HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_031569 - HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_031590

Document HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_031569 is an email from Jeffrey E. to Peter Thiel, dated May 19, 2014, containing a "FP Briefing non-classified" with links to articles on international affairs.

The document is an email transmitting a collection of news articles related to international politics and economics. The articles cover topics such as the future of Egypt, Saudi-Iran talks and their implications for Lebanon, India's political landscape, the Cyprus situation, and China's foreign policy in Syria. The email suggests a professional or informational relationship between the sender and recipient.

Key Highlights

- •Email from jeffrey E. ([email protected]) to Peter Thiel.

- •Subject: FP Briefing non-classified, dated May 19, 2014.

- •Contains links to articles from various sources like The National Interest, The Economist, The Christian Science Monitor, Hürriyet, and The Diplomat.

Frequently Asked Questions

Books for Further Reading

Perversion of Justice: The Jeffrey Epstein Story

Julie K. Brown

Investigative journalism that broke the Epstein case open

Filthy Rich: The Jeffrey Epstein Story

James Patterson

Bestselling account of Epstein's crimes and network

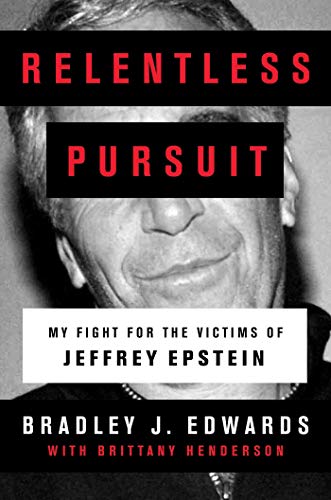

Relentless Pursuit: My Fight for the Victims of Jeffrey Epstein

Bradley J. Edwards

Victims' attorney's firsthand account

Document Information

Bates Range

HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_031569 - HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_031590

Pages

22

Source

House Oversight Committee

Document Content

Page 1 - HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_031569

From: Sent: To: Subject: jeffrey E. [[email protected]] 5/19/2014 10:37:05 AM Peter Thiel That was fun, see you in 3 weeks FP Briefing non- classified 19 May, 2014 Article 1. The National Interest Which Road Will Egypt Take? Kathryn Alexeeff Article 2. Article 3. Article 4. Article 5. Article 6. Article 7. Now Lebanon What Saudi-Iran talks could mean for Lebanon and the region Alex Rowell The Economist India's next prime minister: The Modi era begins The Christian Science Monitor An India ready to dream big Editorial Hürriyet Will it be Cyprus' vear? Yusuf Kanli The National Interest Stars Are Aligned for a Solution in Cyprus Özdil Nami The diplomat China's Instructive Syria Policy Adrien Morin HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_031569

Page 2 - HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_031570

Article 1. The National Interest Which Road Will Egypt Take? Kathryn Alexeeff May 19, 2014 -- With Abdul Fattah al-Sisi's official resignation from the military and bid for the presidency, the future of Egypt looks murky at best. While his victory is highly likely, the question remains down which path will he take Egypt? Al-Sisi's support for the anti-Morsi protesters may indicate support for the democratization of Egypt and the will of the people. On the other hand, his bid looks like a giant leap backwards for Egypt, a return to a military dictatorship. Egypt has several potential paths forward under an al-Sisi government, none of which are ideal. Unfortunately, Egypt appears to be justifying analysts' worst fears and will likely return to a Mubarak-style military autocracy under al-Sisi. The first option is a military government that enacts economic and political reforms that improve the lives of the citizenry, not just the military or the elites. This will lead to a slower evolution toward democracy. On the plus side, slower evolution under a stable government would allow structural changes to take root, fostering effective institutions and greater stability. The negative side is that evolution of this sort would be neither smooth nor straightforward. It would come in fits and spurts, punctuated by returns to oppression and violence. It would also be extremely slow, and easy for a demagogue to reverse. Unfortunately, given Egypt's current situation, option one is highly unlikely. Given the high levels of repression and violence, the only reforms the government will likely enact would involve greater centralized power in its hands. Furthermore, there are a myriad of ways for a government to pay lip service to democratization without actually decreasing its power. Another option is that Egypt becomes stuck in a proverbial time loop-repeating the revolution every year or two when the government fails to deliver on HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_031570

Page 3 - HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_031571

actual, on-the-ground improvements. This would not necessarily make Egypt worse off, but it could further weaken the economy as revenue from key industries, such as tourism, continues to decline. It would not improve conditions either, as improvements, unfortunately, take longer that the voting public generally likes. The potential upshot of this option is that, hopefully, over time, mass action would become more and more cohesive and leaders start to emerge from the morass. This would bring developed political parties into Egypt's political system and potentially, leaders from outside the military and the elite as well. This, however, will remain only a temporary option. Revolutions, or even mass action, are difficult to maintain over time. Moreover, if some improvements, particularly economic improvements, do occur, the majority of the country will acquiesce to a nondemocratic government. The best example of this is the Chinese government, which has managed economic growth without any accompanying political liberalization. Eventually, either a government will improve conditions for the average Egyptian, or it will become so repressive that mass action ceases to be a viable option. The third option is a total crackdown on any and all political movements and the return of a repressive and autocratic government. The impetus behind this path is the idea that establishing stability is the first and foremost priority of the government. If you establish stability, the rest will follow. Or, if the government is truly cynical, it simply does not care what happens as long as the ruler and his or her cronies are taken care of. Right now, it looks as though Egypt has chosen to go with option three, the return to repression under military rule. The first step for any autocracy is to get a firm grip on the political process, weeding out the opposition. This is precisely what has been occurring. Massive repression of the Muslim Brotherhood is the most obvious example of this process. While there are some legitimate security concerns regarding the Muslim Brotherhood ties to ongoing violence, banning the entire organization and labeling them all as terrorists is like using a sledgehammer on a nail-overkill and likely to create a mess. It does, however, have the benefit of getting the only meaningful political party out of the current political scene and that is a key step in political consolidation. Other examples of consolidation abound, including HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_031571

Sponsored

Page 4 - HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_031572

harsh treatment of dissents and a crackdown on journalists. While Egypt is headed down the path of autocracy, this does not suggest the futility of change or of promoting democracy in Egypt, nor, say, that the Arab Spring was a failure. Autocracy will not be a permanent fix for the factors that nourished the Arab Spring. It will work for a while, maybe even a decade, but eventually, repression will not be enough, and the demonstrations will begin again. A little liberty is a dangerous thing— especially when it bears fruit. The Arab Spring in Egypt may not have brought about democracy, but that does not mean it failed. Egypt now knows the impact mass action can have on its government. They have seen not one, but two governments fall as a direct result of protests and popular action. Egypt may be moving back toward a military dictatorship, but now the people have a taste of liberty. No matter how repressive the military establishment decides to be, the genie is out of the bottle. Kathryn Alexeeff holds a master's degree in Security Studies from Georgetown University and has worked at the Atlantic Council's South Asia Center. Article 2. Now Lebanon What Saudi-Iran talks could mean for Lebanon and the region Alex Rowell May 16, 2014 - In a potentially momentous surprise move that could herald an alleviation of political and sectarian conflict across the Middle East, Saudi Arabian Foreign Minister Prince Saud al-Faisal announced on Tuesday an invitation to his Iranian counterpart to travel to Riyadh to enter negotiations over the rival countries' "differences." HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_031572

Page 5 - HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_031573

Saudi and Iran, powerhouses of Sunni and Shiite Islam respectively, presently support opposing sides in many of the Middle East's major confrontations, and are often seen as having radically divergent and competing visions for the future of the region. Which is why, in Lebanon - a country where the two powers wield extensive influence over their respective allies - the news of a possible rapprochement has already sparked confidence that political deadlock on a number of key disputes may be resolved, perhaps even defying expectations of a presidential vacuum by ushering in a successor to President Michel Suleiman in time for the expiry of his term on 25 May. "I [now] believe we will have an elected president on the 25th," said MP Ahmad Fatfat of the Saudi-supported Future Movement. "That [Prince Faisal's] invitation was public means they already agreed on many points under the table. That means the negotiations regarding the new president have already been done." Beyond the elections, Fatfat added the talks would likely also yield wider benefits in terms of security and the economy. Earlier this week, Saudi lifted what has been described as an "unofficial ban" on its citizens traveling to Lebanon, fueling hopes of a boost to the country's struggling tourism industry. Saudi analysts concurred that the overall situation in Lebanon would likely improve in the near future. "I think in Lebanon there is already agreement [between Saudi and Iran]," said Jamal Khashoggi, veteran Saudi journalist and former advisor to then- ambassador Prince Turki al-Faisal. "The agreement in Lebanon is to contain the situation." In neighboring Syria, however, where Iranian-backed regime forces continue to suppress a Saudi-supported armed rebellion, Khashoggi expects very little to materialize from Saudi-Iranian talks. "I'm not optimistic," he told NOW. "The Saudis and Iranians are still far apart. The Iranians must relinquish their expansionism toward the Mediterranean, or we have to give up Syria. And I don't think we can afford to give up Syria. And besides, even if we decide to give up Syria, the Syrian people are not going to give up Syria." HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_031573

Page 6 - HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_031574

"So basically, the Iranians are acting like the Israelis - they want peace, and they want to keep the land." Other analysts, while conceding any progress would be slow, had somewhat more positive forecasts on the Syrian front. "[Syria] is a tough one to happen quickly, but at least if they start talking then it's a good thing," said Andrew Hammond, policy fellow at the European Council on Foreign Relations and author of The Islamic Utopia: The Illusion of Reform in Saudi Arabia. "Fundamentally, the chances of the Syrian tragedy being brought to an end, or the beginning of this disaster being brought to an end, require these two countries to come to an agreement [...] They are the keys to the Syrian conflict, so they have to start talking, even though it will take a long time." Accordingly, with little chance of the two reaching agreement on Syria in the immediate future, the talks may in fact focus on other areas of dispute, such as Iraq, where a new coalition government is being formed following parliamentary elections on 30 April. "The other issue is Iraq, now that the election is over and all the horse- trading is beginning," said Hammond. "I wonder whether that actually may have been the main impetus for this invitation." Perhaps the most significant changes resulting from Faisal's initiative in the long run, however, will pertain to Saudi itself. Having been "shocked," as Hammond put it, by the United States' decision to pursue warmer ties with Tehran last year, and initially threatening a "major shift" in its relations with Washington as a consequence, Riyadh may now be grudgingly coming to terms with the new order envisaged by President Obama. "It does suggest there is a potential for them to reassess the situation and try and move things forward, find some way of having a new relationship with the Iranians, given the fact that the Americans clearly want to move forward, and the smaller Gulf states do as well," said Hammond. HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_031574

Sponsored

Page 7 - HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_031575

Alex Rowell joined NOW in Beirut as a reporter and blogger in February 2012. A British citizen, he was raised in Dubai and studied economics in London. Article 3. The Economist India's next prime minister: The Modi era begins May 18th 2014 -- IN THE days since May 16th when Narendra Modi and his Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) stormed to victory in India's general election much commentary has wrestled with the idea of history. Most commentators seem to agree that May 2014 marks an historic moment. One reason is the scale of Mr Modi's landslide victory, which scooped up 282 seats for the BJP and thus an absolute majority in parliament. That is first time since 1984 that any party has won a majority for itself. It is also the first time ever that a party other than Congress has done so. Conversely, the defeat for Congress is far worse than anything in its long history of dominating Indian politics: it won fewer than a sixth the seats of its rival, getting just 44. In much of north India, the political heartland, Congress was wiped out. Some correctly ask if its eventual recovery (assuming that will happen one day) would require being rid of the Nehru- Gandhi dynasty that has been at its heart for so long. Yet the size of Mr Modi's victory, and Congress's defeat, tells only part of the dramatic story. The immense dissatisfaction with Congress was undeniable. Voters were unhappy with high inflation, slowing growth, weak leadership, corruption and much more. Such voter grumpiness, usually summed up as "anti-incumbency" ", is all but inevitable for a party that had been in power for a decade. Yet more has happened here. Take, for example, the utter defeat of the Bahujan Samaj Party of Mayawati, the Dalit leader in Uttar Pradesh. She was not an incumbent and her party HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_031575

Page 8 - HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_031576

managed to collect some 20% of the votes cast in the state. Indeed, after the BJP and Congress, it got the most votes nationally of any party in the election. Yet it failed to win a single constituency. By contrast the BJP not only collected a huge tally of votes but also turned those efficiently into seats. With 31% of the national vote-share, they captured nearly 52% of the seats in parliament. That suggests an important shift in Indian politics. The BJP did extraordinarily well because it approached the election in a far more professional, strategic and efficient way than its rivals. The methods it employed were modern, and the skill at which Mr Modi and his fellow leaders conducted their campaigns rivalled the sort of performances put in by American presidential contenders (and with similar quantities of money to spend). Rahul Gandhi of Congress, in the end, proved to be a hopeless amateur, poorly advised without even decent media-management skills or the ability to present a strong campaign message. Many regional figures proved similarly out of date in their campaigning. The BJP's roadshows and rallies, the door-knocking by volunteers, the influence on India's press and television channels, the ability to set the agenda of discussion, all went to making the election a remarkably one-sided affair. The chief minister of Bihar, Nitish Kumar, tendered his resignation on May 17th, after his party was flattened by the BJP in the state. (Assam's chief minister, from Congress, has also offered to quit.) That was not because of anti- incumbency-voters in Bihar are happy with the work Mr Kumar has been doing— but because the BJP's campaign was vastly superior. Mr Modi in his first speeches after his victory has sounded magnanimous and made the right noises about running the country for all, bringing everyone along. He also mentioned, only partly accurately, that the BJP's success transcended caste politics and religious appeals. If that were entirely true, it would be another reason to call this election result historic. In fact the BJP did make some use of caste and religion, as when Mr Modi played up his "other backward classes" background while campaigning in Uttar Pradesh, or when he criticized Bangladeshi (read: Muslim) infiltrators in Assam and West Bengal. It is troubling, too, that the new parliament will have the fewest Muslim members of any since 1952, while HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_031576

Page 9 - HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_031577

the ruling BJP has not a single Muslim MP among its cohort of 282; Muslims are reckoned to comprise at least 14% of the Indian population. But largely Mr Modi told the truth: the BJP's manifesto and Mr Modi's speeches emphasised economic and development matters. The victory he achieved is more the result of his talk of strong government and improvements to the material lives of voters than anything else. That is encouraging. It suggests that he will now seek to govern in a way that encourages economic growth, job creation and better infrastructure, along with further reductions in poverty and inflation. Mr Modi has been dropping strong hints that he hopes to remain in power not only for the current five-year term, but to win re-election and reshape India's economy and political landscape. In other words, he is considering his long-term prospects by keeping in mind the rise of a powerful new constituency that will only gather more influence as the years pass: the young, urban, educated and impatient set of voters who aspire for material gains to their lives. We argued before that such voters, for whom there is only "one God, that is GDP", , will increasingly decide the outcome of Indian elections. Mr Modi and the BJP look set to corner their support. What comes next? On May 20th the BJP will meet, apparently to elect Mr Modi formally as their leader. That, apparently, is a precursor to the formation of a government which is going to include the immediate allies of the party that make up the National Democratic Alliance. It could, too, be made from of a wider coalition, since the BJP—if it is to push through legislative changes quickly-will need additional help from other parties that control powerful states, and to win more support in the upper house of parliament. Unease persists about the role of the Hindu-nationalist right, whose footsoldiers undoubtedly helped a great deal in getting BJP candidates elected. With Mr Modi having been an activist member in the right-wing Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS) since he was a boy, some on the right have expectations that he will pursue an agenda of Hindutva (for example getting a temple erected in Ayodhya, or changing the constitutional status of Muslim-majority Kashmir). Others look for evidence that nationalism of a protectionist variety will have a strong HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_031577

Sponsored

Page 10 - HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_031578

influence on Mr Modi's policies. For example over the weekend BJP spokesmen have been saying that the party still intends to reverse an existing policy that would allow foreign investors to open supermarkets in larger cities, and even then only under limited circumstances. Mr Modi would be wiser to downplay the influence of both sorts of nationalists. To sustain confidence that he can get the economy growing faster will require pulling off some difficult feats, not least attracting more foreign capital into a host of industries which could include insurance, banking, defence and many parts of infrastructure. He needs to send a clear message, as he picks ministers and begins to offer policy, that India aspires to become strong on the back of economic growth, more international trade, deeper global engagement—and not by promoting nationalist tendencies at home. He has a decent record of reaching out to other countries, notably Japan, in his time as chief minister of Gujarat. Since his victory on May 16th he has fielded calls from Barack Obama, David Cameron and a host of other global well-wishers eager to engage India internationally. Mr Obama for example made clear that India's prime minister would be welcome to visit the United States. The Americans in particular want a decisive break from an earlier period, when interaction with Mr Modi concerned his record in handling communal violence in his state in 2002. Mr Modi in other words, by winning so emphatically on May 16th, appears both to have made history and escaped it. That is no mean feat at all. Article 4. The Christian Science Monitor An India ready to dream big Editorial May 18, 2014--Years before Narendra Modi won this month's election that now allows him to become India's next leader, the former tea-stall HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_031578

Page 11 - HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_031579

worker asked this question on behalf of the world's second most-populous nation: "It is often said that India does not dream big and that is the root cause of all our problems. Why can't we dream like China, Europe or America?" Note how Mr. Modi compares India to other continental powers. This reveals just how much today's 1.25 billion Indians, who are digitally hitched to the global flow of ideas, have adopted new views of their capacity for progress - not only for India but for themselves. During his campaign, Modi tapped into this rising aspiration for India to emulate the best in other countries. One in eight voters went to the polls for the first time, a sign of the fact that two-thirds of the population is under 35. He and his Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) promised economic growth, clean governance, and decisive leadership, all of which Modi delivered as chief minister of Gujarat state - although sometimes too harshly or divisively. His record and his campaign promises really reflect an India ready to join the global community. Voter turnout was a record 66 percent. And the electoral results cut across the old divides of caste, rural vs urban, old vs. young, poor vs. middle-class. On those measures alone, India has surpassed China, which is not even allowed to have elections, and the political disunity in Europe and America. The BJP's election sweep was achieved in part out of public frustration with the long-ruling Congress party. Its corrupt, paternalistic, and dynastic style no longer fits an India of smart phones and social mobility. More than two-thirds of Indians are dissatisfied with their country's direction, according to a Pew poll. In throwing off the past, voters have allowed the BJP to rule with a clear majority in the lower house of parliament. Such a feat was achieved only once before, in 1984, after the assassination of Indira Gandhi boosted the Congress party in an election. As prime minister, Modi must not forget he is riding an awakening of Indian expectations as much as leading them. His checkered past as a Hindu nationalist, and in sometimes treating India's Muslims as less than citizens, cannot color his leadership in a constitutional democracy. HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_031579

Page 12 - HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_031580

Religion, including Hinduism and Islam, can help Indians define their individual identity. But in a country of such size and diversity, one that is home to a third of the world's poor, only secular rule can ensure the unity needed to fulfill people's collective hopes. "India has won," Modi tweeted after his victory. This apparent humility may serve him well in preventing an overreach of his powers. India does not need big-man style rule now that a historic election has shown Indians are ready to dream big. Article 5. Hürriyet Will it be Cyprus' year? Yusuf Kanli 19 May 2014 -- The highlight of the one-day trip to North Cyprus by Foreign Minister Ahmet Davutoglu might best be his bold declaration that time has come to end the 50-year-old Cyprus problem. Can there be relevance between the age and the time for the resolution of a problem? Obviously not, but a minister expressing conviction that time has come to end a problem carries incredible importance and naturally boosts expectations to that end Is it really the high time, best opportunity, right moment, last chance or whatever for a Cyprus deal? All through the past many decades, somehow many prominent and otherwise effective personalities, including not only Davutoglu and people of his caliber, but many premiers, presidents and at least every American leader since George Bush Sr. have declared many of the past years as the "Cyprus year" but that Cyprus year never came... Will it come this time? Sure... the Cyprus problem could easily be resolved if the two sides on the island ever develop sufficient political will; prepare their respective societies to be receptive to a painful compromise and international actors stop paying lip service to the idea of a resolution, but instead genuinely support a resolution. HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_031580

Sponsored

Page 13 - HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_031581

Do the two sides on Cyprus have political will? Does Turkey want a settlement? Is Greece prepared for a deal that might trigger a larger deal with Turkey over the Aegean and Thrace issues? Of these questions only one element is affirmative; Turkish Cypriots want a settlement. In 2004, they not only demonstrated simultaneous referenda, but repeated polls have shown since then that the pro-settlement resolve of Turkish Cypriots is over 65 percent. Greek Cypriots? Polls show a decreasing 41 percent are receptive to the idea of resolution, less than 30 want federation. Officially, both Greece and Turkey support a compromise deal on Cyprus. How sincere are they? Last time, in 2004, despite all of the pledges made before, Greece eventually could not support a plan for resolution. Will it support a compromise deal this time? Let us hope it will. Turkey will support any deal supported by Turkish Cypriots, provided it somehow maintains a presence on the island. Why should it not, after all, if Britain, a country far away, has two sovereign bases just because it was the previous colonial power? Was it not Turkey that leased the island to Greece? International actors all keep on vowing to support a deal on Cyprus. Why would the British want a settlement knowing that despite the recent agreement it signed in haste with the Greek Cypriots, British bases on Cyprus will be the next and joint target for all Cypriots if ever they resolve their bilateral quagmire? Russians would not want a resolution either. Why should they? To upset their peculiar position as the major energy supplier of Europe, (particularly) to Germany? Or to render life even more difficult to the Russian population and collaborators engaged in bleaching business? Why would Americans support a compromise deal if they benefit more from the British bases on the divided Cyprus? The upcoming visit of American Vice President Joe Biden this week and the anticipated visit to the island within weeks by Secretary of State John Kerry of course demonstrate an interest in the Cyprus problem. A visit by a U.S. vice president - the first in 52 years - of course will be meaningful. Plans to ease European energy dependency on Russia might play a role for an accelerated demand for a Cyprus deal push. Don't the Americans know HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_031581

Page 14 - HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_031582

better than anyone else a Cyprus peace requires engagement in goodwill and determination by both sides and of course at least Turkey, if not Turkey and Greece together? Why would Greek Cypriots want a resolution as long as they enjoy alone the "sole legitimate government" of Cyprus and the Turkish Cypriot part of the island is considered only as "areas not under the government's control?" Yes, Davutoglu may wish to see accelerated peace talks and a commitment from Nikos Anastasiades to work for a deal "as soon as possible." In view of the latest European Court of Human Rights and these plain realities, can that be possible anytime soon? Article 6. The National Interest Stars Are Aligned for a Solution in Cyprus Özdil Nami May 19, 2014 -- The Cyprus problem is at a critical juncture as there exists a unique opportunity for its solution. If this opportunity is utilized, a united Cyprus will be the keystone of a wider area of cooperation and stability in the Eastern Mediterranean and beyond. A glance at the issues that are affected by or directly resulted from the prolongation of the problem clearly highlights the need for an early settlement in Cyprus. The 50th Year on the UN Agenda The Cyprus problem has been on the agenda of the United Nations for half-a-century. For decades, it has consumed considerable diplomatic and political effort, domestic and international alike, but to no avail. As such, it has gained a reputation as an intractable and inexorable problem that eluded an ultimate settlement. The island of Cyprus, nearly half the size of the state of Connecticut, has subsequently become synonymous with conflict, despite its nostalgic narrative as a haven of peaceful coexistence. Since the drawing of the Green Line in 1963, Nicosia, the Janus-faced HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_031582

Page 15 - HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_031583

capital of both North and South Cyprus, remains today as the last divided city in Europe and the only divided capital in the world. However, the Cyprus problem has to change face and move on from this conundrum characterized by a relentlessly enduring state of conflict to an inspirational success story of peace. Time is ripe for such a change, especially in view of current dynamics that are molding together both on the island and in the region. Missed Opportunities April 24, 2014 marked the 10th anniversary of the referenda held on the UN Comprehensive Settlement Plan (the Annan Plan) on both sides of the island. This was the first time in the history of Cyprus negotiations that a comprehensive settlement document, comprising 9,000 pages, was put to separate simultaneous referenda. The Turkish Cypriots accepted the plan with an overwhelming majority (65 percent), despite the great sacrifices it entailed for them. They did not only vote in favour of a solution, but also for moving beyond the traumatic past and building a common future within the EU through a new partnership with Greek Cypriots. Unfortunately, the Plan failed due to the resounding "no' vote (76 percent) of the Greek Cypriots. Nevertheless, the Turkish Cypriot aspiration for a solution has prevailed even in the face of deep frustration ensuing the Greek Cypriot rejection of the Annan Plan and the continued isolation imposed on Turkish Cypriots in all aspects of life. The fact that they have been left out in the cold, while the Greek Cypriot side has unilaterally become a member of the EU, did not change the Turkish Cypriots' resolve for settlement. Yet, it further complicated the prospects of reconciliation on the island. Thriving Opportunities from Within Against this background, the Turkish Cypriot side has intensified its endeavors to overcome this crisis of confidence and engaged sincerely with the Greek Cypriot side for the preparation of the ground for a new dialogue. Subsequently, the two sides were able to initiate a series of agreements in early 2008, which paved the way for the resumption of full- fledged negotiations after a four-year stalemate. Since then, intermittent HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_031583

Sponsored

Page 16 - HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_031584

negotiations have been underway, with significant progress attained on the majority of the chapters of the Cyprus problem as a result of the intensive efforts put forward by the two sides in reaching convergences. Furthermore, with the recent agreement on the Joint Declaration of February 11, 2014, an important milestone in the negotiations has been reached, which clearly provides for the broad outline of a solution and the main principles upon which the new partnership will be established. Hence, the announcement of the Joint Declaration triggered a very positive atmosphere that was further fostered by the support of a wide spectrum of actors on both sides as well as the extensive espousal received by the international community. The Far-Reaching Consequences of the Problem In light of this promising political climate on the island, combined with the existence of some external factors that are currently at play, there is an historic opportunity that should not be missed in bringing the long- overdue Cyprus problem to a closure. The recent developments in our region strongly signal a pressing need in this direction. It is beyond doubt that the Cyprus problem holds back the potential of cooperation in a broader context. Since its conception, the relations between Turkey and Greece have been negatively affected by it. A full-scale rapprochement between the two countries has been held hostage to the chronic status quo on the island. In the course of time, this has been exploited as an excuse to oppose Turkey's bid for EU membership through the blocking of some chapters in her accession talks. EU-NATO strategic cooperation has also been hampered in a similar fashion due to the non-existence of diplomatic relations between South Cyprus and Turkey. As a NATO member, Turkey has proven to be an indispensable strategic partner of the Transatlantic cooperation since the inception of the Cold War. Although a NATO Council decision in late 2002 enabled the participation of the non-EU members of NATO in the European Security and Defense Policy (ESDP), the Greek Cypriot side has been blocking Turkey's involvement both in the ESDP and her prospective membership in the European Defense Agency (EDA). As a result, no meaningful dialogue can practically be established between the EU and NATO, creating a situation whereby the HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_031584

Page 17 - HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_031585

Cyprus problem is literally obstructing the deepening of the EU-NATO strategic relations. The current crisis in Ukraine clearly highlighted, once again, the need for closer cooperation between the two institutions. External Dynamics Necessitating a Settlement The crisis in Ukraine also brings forward the necessity of alternative energy supplies en route to Europe. Recently, the island of Cyprus has driven considerable attention as a result of the newly found energy reserves in the Eastern Mediterranean. Common sense dictates that Turkish Cypriots and Greek Cypriots, together with neighboring countries, adopt a win-win approach and share the benefits of the natural resources of the region on an equitable basis. Such cooperation and the resulting interdependency could only bring much needed stability and prosperity to the region and help restore the ties between Turkey and Israel. The Promise of a Solution Cyprus lies at a strategic crossroads between the East and the West. However, as all these developments indicate, the island's full potential can only be utilized with the solution of the Cyprus problem. A solution will not only provide for peace on the island, but will also prompt a wave of cooperation in its wider region. Therefore, all relevant actors, including the two sides on the island, should act in a spirit of good-will and compromise in bringing an end to this half-century-old problem. The Turkish Cypriot side is ready to do its utmost in this regard, with a view to realizing the island's destiny to become a hub for peace and stability rather than a source of conflict and tension. Özdil Nami is the Minister of Foreign Affairs for the Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus. Article 7. The diplomat China's Instructive Syria Policy HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_031585

Page 18 - HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_031586

Adrien Morin May 18, 2014 -- The crisis in Syria erupted early in 2011 as part of the Arab Spring and worsened as the year went on. A first draft resolution to intervene in Syria was proposed by France, Germany, Portugal and the U.K., on October 4. This proposal was vetoed by Russia and China, marking the start of a long diplomatic impasse with Moscow and Beijing on one side and the Western powers on the other. China and Russia would later veto two more draft UN resolutions. Three years after the clashes in Syria began, and with the civil war now being supplanted in media headlines, it is worth reviewing Chinese policy. Has Beijing purposefully been more assertive toward Western powers, and the U.S. in particular? Western Concerns Chinese foreign policy worries the West on a number of fronts. One concern is the formation of a "united front" of China and Russia, to oppose Western goals. Certainly, China and Russia have together vetoed draft resolutions supported by the three other permanent members of the Security Council. The world has meanwhile witnessed China's impressive rise in recent decades as well as Russia's attempts to return to Great Power status. Perhaps an anti-Western alliance of those two actors could indeed challenge the U.S. and its allies. In the meantime, the West finds itself frustrated by Chinese foreign policy pragmatism, or as the critics would have it, the absence of values. This is de facto incompatible with Western moral ideals, which invoke human rights or other ethical arguments. Chinese realpolitik is seen as amoral, if not immoral. Chinese policy is also not up for domestic debate - a lack of transparency and little civic engagement make sure of that. Those who fear that Chinese foreign policy is driven by the intent of challenging (and eventually supplanting) the West would view Beijing's support for the Syrian regime as ideological. This concern rises as China becomes more popular in the Middle East. Mostafa Kamel, a member of the Egyptian Foreign Ministry, "expressed admiration for China's position and proposition on the Syrian issue and said that Egypt is willing to strengthen communications and HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_031586

Sponsored

Page 19 - HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_031587

coordination with China on the issue." Could the influence of Western powers in the region be weakened, for the benefit of China? All these concerns come back to one issue: China's new role within the international community. As a new - and still growing - power, some observers fear that China may soon have the ability to challenge and threaten the Western liberal model that has dominated international organizations since the end of the Cold War. The Reality These concerns are misplaced. First, the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) has a high level of suspicion toward Western proposals at the international level and within the executive organs of the United Nations in particular. China seems to view the UN as a potential tool to oppose what it considers Western interventionist policies around the world, and it is clear that the Chinese government was greatly disappointed when the United States and its allies acted on their own to impose, by force, a regime change in Iraq in 2003. The frustration was even greater during the Libyan crisis that ended with the overthrow and execution of former leader Muammar Gaddafi. Indeed, from Beijing's perspective, resolution 1973 of the United Nations seeking to impose a no-fly zone in Libya did not give any foreign power the right to intervene militarily on Libyan territory and against the Libyan regime. Beijing learned a lesson. The second element may be more important: Beijing's stance on the Syrian crisis is consistent with China's long-term foreign policy and its fundamental principles. The basis of Chinese foreign policy is articulated in the Five Principles of Peaceful Coexistence, enunciated by Zhou Enlai in 1954: 1) mutual respect for sovereignty and territorial integrity; 2) mutual non-aggression; 3) non- interference in each other's internal affairs; 4) equality and mutual benefit; and 5) peaceful coexistence in developing diplomatic relations and economic and cultural exchanges with other countries. Since the opening of the country under Deng Xiaoping in 1978, Chinese foreign policy can be more generally characterized as pragmatic. Pragmatism and the five principles are the key to understanding China's response to the Syrian crisis and indeed its general approach to foreign relations. This model excludes moral or ethical arguments from the HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_031587

Page 20 - HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_031588

practice of foreign policy, and as such is antithetical to Western ideals, which raises questions, misunderstandings, and fears among the Western powers as China emerges a major world power. The notion of peaceful development is also important, and is central to Xi Jinping's administration. This concept means that China seeks peaceful relations with other members of the international community to establish fruitful economic relations that will serve Chinese development goals. To achieve this goal, China needs a stable environment. The concept of peaceful development means, according to Xi Jinping, that "China will never seek hegemony or expansion." Although Western powers may not approve of the "Chinese Model," it does explain Chinese policy on the Syrian crisis. It is also worth noting the influence of China's domestic situation on Chinese policy in Syria. Beijing cannot legitimize any insurrection abroad, as it has to deal domestically with separatist issues (such as in Tibet, Xinjiang, or Inner Mongolia.). To show that domestic considerations can logically obliterate considerations of human rights, George Abu Ahmad, taking domestic policies of Iran, Russia or China as an example, explains that "the exceptional decision to attack the population is, therefore, not only a sovereign right of the twentieth-century state, but the paramount right that guarantees a state's integrity." This perspective helps us to understand the way in which China may have internalized the causes of the Syrian crisis in the context of its own domestic separatist issues and thus cannot provide any legitimacy to an insurrection abroad. A final point to make is China's inability and unwillingness to take on a "superpower" role within the international community. China has no experience being a political leader on the international stage, and as a result has mostly abstained in the Security Council on any draft resolution that did not directly affect its own domestic situation. Nor does it like to take any strong stances that could lead to diplomatic clashes with a major power, especially the U.S. It seems improbable, given the record of Chinese positions in the UN, that China would have opposed the Western resolutions on Syria without the support of Russia. HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_031588

Page 21 - HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_031589

The South China Sea, the Senkaku/Diaoyu, and the ADIZ Some may argue that China is clearly adopting a more assertive policy in East Asia - using the South China Sea, the Senkaku/Diaoyu islands dispute, or the Air Defense Identification Zone as examples. However, there is a difference, and this has to do with the "sphere of influence" of China and, more specifically, with the sovereignty and integrity of Chinese national territory (as Beijing defines it). For the CCP, the Syrian crisis is a "pure" foreign policy issue, as the Chinese government has no territorial claim in Syria or in the Middle East in general. On the other hand, Beijing has always considered the South China Sea and the Senkaku/Diaoyu islands as part of its sphere of influence and by vigorously defending its claims on those territorial disputes, the CCP purports to do nothing but protect its territorial integrity. It's arguable that this concern with territory has been the very first priority of China throughout its history. The debate over the East China Sea ADIZ, which China established in November, can also be related to the territorial integrity of the Middle Kingdom. However, Western criticisms should be balanced against the knowledge that the ADIZ is an American invention (1950), which South Korea (1951) and Japan (1969) adopted long before China did. At any rate, the South China Sea, the Senkaku/Diaoyu islands, and the ADIZ issues are domestic issues for the CCP, rather than "pure" foreign policy matters. This article doesn't seek to take a normative position. Rather, the point is that in the Syrian crisis China has followed a consistent foreign policy, in line with its principles and traditions. The outcome of this policy may not satisfy many Western actors, but that is not enough to accuse China of following a more assertive foreign policy toward Western powers and the U.S. in particular. Of course, the new status of China in the international community allows it to make its voice heard, instead of the silence that may have prevailed before its economic arrival. But the considerations of the CCP as it formulates its foreign policy have remained the same since the creation of the PRC. In the future, China is likely to be more capable of achieving its goals in its "domestic" Northeast Asian claims, but there HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_031589

Sponsored

Page 22 - HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_031590

is no evidence showing that the CCP is purposefully becoming more assertive in its foreign policy towards the West. Napoleon said two-hundred years ago that, when China wakes "she will shake the world." It may not be time to start shaking yet. Adrien Morin is a postgraduate student of International Affairs at Peking University. please note The information contained in this communication is confidential, may be attorney-client privileged, may constitute inside information, and is intended only for the use of the addressee. It is the property of JEE Unauthorized use, disclosure or copying of this communication or any part thereof is strictly prohibited and may be unlawful. If you have received this communication in error, please notify us immediately by return e-mail or by e-mail to [email protected], and destroy this communication and all copies thereof, including all attachments. copyright -all rights reserved HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_031590

Entities Mentioned

Adnan Khashoggi

PERSON

Saudi Arabian businessman (1935-2017)

AM

Adrien Morin

PERSON

AF

Ahmad Fatfat

PERSON

Lebanese politician

Ahmet Davutoglu

PERSON

Turkish politician (born 1959)

Al-Sisi

PERSON

Alex Rowell

PERSON

Andrew Hammond

PERSON

Canadian ice hockey goaltender

AN

anti-Morsi

PERSON

Barack Obama

PERSON • 2 mentions

President of the United States from 2009 to 2017

David Cameron

PERSON • 2 mentions

British politician (born 1966)

Davutoglu

PERSON

Turkish politician (born 1959)

Deng Xiaoping

PERSON • 2 mentions

Chinese politician and paramount leader from 1978 to 1989

FA

Fatfat

PERSON

Lebanese politician

George Abu Ahmad

PERSON

George H.W. Bush

PERSON • 2 mentions

President of the United States from 1989 to 1993 (1924–2018)

George W. Bush

PERSON • 2 mentions

President of the United States from 2001 to 2009

Hammond

PERSON

City in Lake County, Indiana, United States

Hosni Mubarak

PERSON

President of Egypt from 1981 to 2011

Indira Gandhi

PERSON

Prime Minister of India (1966–1977, 1980–1984)

Jamal Khashoggi

PERSON • 2 mentions

Saudi journalist (1958–2018)

Jeffrey Epstein

PERSON

American sex offender and financier (1953–2019)

Joe Biden

PERSON • 2 mentions

46th President of the United States (2021–2025)

John Kerry

PERSON • 2 mentions

American politician and diplomat (born 1943)

KA

Kathryn Alexeeff

PERSON

Kofi Annan

PERSON

7th Secretary-General of the United Nations (1938-2018)

Kumar

PERSON

Michel Suleiman

PERSON

12th President of Lebanon

Mostafa Kamel

PERSON

Egyptian professor and diplomat

Muammar Gaddafi

PERSON

Leader of Libya from 1969 to 2011

Napoleon

PERSON

Narendra Modi

PERSON

Prime Minister of India since 2014

Nicosia

PERSON

Capital of Cyprus

Nikos Anastasiades

PERSON

Cypriot politician, 7th President of the Republic of Cyprus (2013–2023)

Nitish Kumar

PERSON

Indian politician and Current Chief Minister of Bihar

Özdil Nami

PERSON

Turkish-Cypriot politician (born 1967)

Peter Thiel

PERSON • 2 mentions

German-American entrepreneur and venture capitalist (born 1967)

Prince Saud al-Faisal

PERSON

Rahul Gandhi

PERSON

Indian politician (born 1970)

Turki al-Faisal

PERSON

Saudi politician

Xi Jinping

PERSON • 2 mentions

General Secretary of the Chinese Communist Party since 2012

Yusuf Kanli

PERSON

Zhou Enlai

PERSON

Asia Center

ORGANIZATION

Bharatiya Janata Party

ORGANIZATION

Right-wing political party in India

Christian Science Monitor

ORGANIZATION

American nonprofit newspaper (1908-)

Councils

ORGANIZATION

EU-NATO

ORGANIZATION

European Court of Human Rights

ORGANIZATION

Faisal

ORGANIZATION

Future Movement

ORGANIZATION

Georgetown University

ORGANIZATION

Private university in Washington, D.C., United States

Hindutva

ORGANIZATION

Hürriyet

ORGANIZATION

International Affairs

ORGANIZATION

Academic journal

Parliament

ORGANIZATION

American funk band most prominent during the 1970s

Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh

ORGANIZATION

Scout

ORGANIZATION

the Atlantic Council

ORGANIZATION

the Chinese Communist Party

ORGANIZATION

the European Council on Foreign Relations’

ORGANIZATION

the Muslim Brotherhood

ORGANIZATION

The National Interest

ORGANIZATION

the U.N. Security Council

ORGANIZATION

Transatlantic

ORGANIZATION

Aegean

LOCATION

Assam

LOCATION

Indian state

Ayodhya

LOCATION

City in Uttar Pradesh, India

Beirut

LOCATION

Capital and largest city of Lebanon

Bihar

LOCATION

State in eastern India

Cyprus

LOCATION

Mediterranean island country in West Asia

East Asia

LOCATION

Eastern region of Asia

Gujarat

LOCATION

State of India

Inner Mongolia

LOCATION

Autonomous region of China

Kashmir

LOCATION

Disputed territory between China, India and Pakistan

Lebanon

LOCATION

Country in West Asia

Mediterranean

LOCATION

Middle East

LOCATION

Geopolitical region encompassing Egypt and most of Western Asia, including Iran

North

LOCATION

1994 comedy film by Rob Reiner

North Cyprus

LOCATION

De facto state on the island of Cyprus

Norther

LOCATION

Finnish melodic death metal band

Riyadh

LOCATION

Capital and largest city of Saudi Arabia

Senkaku

LOCATION

Group of islands in East Asia

Senkaku/Diaoyu islands

LOCATION

Group of islands in East Asia

South Cyprus

LOCATION

Tehran

LOCATION

Capital city of Iran

the Air Defense Identification Zone

LOCATION

the Eastern Mediterranean

LOCATION

the Middle Kingdom

LOCATION

the Senkaku/Diaoyu

LOCATION

the South China Sea

LOCATION • 2 mentions

Thrace

LOCATION

Geographical and historical region in Southeast Europe

Tibet

LOCATION

Plateau region in west China

United States

LOCATION

Country located primarily in North America

Uttar Pradesh

LOCATION

State in northern India

West Bengal

LOCATION

Indian state

Xinjiang

LOCATION

Autonomous region in China

Statistics

Pages:22

Entities:96

Avg. OCR:97.7%

Sponsored