accurate y. D sc osure processes var ed depend ng on the ch dren's ages (e.g.. younger ch dren d sc osed to parents). sever ty and frequency of abuse, parents' expected react ons, suspects' dent t es, and strateg es used to foster secrecy read y. Retrospect ve accounts are subject to reca ssues. Invest gators made s gn f cant efforts to gather a d verse samp e. H gh eve of r gor was executed n the dependab ty of the data and tent ve process of the nterpretat on of f nd ngs was conducted Innovat ve des gn to gather d sc osure data from young ch dren. Focus s on extrafam a CA wh ch may d Her than d sc osure patterns of ntnfam a CSA. Two th rds of the parents reg stered unsupport ve responses wit ch s h gh rconunuedt EFTA00024185

Page 12 - EFTA00024186

Table I. (cont nued) •-•1 Study Purpose Des gn Samp e F nd ngs Summary A agg a and K rshenbaum The object ves of the (2005) current study were to dent fy a broad range of factors, nc ud ng fam y dynam cs that corn bute to or h nder a ch d's ab ty to d sc ose CSA. A au a (2005) Co ngs, Gr ff ths. and Kuma o (2005). The study purpose was to qua at ve y exp ore dynam cs that mpede or promote d sc osure by exam n ng a range of factors nc ud ng gender as a dynam c— how d sc osures of fema es and ma es are s m ar and d fferent. and n what ways gender affects CSA d sc osure Study exam ned patterns of d sc osure n a arge represent ve samp e of South Afr can CSA v ct ms. Two study object ves to: ( I ) exam ne how and A qua tat ve phenomeno og ca des gn—LIM—was used toe c t d sc osure exper ences: fac tators and barr en: and re evant c rcumstances. Intery ews were transcr bed verbat m. L ne-by- ne open cod ng was conducted to capture fam y- eve factors. Ax a and se ect ve cod ng fac tated dent f at on of themes Sury von of CSA were ntery ewed about the r d sc osure exper ences us ng LIM. Ana ys s of 30 part c pant narrat ves was used for theme deve opment regard ng mpact of gender on d sc osure. Intery ews were transcr bed verbat m for open. ax a . and se ect ve cod ng. Categor es and subcategor es were co apsed and ref n ng nto theme areas F e rev ews of a soc a work and med a case f es for CSA v ct ms seen at the cr s s center where a cases of CSA reported to the North Durban Purpos ye samp ng was emp oyed to recru t 20 adu t sun von between the ages of and 65 who were sexua y abused by a fam y member. Average age of part c pants was 40.1 years: 60% of part c pants were fema e and 40% ma e. Avenge age of onset of abuse was 6.7 years. M xed c n ca and nonc n ca samp e. The major ty had rece ved treatment for CSA at some po nt n the r ves Purpos ve samp ng of women and men. a ong w th those who d sc osed dur ng the abuse and those who d d not. I9 fema es and II ma es; 18-65 (mean 40.1) years who were sexua y abused by a fam y member or a trusted adu t. Avenge age of abuse onset was 5.3 years, 36% were nonwh te, and 58% had not d sc osed dur ng ch dhood 1.737 cases of CSA reported n the North Durban area of KwaZu u-Nata . South Afr ca, dur ng January 2001 to December 2003. 1,614 grs and Four major themes emerged suggest ng that CSA d sc osure can be s gn f cant y comprom sed when certa n fam y condtons ex st (I) rg dy f xed, gender ro es based on a patr archy-based fain y structure; (2) presence of fam y v o ence; (3) c osed, nd rect fam y commun cat on patterns; and (4) soc a so at on of the fam y as a who e, or spec f c members, payed a part n CSA v ct ms fee ng they had no one safe to te . Fam y systems formu at ons through a fem n st ens are mportant n understand ng ch dren and fam es at r sk of d sc osure barr en Three themes emerged for men that nh b ted or prec p tated d sc osure for reasons re ated to gender: (I) fear of be ng v ewed as homosexua : (2) profound fee ngs of st gmat zat on or so at on because of the be of that boys are rare y v ct m zed; and (3) fear of becom ng an abuser, wh ch acted as a prec p cant for d sc osure. Two predom nant themes w th fema e part c pants re ated to d ff cu t es d sc os ng: (I) they fe t more conf cted about who was respons b e for the abuse and (2) they more strong y ant c paced be ng b amed and/or not be eyed Content ma ys s dent fed two broad d mens ons of d sc osure: (I) agency: ch d- n t aced d sc osure versus detect on by a th rd party and (2) tempon durst on: an event versus a process. These d sc osure d mens ons def ned four d screte categor es of Over ha f the part c pants had not d sc osed the abuse dur ng ch dhood. Of the nond sc os ng part c pants, s x d d not d sc ose because they had repressed or forgotten the memory. A most one th rd w thhe d d sc osure ntent ona y. More data are needed on ear y d sc osures to garner more nformat on on fac atop of d sc osure. Retrospect ye approach mp es reca ssues. H gh eve of trustworth ness of the data and nterpretat ons were ach eyed through cred b ty. dependab ty. and conf rmab ty through d rect quotes One n a dearth of stud es that conduct gender ana ys s. Comparat ye ana ys s draws out mportant pract ce mp cat ons. Retrospect ve des gn of the study wh ch mp es poss b e reca ssues. Hgh eve of trustworth ness of the data and nterpretat ons were ach eyed through cred b ty. dependab ty. and conf rmab ty through d rect quotes These resu tsft nto A agg a's (2004) d sc osure framework. Through data ana ys s two raters coded d sc osure categor es us ng author's d sc osure framework, wh ch proved to be both exhaust ve and mutua y exc us ve (continued) EFTA00024186

Sponsored

Page 13 - EFTA00024187

Table I. (cone nued) Study Purpose Des gn Samp e F nd ngs Summary when CSA v ct ms d sc ose the r abuse and (2) Ident fy factors assoc ated w th d fferent patterns of d sc osure po c ng area were referred dur ng the per od of January 2001 to December 2003 123 boys: average age of v ct m zed ch dren was 9.9 years. 47% reports were made w th n 72 hr of the abuse, 31% from 72 hr to I month, and 22% more than a month after the abuse d sc osure: (I) purposefu d sc osure (30% of cases), (2) nd rect d sc osure (9% of cases), (3) eyew tness detect on (18% of cases), and (4) acc dents detect on (43% of cases). D sc osure ndependent y pred cted by v a m's age. nature of the v ct m—perpetrator re at onsh p. offender's age. frequency of abuse. and report ng atency. Mean age of purposefu d sc osures (10.67) was h gher than the mean age of nd rect d sc osures (5.84). Exp c t forms of d sc osure were ess ke y when the offender was a fam y member. Shorter w th the percentage of nternter agreement at 98%. Genera zab ty of th s study s m ted to ch d o ents rece v ng a cr s s assessment referred through a po ce report report ng atency was more key w th repeated abuse Hcrshkow a, Horow Th s study a med to Large database of The camp e was Oven , 65% of the 26,446 ch dren made Oven f nd ngs nd cated that rates and Lamb (2005). dent fy character st cs suspected cases of compr sed of 26.446 of a egatons when ntery ewed. Rates of of d sc osure var ed systemat ca y of suspected ch d phys ca and sexua 3- to14-yearn d d sc osure were greater for sexua abuse depend ng on the nature of the abuse v a ms that are abuse nvest gated n a eged v ct ms of (71%) over phys ca abuse (61%). a eged offences. the re at onsh p assoc ated w th Is ne between 1998 sexua and phys ca Ch dren of a ages were ess key to between a eged v a ms and d sc osure and and 2002 was ana yzed. abuse ntery ewed n d sc osela ege abuse when a parent was suspected perpetrators. and the nond sc osure dur ng Intery ews were a so Israe n the 5-year the suspected perpetrator. D sc osure age of the suspected v a ms. forma nvest gat ons conducted us ng per od from 1998 to rates ncreased as ch dren grew o der. Ana yses on y mo ved cases that standard zed NICHD 2002. 140 exper enced 50% w th 3- to 6-yearn ds. 67% of the 7- had come to the attent on of Invest gat ve Intery ew toned youth to I0-year-o ds. and 74% of the I I- to off c a agenc es. mak ng t d ff cu t Protoco . Arch va data nvest gators I4-year-o ds d sc osed abuse when to determ ne how many of abuse were ana yzed conducted ntery ews quest oned take p ace w thout ever tr gger ng any k nd of off c a nvest gat on Jensen. Gu brandsen, Th s study nvest gated Qua tat ve approach to 20 fam es w th a tota of None of the ch dren to d of abuse Ev dence for de ayed d sc osures. Moss ge, Re the t. and the context n wh ch data co ect on and 22 ch dren mmed ate y after t occurred. Ch dren The resu is nd ate that Tjers and (2005) ch dren were ab e to ana ys s was used. part c pated. A exposed to repet t ye abuse kept th s as a d sc osure s a fundaments y report the r ch d Therapeut c ntery ews ch dren had to d about secret for up to seven years: 17 to d d a og a process that becomes sexua abuse o the ch dren and exper ences that the r mothers f rst, 3 f rst to d a fr end. ess d ff cu t f ch dren perce ve exper ences: the r most y the r mothers created concerns for to d the r father, and I the r unc e. that there s an opportun ty to v ews as to what made were ana yzed through care-g vers about CSA. Major ty of remarks that ed to the ta k. a purpose for speak ng and a t d ff cu t to ta k about a qua tat ve approach. Ch dren's ages ranged susp con of CSA were made n connect on has been estab shed abuse: what he ped Fo ow-up ntery ews between 3 and 16 s tuat ons where someone engaged the to what they are ta k ng about. them n the d sc os ng were he d I year ater years (average age 7.5 ch d nada ogue about what was Strengthen ng parent ch d process: and the r years): 15 g r s and 7 bother ng them, resu t ng n a referra re at onsh ps s an mportant parent's percept ons of the r d sc osure processes boys. Sexua y abused by someone n the tam y or a c ose person to the fam y The ch dren fe t t was d ff cu t to f nd s tuat ons conta n ng enough pr vacy and prompts that they cou d share the r exper ences. When the ch dren d d pact ce mp cat on ICOtitinUed) EFTA00024187

Page 14 - EFTA00024188

Table I. (coot nued) Study Purpose Des gn Samp e F nd ngs Summary Sta er and Ne son- Garde (2005) A agg a (2004) The purpose of th s study was to understand the fu process of CSA d sc osure and how th s unfo ded for preado escent and ado escent g r s. Exam ned what fac tated and h ndered d sc osure and subsequent consequences The study sought to exam ne nf uences that nh b t or promote ch dren's d sc osure of CSA to address gaps n know edge about how, when, and under what c rcumstances v a ms of CSA d sc ose Secondary ana ys s of qua tat ve focus group data. Or g na project cons seed of four focus groups conducted w th n the context of ongo ng therapy for g r s who had exper enced CSA. Secondary am ys s cons seed of wr tten narrat ye summar es of each secs on group ng these conceptua y, and exam n ng the r nterconnectedness The study emp oyed LIM—a phenomeno og ca des gn. Intens ve ntery ew ng that were 2 hr ong on average generated data for a themat c am ys s. The ntery ew gu de was Samp e cons seed of 34 part c pants from four groups. Sess ons ana yzed were between 60 and 90 m n ong: and otaped and ater transcr bed for content am ys s Us ng purpos ye samp ng 24 adu t sun von of ntnfam a abuse between ages of 18 and 65 (average age 41.2) were recru ted from agent es and one un vers ty: 57% ma e and 43% fema d sc ose they d d t n s wat ons where the top c of ch d sexua abuse was n some form addressed or act vated. where someone recogn zed the ch d's cues and probed further. They a so were sens t ve to others react ons, and whether the r d sc osures wou d be m s nterpreted. Seven of the ch dren perce ved negat ve consequences as major factors contr but ng to de ay ng d sc osure. They were pr mar y concerned about negat ve effects for the mother. The mothers sad they were a so sens t ve to the ch dren's fee ngs. If the r ch dren showed s gns of d stress and d d not want to ta k. the mothers wou d change the subject or not pursue the top c further F nd ngs are reported n three major doma ns: ( I ) se (-phase: where ch dren come to understand v ct m at on nterna y (2) conf dant se ect on- react on phase: where they se ect a t me, p ace, and person to te and then whether that person's react on was support ve or host e: and (3) consequences phase: good and bad that cone nued to nform the r ongo ng strateg es of te ng. The act ons and react ons of adu is were s gn f cant and nformed the g r s' dec s ons. The consequences phase was further subd v ded nto four aspects: (I) Boss p ng and news networks, (2) chang ng re at onsh ps, (3) nst tut om responses and the after fe of te ng. and (4) ns der and outs der commun t es Through ana ys s of the ntery ew new categor es of d sc osure were dent fed to add to ex st ng types. Three prey ous y dent f ed were conf rmed n these data: acc denta purposefu . and prompted!e c ted accounted for 42% of d sc osure patterns n the study samp e. Over ha f the d sc osure patterns descr bed by the study samp e d d not f t these Th s study prov ded a contextua exam nat on of the ent re d sc osure process. c oser to the po nt n t me when the abuse and d sc osure occurred. Sma groups of preado escent and ado escent g r s who had sury ved sexua abuse a so served as consu tants and were encouraged to share the r know edge for the benef t of profess ona prate t oners Th s study expanded types of CSA d sc osures to more fu y understand how ch dren and adu is d sc ose. And under what c rcumstances. Ask ng peop e to recount events that occurred n ch dhood s suscept b e to memory ft ure. espec a y when memor es were forgotten. (continued) EFTA00024188

Page 15 - EFTA00024189

Table I. (tont nued) Study Purpose Des gn Samp e F nd ngs Summary Cr sma, Basce , Pac. and The ma n goa s of th s Rom to (2004) study were to understand mped menu that prevent ado escents from d sc os ng CSA and seek ng he p from the r soc a network and/or the sery ces Jonzon and L ndb ad Study purpose was to (2004) exp ore how abuse tra ts. openness, react ons to CSA d sc osure. and soc a support were re ated. D fferences based on sever ty of abuse. t m ng and outcomes of d sc osure. soc a support. and pred a ng factors of pos t ve and negat ve react ons were probed deve oped to probe for nd v dua , nterpersona . env ronmenta . and cu tura factors of uenc ng CSA d sc osure In-depth to ephone (anonymous) ntery ews were conducted after nformed consent was exp a ned and obta ned. Three nvest gators exper enced n counse ng CSA counse ng conducted the ntery ews wh ch were recorded w th perm ss on. Three researchers ndependent y scored the ntery ews accord ng to a cod ng framework Adu t women report ng CSA by someone c ose were ntery ewed us ng sem -structured gu des together w th quest onna res. Data on v a m zat on and current soc a support were retr eyed through the quest onna res, and data on d sc osure and react ons were gathered through the ntery ews w th part c pants average age of abuse onset was 6.5 years: 42% of the part c pants had d sc osed the abuse dur ng ch dhood: 58% d sc osed as adu is The samp e was compr sed of 36 young peop e who exper enced sexua abuse n ado escence: 35 fema es and I ma c aged 12-17. Some of the samp e exper enced sexua v o ence n a dat ng re at onsh p 122 adu t women between 20 and 60 years o d (average age of 41 years) report ng exposure to ch d sexua abuse by someone c ose before the age of I8 and had to d someone about at east one abuse event 90% were Swed sh subjects. Purpos ve samp ng strategy was used prey ous y estab shed categor es. Three add t ona d sc osure categor es emerged: behav ora and nd rect verba attempts. d sc osures ntent ona y w thhe d. and d sc osures tr ggered by recovered memor es The ma n mped menu to d sc ose to a fam y member were: fear of not be ng be eyed, shame, and fear of at ng troub e to the fam y. The ma n mped menu for not seek ng sery ces were: unaware of appropr ate sery ces. w sh to keep the secret. ack of awareness of be ng abused, m strust of adu ts and profess ona s. and fear of the consequences of d sc os ng sexua abuse. When they d d d sc ose to profess ona s. teens rece ved very m ted support as many profess ona s were not tra ned on sexua abuse and cou d not offer appropr ate ntervent ons co v ct ms Abuse character st a: abuse by mu t p e perpetrators was more common than by a s ng e perpetrator. Age of onset was often before age of 7. w th an average durat on of 7 years. Severe y abused women had to ked to more of the r soc a network. espec a y to profess ona s. D sc osures: 32% d sc osed dur ng ch dhood (before the age of 18) w th an average of 21 years de ay. Women who had d sc osed n ch dhood reported more nstances of phys ca abuse, mu t p e perpetrators. use of v o ence, and were more ke y to have confronted a perpetrator, and had rece ved a negat ve f rst react on. Factors de ayed. or repressed and ater recovered. D stop on and rev s on of events are a so potent a prob ems nreca . H gh degree of trustworth ness of the data was ach eyed and quotes prov ded supported the categor es Th s study represented the f nd ngs of a m xed samp e of sun von of ch d sexua abuse and nt mate partner v o ence. The study was conducted n Ita y and t s not c ear what sexua abuse response tra n ng s an ab e. There may have been a se ect on b as as the most d scat sf ed sury vors responded to the research ca 68% de ayed d sc osure unt adu thood. At the t me of the study, t was one of the f rst stud es to focus on the nterp ay between soc a support networks and d sc osure of ch d sexua abuse. The study resu u are somewhat m ted by an overrepresentat on of severe y abused women. Retrospect ve study and se f-report of nformat on cou d mp y reca ssues and thus m ts the accuracy of the nformat on obta ned on abuse and d sc osure character st a. Cross-sect ona (continued) EFTA00024189

Sponsored

Page 16 - EFTA00024190

;el a. Table I. (cont nued) Study Purpose Des gn Samp e F ndngs Summary Kogan (2004) Goodman-Brown, Ede ste n. Goodman. Jones, and Gordon (2003) The purpose of th s study was to dent fy factors that of uence the d sc osures made by fema e sury vors of USE n ch dhood and ado escence. The pred tears of both the t m ng of d sc osure and the rec pent of the d sc osure were nvest gated The purpose of th s study was to nvest gate var ab es assoc ated w th de ay of d sc osure of CSA and test a mode for factors that of uence how qu ck y ch dren d sc ose sexua abuse Data were gathered from a subsamp e of fema e ado escents that part c pared n the NSA, wh ch cons sted of structured phone ntery ews. USES reported n the NSA were assessed us ng a mod f ed vers on of the Inc dent C ass f cat on Intent ew. They were then asked a ser es of quest ons about each ep sode of unwanted sexua contact nc ud ng event character st a and perpetrator character st a Case f e rev ews of data obta ned from prosecut on f es, as we as from structured ntery ews w th the ch dren 's caretaker and observat ons of ch d ntery ews. Tn ned graduate students and one v ct m advocate comp eted the Sexua Assau t Prof e A subsamp e of 263 ado escent fema es between 12 and 17 years o d, mean age of 15.2 years o d, who reported at east one exper ence of unwanted sexua contact n the NSA. Part c pant character st a. USE character st a. and fam y contextua attr butes were exp ored Samp e cons sted of 218 dr dren referred to prosecutors' off ces for a eged CSA. A ch dren n the samp e had d sc osed the r abuse n some manner. Ch dren ranged n age from 2 to I6 years at the beg nn ng of abuse; 3-16 years at the end of the abuse, and 4-16 years at the t me of the s gn f cant y pred ct ng de ay were younger age at f rst event and no use of v o ence. D sc osure outcomes: of the 26 women who to d n ch dhood dur ng a per od w th ongo ng abuse, IS women were cont nuous y abused after d sc osure Ch dren under the age of 7 were at a h gher r sk for de ayed d sc osures. Part c pants whose USE occurred between the ages of 7 and 13 were most key to te an adu t. Ado escents (14- 17) were more ke y to te on y peers than ch dren aged 7-10 years. Ch dren under II were more ke y to te an adu t. but were at r sk for de ay ng d sc osure beyond a month. Ch dren aged II-13 tended to d sc ose w th n a month. C oser re at onsh p to the perpetrator or a fam y member was assoc ated w th de ayed d sc osure. Immed ate d sc osure was more ke y w th stranger perpetrat on. Fear for ones fe dur ng and penetrat on were assoc ated w th d sc osure to adu ts. Fam y factors nked to d sc osure were (I) drug abus ng househo d member, wh ch made sury von more key to d sc ose more prompt y and (2) never v ng w th both parents was assoc ated w th nond sc osure 64% d sc osed w th n a month and 29% w th n 6 months. F ve var ab es for the mode were tested. (I) age: ch dren who were o der took onger to d sc ose and o der ch dren feared more negat ve consequences to others than younger ch dren: (2) type of abuse: v ct ms of ntrafam a fam es took onger to d sc ose—v ct ms of ntrafam a abuse feared greater negat ye consequences to others compared to v ct ms of extrafam a abuse: (3) fear of negat ve consequences: ch dren who feared des gn does not a ow for def n te conc us ons of cause and effect on the re at onsh ps found Th s study exam ned factors nc ud ng d sc osures of USES n ch dhood and ado escence n a nat ona y representat ye samp e of fema e ado escents who part c pared n the NSA. Surveys for nvest gat ons of v ct m zat on exper ences may be b ased due to underreport ng. Ado escents who refused to report or d scuss an USE may represent a source of systemat c b as and wou d make the resu ts genera zab e on y to ado escents who are w ng to d sc ose USE v a survey. A though data may be retrospect ye, reca b as may have been m n m zed n th s study s nce part c pants were ado escents. and so the t me ag between the USE and the ntery ew were presumab y shorter than a study of adu t part c pants reca ng CSA exper ences Th s study represents a h gher rate of d sc osers w th n a month. These cases had been reported to author t es and were n process of prosecut on wh ch may exp a n h gher rate of ear y d sc osures. Lega samp e w th h gher rate of extrafam a abuse (52%) may a so account for ear er d sc osures. Mode suggests that o der ch dren, v ct ms of ntrafam a abuse: fe t greater respons b ty for the abuse, and perce v ng (continued) EFTA00024190

Page 17 - EFTA00024191

Table 1. (coot nued) Study Purpose Des gn Samp e F nd ngs Summary Sm th. Letourneau. Saunders, K paw ck. Resn ck and Best (2000) The study focus was to gather data from a arge samp e of women about the ength of t me women who were raped before age 18 de ayed d sc osure who they d sc osed to. and var ab es that pred cted d sc osure w th n I month quest onna re for ch d character st cs. the abuse and the r d sc osure. Ch dren's percept on of respons b ty and fear of negat ve consequences were probed. Corre at ona ana yses were conducted w th path ana yses to test the hypothes zed causa re at ons among var ab es Structured te ephone ntery ews that asted approx mate y 35 m n were used to co ect data us ng a computer- ass sted te ephone ntery ew system. A te ephone ntery ews were conducted w th each quest on on a computer screen. The survey cons sted of seven measures des gned toe ct demograph c nformat on. psych atr c symptoms. substance use, and v ct m zat on h story. The present study reports on data from the demograph c and ch d rape v a m zat on quest ons n t a po ce report: 77% fema e. 70% Caucas an. 17% H span c. and I I% Mr can Amer can. Predom nant y m dd e to ow SES. Approx mate y 47% ntrafam a abuse Two probab ty samp es. Wave I was a random samp e of 2.009 respondents se ected from stmt fed samp es of def ned jur sd ct ons. Random d g ta d a rig was used to so c t househo ds for seed and un seed te ephone numbers. Second random samp e of 2.000 women between the ages of 18 and 34 Was se ected. Both Wave I and Wave 2 data were we ghted to conform to the 1989 Census stat st a negat ve consequences of d se osure took onger to d sc ose, ch dren who be eyed that the r d sc osure wou d br ng harm to others took onger to d sc ose, fear of negat ye consequences to the se f or the perpetrator was unre ated to t me of d sc osure. and g r s more than boys feared negat ye consequences to others: (4) Perce ved respons b ty: ch dren who fe t greater respons b ty for the abuse took onger to d sc ose and o der ch dren fe t more respons b ty for the abuse: and (5) gender was not s gn f cant y corre ated w th t me to d sc osure 288 (9%) reported exper enc ng at east one event that met the study's def n t on of ch dhood rape. The average age at the t me of the f rst rape was 10.9 years. Of the 288 women who reported a ch d rape. 28% stated that they had never to d anyone about th s sexua assau t unt spec f a y quer ed by the ntery ewer for th s study. 58% d d not d sc ose for over 1 year and up to 5 years post-rape. 27% d sc osed w th n a month. Among women who d sc osed pr or to the r NWS ntery ew c ose fr ends were the most common person to whom v a ms made d sc °sures, fo owed by mothers and other mmed ate fam y members. Fewer than 10% of ir a ms reported mak ng the r nta dsc osure to soc a workers or aw enforcement personne . On y 12% of ch d rape v ct ms stated that the r assau is were reported to author t es at some po nt negat ve consequences to d sc os ng took onger to d sc on. We -des gned study w th h gh eve of r gor. Produced a v ab e mode of d sc osure for further nvest gat ons. However. researchers were not ab e to ntery ew ch dren d rect y The t me frame of th s survey may have had contextua mp cat ons. The major ty of ch d rapes reported by th s samp e occurred pr or to the arge-sca e ch d assau t prevent on educat on programs that were begun n the I 980s that teach ch dren that assau is ( nc ud ng CSA) are wrong and Thou d be d sc osed to respons b e adu u. Th s nformat on may have nf uenced (and may current y be nf uenc ng) young women's d sc osure patterns. For Wave I, compar son of these data w th the popu at on parameters obta ned from the U.S. Census Bureau nd cated that the samp e c ose y matched the demograph c attr butes of the popu at on of U.S. women Note. SCL-90 = Symptom Check List-90: SES = socioeconomic status: L N = ong interview method: CA = chi d sexua abuse: N CHD = Nationa nstitute of Chi d Heath and Human Deve opmenc USE = unwanted sexua experiences: NSA = Nationa Survey of Ado escents: NWS = Nationa Women's Study: Q DS = Questionnaire informattse sur es dE inquants sexeu s. EFTA00024191

Page 18 - EFTA00024192

276 TRAUMA, VIOLENCE, & ABUSE 20(2) examples of this usage were found in the research questions, interview guides, and surveys examined: "How and when do people decide to tell others about their early sexual experiences with adults?" (Hunter, 2011, p. 161); "Some men take many years to tell someone that they were sexually abused. Please describe why it may be difficult for men to tell about/discuss the sexual abuse" (Easton, Saltzman, & Willis, 2014, p. 462). "Participants were asked a series of open-ended questions to elicit a narrative regarding their experiences of telling..." (McElvaney, Greene, & Hogan, 2012, p. 1160). "Who was the first person you told?" (Schaeffer, Leventhal, & Anes, 2011, p. 346). There was sound consistency between studies, defining dis- closure in multifaceted ways with uniform use of categories of prompted, purposeful, withheld, accidental, direct, and indi- rect. However, defining the period of time that would delineate a disclosure as delayed varied widely across studies, wherein some studies viewed I week or I month as a delayed disclosure (i.e., Hershkowitz et al., 2007; Kogan, 2004; Schembucher, Maier, Moher-Kuo, Schnyder, & Lamdolt, 2012). Other studies simply reported average years of delay sometimes as long as from 20 to 46 years (Easton, 2013; Jonzon & Linblad, 2004; Smith et al., 2000). Second, the number of qualitative studies has increased sig- nificantly over the last 15 years. This rise is in response to a previous dearth of qualitative studies. Based on Jones's (2000) observation that disclosure factors and outcomes had been well documented through quantitative methods; in a widely read editorial, he recommended "Qualitative studies which are able to track the individual experiences of children and their percep- tion of the influences upon them which led to their disclosure of information are needed to complement ... " (p. 270). Third, although a few studies strived to obtain representative samples in quantitative investigations (Hershkowitz, Horowitz, & Lamb, 2005; Kogan, 2004; Smith et al., 2000), sampling was for the most part convenience based, relying on voluntary par- ticipation in surveys and consent-based participation in file reviews (Collings, Griffiths, & Kumalo, 2005; Priebe & Sve- din, 2008; Schembucher et al., 2012; Ungar, Barter, McConnell, Tutty, & Fairholm, 2009a). Therefore, generalizability of find- ings is understandably limited. The qualitative studies used purposive sampling as is deemed appropriate for transferability of findings to similar populations. Some of those samples con- tained unique characteristics, since they were sought through counseling centers or sexual advocacy groups. These would be considered clinical samples producing results based on disclo- sures that may have been delayed or problematic. This might presumably produce data skewed toward bathers and bring fonvard less information on disclosure facilitators. Through an in-depth, second-level analysis, this review identified five distinct themes and subthemes beyond the gen- eral trends as noted earlier. Theme 1: Disclosure is viewed as an ongoing process as opposed to a discrete event—iterative and interactive in nature. A subtheme was identified regarding disclosure as being facilitated within a dialogical and relational context is being more clearly delineated. Theme 2: Contemporary disclosure models reflect a social—ecological, person-in-environment perspective to understand the complex interplay of individual, familial, contextual, and cultural factors involved in CSA disclosure. Subthemes include new categories of disclosure and a grow- ing focus on previously missing cultural and contextual factors. Theme 3: Age and gender are strong predictors for delaying disclosure or withholding disclosure with trends showing fewer disclosures by younger children and boys. One sub- theme emerged that intrafamilial abuse/family-like relation- ship of perpetrator has a bearing on disclosure delays or withholding. Theme 4: There is a lack of a cohesive life-course perspec- tive. One subtheme includes the lack of data within the 18- to 24-year-old emerging adult population. Theme 5: Significantly more information is available on barriers than on facilitators of CSA disclosure. Subthemes of shame, self-blame, and fear are uniformly identified as disclosure deterrents. Disclosure as an ongoing process: Iterative and interactive in nature. Disclosure is now generally accepted as a complex and lifelong process, with current trends showing that CSA disclosures are too often delayed until adulthood (Collin-Vezina et al., 2015; Easton, 2013; Hunter, 2011). Knowledge building about CSA disclosure has moved in the direction of understanding this as an iterative and interactive process rather than a discrete, one- time event. Since the new millennium, disclosure is being viewed as a dynamic, rather than static, process and described "not as a single event but rather a carefully measured process" (Alaggia, 2005, p. 455). The catalyst for this view originates from Summit (I 983) who initially conceptualized CSA disclo- sures as process based, although this notion was not fully explored until several years later. Examinations of Summit's (1983) groundbreaking proposition of the CSA accommodation (CSAA) model produced varying results as to whether his five stages of secrecy, helplessness, entrapment and accommoda- tion, delayed, conflicted, and unconvincing disclosures, and retraction or recantation, hold validity (for a review, see Lon- don, Bruck, Ceci, & Shuman, 2005). However, the idea of disclosure as a process has been carried over into contemporary thinking. Recently, McElvaney, Greene, and Hogan (2012) detailed a process model of disclosure wherein they describe an interac- tion of internal factors with external motivators which they liken to a "pressure cooker" effect, preceded by a period of containment of the secret. Moreover, this and other studies strongly suggest disclosures are more likely to occur within a dialogical context—activated by discussions of abuse or pre- vention forums providing information about sexual abuse (Hershkowitz et al., 2005; Jensen, Gulbrandsen, Mossige, Reichelt, & Tjersland, 2005; Ungar et al., 2009a). The term EFTA00024192

Sponsored

Page 19 - EFTA00024193