HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_021120 - HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_021144

Document HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_021120 is a record from the House Oversight Committee that previews the contents of Michael Wolff's book 'Siege: Trump Under Fire'. The document lists the book's chapters and key figures involved during Donald Trump's second year in office.

This document, consisting of 25 pages, is from the House Oversight Committee and outlines the contents of Michael Wolff's book, 'Siege: Trump Under Fire,' which covers Donald Trump's second year as president. It includes a table of contents, an author's note, and an index. The document highlights the organizational chaos and drama within the White House, as well as the various investigations and controversies surrounding Trump's administration.

Key Highlights

- •The document is a record from the House Oversight Committee.

- •The document previews Michael Wolff's book 'Siege: Trump Under Fire,' which covers Trump's second year in office.

- •Key figures mentioned include Donald Trump, Steve Bannon, and Robert Mueller.

Frequently Asked Questions

Document Information

Bates Range

HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_021120 - HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_021144

Pages

25

Source

House Oversight Committee

Date

May 28, 2019

Original Filename

doc04312820190528150758.pdf

File Size

7.68 MB

Document Content

Page 1 - HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_021120

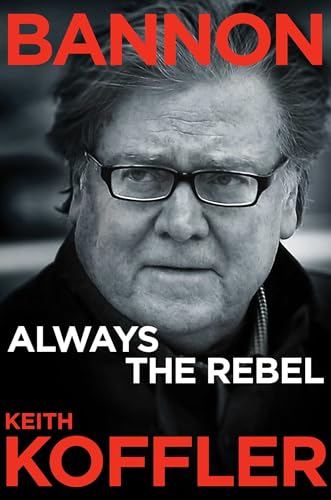

SIEGE Trump Under Fire MICHAEL WOLFF HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_021120

Page 2 - HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_021121

Contents AUTHOR’S NOTE XI 1. BULLSEYE 1 2. THE DO-OVER 21 3. LAWYERS 38 4. HOME ALONE 50 5. ROBERT MUELLER 60 6. MICHAEL COHEN 75 7. THE WOMEN 88 8. MICHAEL FLYNN 99 9. MIDTERMS 113 10. KUSHNER 125 11. HANNITY 143 12. TRUMP ABROAD 156 13. TRUMP AND PUTIN 169 HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_021121

Page 3 - HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_021122

CONTENTS 14.100 DAYS 185 15. MANAFORT 196 16. PECKER, COHEN, WEISSELBERG 209 17. MCCAIN, WOODWARD, ANONYMOUS 223 18. KAVANAUGH 234 19. KHASHOGGI 246 20. OCTOBER SURPRISES 257 21. NOVEMBER 6 268 22. SHUTDOWN 282 23. THE WALL 295 EPILOGUE: THE REPORT 309 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS 317 INDEX 319 Author’s Note Shortly after Donald Trump’s inauguration as the forty-fifth president of the United States, I was allowed into the West Wing as a sideline observer. My book Fire and Fury was the resulting account of the organizational chaos and constant drama—more psychodrama than political drama—of Trump’s first seven months in office. Here was a volatile and uncertain president, releasing, almost on a daily basis, his strange furies on the world, and, at the same time, on his own staff. This first phase of the most abnor- mal White House in American history ended in August 2017, with the departure of chief strategist Stephen K. Bannon and the appointment of retired general John Kelly as chief of staff. This new account begins in February 2018 at the outset of Trumps second year in office, with the situation now profoundly altered. The pres- ident’s capricious furies have been met by an increasingly organized and methodical institutional response. The wheels of justice are inexorably turning against him. In many ways, his own government, even his own White House, has begun to turn on him. Virtually every power center left of the far-right wing has deemed him unfit. Even some among his own base find him undependable, hopelessly distracted, and in over his head. Never before has a president been under such concerted attack with such a limited capacity to defend himself. His enemies surround him, dedicated to bringing him down. HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_021122

Sponsored

Page 4 - HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_021123

XII AUTHOR’S NOTE 4 4% I am joined in my train-wreck fascination with Trump—that certain knowledge that in the end he will destroy himself—by, I believe, almost everyone who has encountered him since he was elected president. To have worked anywhere near him is to be confronted with the most extreme and disorienting behavior possible. That is hardly an overstate- ment. Not only is Trump not like other presidents, he is not like anyone most of us have ever known. Hence, everyone who has been close to him feels compelled to try to explain him and to dine out on his head-smacking peculiarities. It is yet one more of his handicaps: all the people around him, however much they are bound by promises of confidentiality or nondisclosure agreements or even friendship, cannot stop talking about their experience with him. In this sense, he is more exposed than any president in history. Many of the people in the White House who helped me during the writing of Fire and Fury are now outside of the administration, yet they are as engaged as ever by the Trump saga. I am grateful to be part of this sub- stantial network. Many of Trump’s pre-White House cronies continue to both listen to him and support him; at the same time, as an expression both of their concern and of their incredulity, they report among one another, and to others as well, on his temper, mood, and impulses. In general, I have found that the closer people are to him, the more alarmed they have found themselves at various points about his mental state. They all spec- ulate about how this will end—badly for him, they almost all conclude. Indeed, Trump is probably a much better subject for writers interested in human capacities and failings than for most of the reporters and writers who regularly cover Washington and who are primarily interested in the pursuit of success and power. My primary goal in Siege is to create a readable and intuitive narrative— that is its nature. Another goal is to write the near equivalent of a real-time history of this extraordinary moment, since understanding it well after the fact might be too late. A final goal is pure portraiture: Donald Trump as an extreme, almost hallucinatory, and certainly cautionary, Amer- ican character. To accomplish this, to gain the perspective and to find AUTHOR’S NOTE XIII the voices necessary to tell the larger story, I provided anonymity to any source who requested it. In cases where I have been told—on the prom- ise of no attribution—about an unreported event or private conversation or remark, I have made every effort to confirm it with other sources or documents. In some cases, I have witnessed the events or conversations described herein. With regard to the Mueller investigation, the narrative I provide is based on internal documents given to me by sources close to the Office of the Special Counsel. Dealing with sources in the Trump White House has continued to offer its own set of unique issues. A basic requirement of working there is, surely, the willingness to infinitely rationalize or delegitimize the truth, and, when necessary, to outright lie. In fact, I believe this has caused some of the same people who have undermined the public trust to become pri- vate truth-tellers. This is their devil’s bargain. But for the writer, interview- ing such Janus-faced sources creates a dilemma, for it requires depending on people who lie to also tell the truth—and who might later disavow the truth they have told. Indeed, the extraordinary nature of much of what has happened in the Trump White House is often baldly denied by its spokespeople, as well as by the president himself. Yet in each successive account of this administration, the level of its preposterousness—even as that bar has been consistently raised—has almost invariably been con- firmed. In an atmosphere that promotes, and frequently demands, hyperbole, tone itself becomes a key part of accuracy. For instance, most crucially, the president, by a wide range of the people in close contact with him, is often described in maximal terms of mental instability. “I have never met anyone crazier than Donald Trump” is the wording of one staff member who has spent almost countless hours with the president. Something like this has been expressed to me bya dozen others with firsthand experience. How do you translate that into a responsible evaluation of this singular White House? My strategy is to try to show and not tell, to describe the broadest context, to communicate the experience, to make it real enough for a reader to evaluate for him- or herself where Donald Trump falls on a vertiginous sliding scale of human behavior. It is that condition, an emo- tional state rather than a political state, that is at the heart of this book. HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_021123

Page 5 - HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_021124

BULLSEYE TT president made his familiar stink-in-the-room face, then wavi his hands as though to ward off a bug. “Don't tell me this,’ he said. “Why are you telling me this?” His personal lawyer John Dowd, in late February 2018, little mo than a year into Trump’s tenure, was trying to explain that prosecute were likely to issue a subpoena for some of the Trump Organizatio: business records. Trump seemed to respond less to the implications of such a deep di into his affairs than to having to hear about it at all. His annoyance set ¢ a small rant. It was not so much about people out to get him—and pe ple were surely out to get him—but that nobody was defending him. T. problem was his own people. Especially his lawyers. Trump wanted his lawyers to “fix” things. “Don't bring me problen bring me solutions,” was a favorite CEO bromide that he often repeate He judged his lawyers by their under-the-table or sleight-of-hand ski and held them accountable when they could not make problems disa pear. His problems became their fault. “Make it go away” was one of | frequent orders. It was often said in triplicate: “Make it go away, make go away, make it go away.” The White House counsel Don McGahn—representing the Whi HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_021124

Page 6 - HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_021125

2 MICHAEL WOLFF House rather than, in a distinction Trump could never firmly grasp, the president himself—demonstrated little ability to make problems disap- pear and became a constant brunt of Trump's rages and invective. His legal interpretation of proper executive branch function too often thwarted his boss's wishes. Dowd and his colleagues, Ty Cobb and Jay Sekulow—the trio of law- yers charged with navigating the president through his personal legal problems—had, on the other hand, become highly skilled in avoiding their client's bad humor, which was often accompanied by menacing, barely controlled personal attacks. All three men understood that to be a successful lawyer for Donald Trump was to tell the client what he wanted to hear. Trump harbored a myth about the ideal lawyer that had almost noth- ing to do with the practice of law. He invariably cited Roy Cohn, his old New York friend, attorney, and tough-guy mentor, and Robert Kennedy, John F. Kennedy’s brother. “He was always on my ass about Roy Cohn and Bobby Kennedy,” said Steve Bannon, the political strategist who, perhaps more than anyone else, was responsible for Trump's victory. “Roy Cohn and Bobby Kennedy, he would say. ‘Where’s my Roy Cohn and Bobby Kennedy?’” Cohn, to his own benefit and legend, built the myth that Trump continued to embrace: with enough juice and mus- cle, the legal system could always be gamed. Bobby Kennedy had been his brother’s attorney general and hatchet man; he protected JFK and worked the back channels of power for the benefit of the family. This was the constant Trump theme: beating the system. “I’m the guy who gets away with it,” he had often bragged to friends in New York. At the same time, he did not want to know details. He merely wanted his lawyers to assure him that he was winning. “We're killing it, right? That's what I want to know. That's all I want to know. If we're not killing it, you screwed up,’ he shouted one afternoon at members of his ad hoc legal staff. From the start, it had become a particular challenge to find top law- yers to take on what, in the past, had always been one of the most vaunted of legal assignments: representing the president of the United States. One high-profile Washington white-collar litigator gave Trump a list of twenty SIEGE issues that would immediately need to be addressed if he were to ta on the case. Trump refused to consider any of them. More than a doz major firms had turned down his business. In the end, Trump was left wi a ragtag group of solo practitioners without the heft and resources of t firms. Now, thirteen months after his inauguration, he was facing px sonal legal trouble at least as great as that faced by Richard Nixon and E Clinton, and doing so with what seemed like, at best, a Court Street les team. But Trump appeared to be oblivious to this exposed flank. Ratch: ing up his level of denial about the legal threats around him, he breez rationalized: “If I had good lawyers, I'd look guilty.” Dowd, at seventy-seven, had had a long, successful legal career, be in government and in Washington law firms. But that was in the past. ] was on his own now, eager to postpone retirement. He knew the imp« tance, certainly to his own position in Trump's legal circle, of und standing his client’s needs. He was forced to agree with the presider assessment of the investigation into his campaign’s contact with Russi state interests: it would not reach him. To that end, Dowd, and the otk members of Trump's legal team, recommended that the president coa erate with the Mueller investigation. “Tm not a target, right?” Trump constantly prodded them. This wasn’t a rhetorical question. He insisted on an answer, and affirmative one: “Mr. President, you're not a target.” Early in his tenu Trump had pushed FBI director James Comey to provide precisely tl reassurance. In one of the signature moves of his presidency, he had fir Comey in May 2017 in part because he wasn't satisfied with the enth siasm of the affirmation and therefore assumed Comey was plotti against him. Whether the president was indeed a target—and it would surely ha taken a through-the-looking-glass exercise not to see him as the bullse of the Mueller investigation—seemed to occupy a separate reality fr Trump’s need to be reassured that he was not a target. “Trump's trained me,’ Ty Cobb told Steve Bannon. “Even if it’s bz it’s great.” Trump imagined—indeed, with a preternatural confidence, nothi appeared to dissuade him—that sometime in the very near future he wot HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_021125

Sponsored

Page 7 - HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_021126

4 MICHAEL WOLFF hear directly from the special counsel, who would send him a compre- hensive and even apologetic letter of exoneration. “Where” he kept demanding to know, “is my fucking letter?” + + The grand jury empanelled by Special Counsel Robert Mueller met on Thursdays and Fridays in federal district court in Washington. Its busi- ness was conducted on the fifth floor of an unremarkable building at 333 Constitution Avenue. The grand jurors gathered in a nondescript space that looked less like a courtroom than a classroom, with prosecutors at a podium and witnesses sitting at a desk in the front of the room. The Mueller grand jurors were more female than male, more white than black, older rather than younger; they were distinguished most of all by their focus and intensity. They listened to the proceedings with “a scary sort of atten- tion, as though they already know everything,” said one witness. In a grand jury inquiry, you fall into one of three categories. You are a “witness of fact.” meaning the prosecutor believes you have information about an investigation at hand. Or you are a “subject,” meaning you are regarded as having personal involvement with the crime under investiga- tion. Or, most worrisome, you are a “target,” meaning the prosecutor is seeking to have the grand jury indict you. Witnesses often became sub- jects, and subjects often became targets. In early 2018, with the Mueller investigation and its grand jury main- taining a historic level of secrecy, no one in the White House could be sure who was what. Or who was saying what to whom. Anyone and everyone working for the president or one of his senior aides could be talking to the special counsel. The investigation’s code of silence extended into the West Wing. Nobody knew, and nobody was saying, who was spilling the beans. Almost every White House senior staffer—the collection of advisers who had firsthand dealings with the president—had retained a lawyer. Indeed, from the president's first days in the White House, Trump’ tangled legal past and evident lack of legal concern had cast a shadow on those who worked for him. Senior people were looking for lawyers even as they were still learning how to navigate the rabbit warren that is the West Wing. In February 2017, mere weeks after the inauguration, and not long SIEGE $ after the FBI had first raised questions about National Security Adv Michael Flynn, Chief of Staff Reince Priebus had walked into Steve I nons office and said, “I'm going to do you a big favor. Give me your ci card. Don't ask me why, just give it to me. You'll be thanking me fo1 rest of your life.” Bannon opened his wallet and gave Priebus his American Ext card. Priebus shortly returned, handed the card back, and said, “You have legal insurance.” Over the next year, Bannon—a witness of fact—spent hundrec hours with his lawyers preparing for his testimony before the sp: counsel and before Congress. His lawyers in turn spent ever moun hours talking to Mueller’s team and to congressional committee coun Bannons legal costs at the end of the year came to $2 million. Every lawyer's first piece of advice to his or her client was blunt unequivocal: talk to no one, lest it become necessary to testify about 1 you said. Before long, a constant preoccupation of senior staffers in Trump White House was to know as little as possible. It was a wre side-up world: where being “in the room” was traditionally the r sought-after status, now you wanted to stay out of meetings. You wa: to avoid being a witness to conversations; you wanted to avoid b witnessed being a witness to conversations, at least if you were sn Certainly, nobody was your friend. It was impossible to know whe colleague stood in the investigation; hence, you had no way of knox how likely it was that they might need to offer testimony about some else—you, perhaps—as the bargaining chip to save themselves by cc erating with the special counsel, a.k.a. flipping. The White House, it rapidly dawned on almost everyone who wo: there—even as it became one more reason not to work there—was scene of an ongoing criminal investigation, one that could potent ensnare anyone who was anywhere near it. + + + The ultimate keeper of the secrets from the campaign, the transition, through the first year in the White House was Hope Hicks, the W House communications director. She had witnessed most everyth HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_021126

Page 8 - HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_021127

6 MICHAEL WOLFF She saw what the president saw: she knew what the president, a man unable to control his own running monologue, knew. On February 27, 2018, testifying before the House Intelligence Committee—she had already appeared before the special counsel—she was pressed about whether she had ever lied for the president. Perhaps a more accomplished communications professional could have escaped the corner here, but Hicks, who had scant experience other than working as Donald Trump's spokesperson, which, as often as not, meant dealing with his disregard of empirical truth, found herself as though in a sudden and unexpected moral void trying to publicly parse the relative importance of her boss's lies. She admitted to telling “white lies.” as in, somehow, less than the biggest lies. This was enough of a forward admission to require a nearly twenty-minute mid-testimony conference with her lawyers, dis- tressed by what she might be admitting and by where any deconstruction of the president's constant inversions might lead. Not long after she testified, another witness before the Mueller grand jury was asked how far Hicks might go to lie for the president. The witness answered: “I think when it comes to doing anything as a ‘yes man’ for Trump, she'll do it—but she won't take a bullet for him” The statement could be taken as both a backhanded compliment and an estimate of how far loyalty in the Trump White House might extend—probably not too far. Almost no one in Trump’s administration, it could be argued, was con- ventionally suited to his or her job. But with the possible exception of the president himself, no one provided a better illustration of this unprepared and uninformed presidency than Hicks. She did not have substantial media or political experience, nor did she have a temperament annealed by years of high-pressure work. Always dressed in the short skirts that Trump favored, she seemed invariably caught in the headlights. Trump admired her not because she had the political skills to protect him, but for her pliant dutifulness. Her job was to devote herself to his care and feeding. “When you speak to him, open with positive feedback,” counseled Hicks, understanding Trump’s need for constant affirmation and his almost complete inability to talk about anything but himself. Her atten- tiveness to Trump and tractable nature had elevated her, at age twenty-nine, to the top White House communications job. And practically speaking, SIEGE 7 4 she acted as his de facto chief of staff. Trump did not want his administra- tion to be staffed by professionals; he wanted it to be staffed by people who attended and catered to him. Hicks—"Hope-y,’ to Trump—was both the president's gatekeeper and his comfort blanket. She was also a frequent subject of his pruri- ent interest: Trump preferred business, even in the White House, to be personal. “Who's fucking Hope?” he would demand to know. The topic also interested his son Don Jr., who often professed his intention to “fuck Hope.” The president's daughter Ivanka and her husband, Jared Kushner, both White House senior advisers, expressed a gentler type of concern for Hicks; sometimes they would even try to suggest eligible men. But Hicks, seeming to understand the insular nature of Trumpworld, dated exclusively inside the bubble, picking the baddest boys in it: cam- paign manager Corey Lewandowski during the campaign and presiden- tial aide Rob Porter in the White House. As the relationship between Hicks and Porter unfolded in the fall of 2017, knowing about the affair became an emblem of Trump insiderness, with special care taken to keep this development from the proprietary president. Or not: other people, assuming that Porter's involvement with Hicks would not at all please Trump, were less than discreet about it. + In the heightened enmity of the Trump White House, Rob Porter may have succeeded in becoming the most disliked person by everyone except per- haps the president himself. A square-jawed, 1950s-looking guy who could have been a model for Brylcreem, he was almost a laughable figure of betrayal and perfidy: if he hadn’t stabbed you in the back, you would be forced to acknowledge how unworthy he considered you to be. A sitcom sort of suck-up—“Eddie Haskell,” cracked Bannon, citing the early televi- sion icon of insincerity and brownnosing featured in Leave It to Beaver—he embraced Chief of Staff John Kelly, while at the same time poisoning him with the president. Porter’s estimation of his own high responsibilities in the White House, together with the senior-most jobs that the president, he let it be known, was promising him, seemed to put the administration and the nation squarely on his shoulders. HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_021127

Page 9 - HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_021128

8 MICHAEL WOLFF Porter had, before the age of forty, two bitter ex-wives, at least one of whom he had beaten, and both of whom he had cheated on at talk- of-the-town levels. During a stint as a Senate staffer, the married Porter had an affair with an intern, costing him his job. His girlfriend Samantha Dravis had moved in with Porter in the summer of 2017, while, quite unbeknownst to her, he was seeing Hicks. “I cheated on you because you're not attractive enough,” he later told Dravis. In a potentially criminal break of protocol, Porter had gained access to his raw FBI clearance reports and seen the statements of his ex-wives. His most recent ex-wife had also written a blog about his alleged abuse, which, while it did not name him, clearly fingered him. Concerned about the damaging impact his former wives could have on his security review, he recruited Dravis to help him smooth his relationship with both women. Lewandowski, Hicks’s former boyfriend, caught wind of the Hicks- Porter relationship and began working to expose it; by some reports, he got paparazzi to follow Hicks. Though Porter’s history of abuse was slowly making its way to the surface as a result of the FBI investigation, the Lewandowski campaign against Hicks cut through many other efforts to cover up Porter’s transgressions. Dravis, in the autumn of 2017, heard the Lewandowski-pushed rumors of the Hicks-Porter relationship. After finding Hicks’s number listed under a man’s name in Porter's contacts, Dravis confronted Porter, who promptly threw her out. Moving back in with her parents, she began her own revenge campaign, openly talking about Porter's security clear- ance issues, including to people inside the White House counsel's office, saying he had protection at the highest levels in the White House. Then, along with Lewandowski, Dravis helped leak the details of the Hicks- Porter romance to the Daily Mail, which published a story about it on February 1. But Dravis, joined by Porter's former wives, decided that, outra- geously, he had come out looking good in the Daily Mail account—he was part of a glam power couple! Porter called Dravis to taunt her: “You thought you could get me!” Dravis and his former wives all then publicly revealed their abuse at his hand. His first wife said he kicked and punched her; she even produced a photograph of her black eye. His second wife SIEGE - informed the media that she had filed an emergency protective orc against him. The White House, or at least Kelly—and likely Hicks—had been aw: of many of these claims and, effectively, covered them up. (“You usua have enough competent people for White House positions to weed out t wife beaters, but you couldn't be so choosy in the Trump White House,’ sz one Republican acquaintance of Porter's.) The furor that erupted arou Porter and his troubling gross-guy history not only annoyed Trump “He stinks of bad press”—it further weakened Kelly. On February 7, af both of his former wives gave interviews to CNN, Porter resigned. A publicity-shy Hicks—Donald Trump put a high value on associa’ who did not steal his press opportunities—suddenly found her love | in the glare of intense international press scrutiny. Her affair with the d credited Porter highlighted her own odd relationship with the preside and his family, as well as the haphazard management, interpersonal d: functions, and general lack of political savvy in the Trump court. + + The affair was, curiously, among the least of Hicks’s problems. Indeed, 1 Hicks the Porter scandal became perhaps a better cloud under which leave the administration than what almost everybody in the West Wi assumed was the real cloud. On February 27, a reporter at the Washington insider newsletter Axi Jonathan Swan, a favorite conduit for White House leaks, reported tl Josh Raffel was leaving the White House. In a novel arrangement, Rai had come into the White House in April 2017 as the exclusive spokespers for the president's son-in-law Jared Kushner, and his wife, Ivanka, bypa ing the White House communications team. Raffel, who, like Kushn was a Democrat, had worked for Hiltzik Strategies, the New York pub relations firm that represented Ivanka’s clothing line. Hope Hicks, who had also worked for the Hiltzik firm—perhaps b. known for having long represented the film producer Harvey Weinste caught, in the fall of 2017, in an epochal harassment and abuse scanc and cover-up—had originally had the same role as Raffel but at a higt level: she was the personal spokesperson for the president. In Septemb HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_021128

Sponsored

Page 10 - HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_021129

10 MICHAEL WOLFF Hicks had been elevated to White House communications director, with Raffel as her number two. The trouble had arisen the previous summer. Both Hicks and Raffel had been on Air Force One in July 2017 as the news broke about Donald Trump Jr-s meeting in Trump Tower during the campaign with Russian government go-betweens offering dirt on Hillary Clinton. During the flight back to the United States after the G20 summit in Germany, Hicks and Raffel aided the president in his efforts to issue a largely false story about the Trump Tower meeting, thus becoming part of the cover-up. Even though Raffel had been at the White House for a little more than nine months, the Axios report said that his departure had been under dis- cussion for several months. That was untrue. It was an abrupt exit. The next day, just as abruptly, Hope Hicks—the person in the White House closest to the president—resigned as well. The one person who perhaps knew more than anyone else about the workings of the Trump campaign and the Trump White House was sud- denly out the door. The profound concern inside the White House was the reasonable supposition that Hicks and Raffel, both witnesses to and participants in the president's efforts to cover up the details of his son and son-in-law’s meeting with the Russians, were subjects or targets of the Mueller investigation—or, worse, had already cut a deal. The president, effusive in his public praise for Hicks, did not try to talk her out of leaving. In the weeks to come he would mope about her absence—“Where’s my Hope-y?”—but, in fact, as soon as he got wind that she might be talking, he wanted to cut her loose and began, in a significant rewrite, downgrading her status and importance on the cam- paign and in the White House. Yet here, from Trump's point of view, was a hopeful point about Hicks: as central as she was to his presidency, her duties really only consisted of pleasing him. She was an unlikely agent of grand strategy and great con- spiracies. Trumps team was made up of only bit players. e+ John Dowd may have been reluctant to give his client bad news, but he well understood the danger of a thorough prosecutor with virtually SIEGE unlimited resources. The more a determined team of G-men sifts, strit and inspects, the greater the chance that both methodical and cast crimes will be revealed. The more comprehensive the search, the mc inevitable the outcome. The case of Donald Trump—with his history bankruptcies, financial legerdemain, dubious associations, and genei sense of impunity—certainly seemed to offer prosecutors something an embarrassment of riches. For his part, however, Donald Trump yet seemed to believe that | skills and instincts were at least a match for all the thoroughness a resources of the United States Department of Justice. He even believ their exhaustive approach would work in his favor. “Boring. Confusi for everybody,’ he said, dismissing the reports of the investigation pr vided by Dowd and others. “You can't follow any of this. No hook? One of the many odd aspects of Trump's presidency was that did not see being president, either the responsibilities or the exposu as being all that different from his pre-presidential life. He had endur almost countless investigations in his long career. He had been involv in various kinds of litigation for the better part of forty-five years. He w a fighter who, with brazenness and aggression, got out of fixes that wot have ruined a weaker, less wily player. That was his essential busin: strategy: what doesn’t kill me strengthens me. Though he was wound again and again, he never bled out. “It's playing the game,” he explained in one of his frequent mor logues about his own superiority and everyone else's stupidity. “I’m go at the game. Maybe I’m the best. Really, I could be the best. I think I< the best. I’m very good. Very cool. Most people are afraid that the wo might happen. But it doesn’t, unless you're stupid. And I’m not stupid? In the weeks after his first anniversary in office, with the Muel investigation in its eighth month, Trump continued to regard the s} cial counsel's inquiry as a contest of wills. He did not see it as a war attrition—a gradual reduction of the strength and credibility of the t get through sustained scrutiny and increasing pressure. Instead, he sav situation to confront, a spurious government undertaking that was v nerable to his attacks. He was confident he could jawbone this “wit hunt”—often tweeted in all-caps—to at least a partisan draw. HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_021129

Page 11 - HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_021130

12 MICHAEL WOLFF He remained irritated by efforts to persuade him to play the game in the usual Washington way—mounting a disciplined legal defense, negoti- ating, trying to cut his losses—rather than his way. This was disconcerting to many of the people closest to him, but it alarmed them more to see that as Trump's indignation and sense of personal insult rose, so did his belief in his own innocence. OF By the end of February, in addition to the Mueller grand jury indictments of a group of Russian nationals for illegal activities involved with efforts by the Russian government to influence the US. election, Mueller had reached several levels into the Trump circle. Among those who were indicted or who had pled guilty to felonies were his former campaign man- ager Paul Manafort, his former national security advisor Michael Flynn, the eager-beaver junior adviser George Papadopoulos, and Manafort's business partner and campaign official Rick Gates. This series of legal moves could be classically read as a methodical, step-by-step approach to the president's door. Or, from the Trump camp's point of view, it could be seen as a roundup of the sorts of opportunists and hangers-on who had always trailed Trump. The doubts about the usefulness of Trump’s hangers-on was an implicit part of their usefulness: they could be shrugged off and disavowed at any time, which is what promptly happened at the least sign of trouble. The Trumpers swept up by Mueller were all declared wannabe and marginal players. The president had never met them, could not remember them, or had a limited acquaintance with them. “I know Mr. Manafort—I haven't spoken to him in a long time, but I know him,” declared a dismissive Trump, pulling a line from the “who dat?” page of his playbook. The difficulty in proving a conspiracy is proving intent. Many of the president's inner circle believed that Trump, and the Trump Organiza- tion, and by extension the Trump campaign, operated in such a diffuse, haphazard, gang-that-couldn’t-shoot-straight manner that intent would be very difficult to establish. What's more, the Trump hangers-on were so demonstrably subpar players that stupidity could well be a reasonable defense against intent. SIEGE - 12 Many in the Trump circle agreed with their boss: they believed tha whatever idiotic moves had been made by idiotic Trump hands, the Rus: sia investigation was too abstruse and nickel-and-dime to ultimately stick At the same time, many, and perhaps all, were privately convinced tha a deep dive—or, for that matter, even a cursory inspection—of Trump financial past would yield a trove of overt offenses, and likely a pattern o career corruption. It was hardly surprising, then, that ever since the beginning of th special counsel's investigation, Trump had tried to draw a line in the san: between Mueller and Trump family finances, openly threatening Muelle if he went there. Trumps operating assumption remained that the speciz counsel was afraid of him, conscious of where and how his toleranc might’end. Trump was confident that the Mueller team could be made t understand its limits, by either wink-wink or unsubtle threat. “They know they can't get me,’ he told one member of his circ] of after-dinner callers, “because I was never involved. I’m not a targe There's nothing. I’m not a target. They’ve told me, I’m not a target. An they know what would happen if they made me a target. Everybod understands everybody.’ OF Books and newspaper stories about Trump’s forty-five years in busine: were full of his shady dealings, and his arrival in the White House on. helped to highlight them and surface even juicier ones. Real estate wi the world’s favorite money-laundering currency, and Trump's B-level re estate business—relentlessly marketed by Trump as triple A—was qui explicitly designed to appeal to money launderers. What's more, Trumy own financial woes, and desperate efforts to maintain his billionaire lif style, cachet, and market viability, forced him into constant and unsubt schemes. In the high irony department, Jared Kushner, when he was : law school, and before he met Ivanka, identified, in a paper he wrot possible claims of fraud against the Trump Organization in a particul real estate deal he was studying—a subject now of quite some amuseme among his acquaintances at the time. Practically speaking, Trump hid plain sight, as the prosecutors appeared to be finding. HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_021130

Page 12 - HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_021131

14 MICHAEL WOLFF In November 2004, for instance, Jeffrey Epstein, the financier later caught in a scandal involving underage prostitutes, agreed to purchase from bankruptcy a house in Palm Beach, Florida, for $36 million, a prop- erty that had been on the market for two years. Epstein and Trump had been close friends—playboys in arms, as it were—for more than a decade, with Trump often seeking Epstein’s help with his chaotic financial affairs. Soon after negotiating the deal for the house in Palm Beach, Epstein took Trump to see it, looking for advice on construction issues involved with moving the swimming pool. But as he prepared to finalize his purchase for the house, Epstein discovered that Trump, who was severely cash- constrained at the time, had bid $41 million for the property and bought it out from under Epstein through an entity called Trump Properties LLC, entirely financed by Deutsche Bank, which was already carrying a substantial number of troubled loans to the Trump Organization and to Trump personally. Trump, Epstein knew, had been loaning out his name in real estate deals—that is, for an ample fee, Trump would serve as a front man to disguise the actual ownership in a real estate transaction. (This was, in a sense, another variation of Trump’s basic business model of licensing his name for commercial properties owned by someone else.) A furi- ous Epstein, certain that Trump was merely fronting for the real owners, threatened to expose the deal, which was getting extensive coverage in Florida papers. The fight became all the more bitter when, not long after the purchase, Trump put the house on the market for $125 million. But if Epstein knew some of Trump’s secrets, Trump knew some of Epstein’s. Trump often saw the financier at Epstein’s current Palm Beach house, and Trump knew that Epstein was visited almost every day, and had been for many years, by girls hed hired to give him massages that often had happy endings—girls recruited from local restaurants, strip clubs, and, also, Trump’s own Mar-a-Lago. Just as the enmity between the two friends increased over the house purchase, Epstein found himself under investigation by the Palm Beach police. And as Epstein’s legal prob- lems escalated, the house, with only minor improvements, was acquired for $96 million by Dmitry Rybolovlev, an oligarch who was part of the close Putin circle of government-aligned industrialists in Russia, and who, SIEGE 15 in fact, never moved into the house. Trump had, miraculously, earned $55 million without putting up a dime. Or, more likely, Trump merely earned a fee for hiding the real owner—a shadow owner quite possibly being funneled cash by Rybolovlev for other reasons beyond the value of the house. Or, possibly, the real owner and real buyer were one and the same. Rybolovlev might have, in effect, paid himself for the house, thereby cleansing the additional $55 million for the second purchase of the house. This was Donald Trump's world of real estate. % FF As though using mind-control tricks, Jared Kushner had become highly skilled at containing his deep frustration with his father-in-law. He stayed expressionless—sometimes he seemed almost immobile—when Trump went off the rails, unleashing tantrums or proposing dopey political or policy moves. Kushner, a courtier in a crazy court, was possessed of an eerie calmness and composure. He was also very worried. It seemed astounding and ludicrous that this fig-leaf technicality—“You're not a target, Mr. President”—could offer his father-in-law such comfort. Kushner understood that Trump was surrounded by a set of mortal arrows, any of which might kill him: the case for obstruction; the case for collusion; any close look at his long, dubious financial history; the always-lurking issues with women; the prospects of a midterm rout and the impeachment threat if the midterm elections went against them; the fickleness of the Republicans, who might at any time turn on him; and the senior staffers who had been pushed out of the administration (Kushner had urged the ouster of many of them), any of whom might testify against him. In March alone, Gary Cohn, the president's chief economic adviser, Rex Tillerson, the secretary of state, and Andrew McCabe, the deputy director of the FBI—each man bearing the president deep contempt— were pushed from the administration. But the president was in no mood to hear Kushner’s counsel. Never entirely trusted by his father-in-law—in truth, Trump trusted no one except, arguably, his daughter Ivanka, Kushner’s wife—Kushner now found himself decidedly on the wrong side of Trump’ red line of loyalty. HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_021131

Sponsored

Page 13 - HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_021132

16 MICHAEL WOLFF As a family insider, Kushner, in a game of court politics so vicious that, in another time, it might have yielded murder plots, had appeared to triumph over his early White House rivals. But Trump invariably soured on the people who worked for him, just as they soured on him, not least because he nearly always came to believe that his staff was profiting at his expense. He was convinced that everyone was greedy, and that sooner or later they would try to take what was more rightfully his. Increasingly, it seemed that Kushner, too, might be just another staff member trying to take advantage of Donald Trump. Trump had recently learned that a prominent New York investment fund, Apollo Global Management, led by the financier Leon Black, had provided the Kushner Companies—the family real estate group that had been managed by Kushner himself while his father, Charlie, was in federal prison—with $184 million in financing. This was troubling on many levels, and it left a vulnerable Kushner open to more questions about the conflicts between his business and his position in the White House. During the transition, Kushner had offered Apollo's cofounder Marc Rowan, the job of director of the Office of Man- agement and Budget. Rowan initially accepted the job, declining it only after Apollo chairman Leon Black objected to what would have to be dis- closed about Rowan’s and the firms investments. But the president-elect's concerns were elsewhere: he was more keenly and furiously focused on the fact that, in the constant search for financings that occur in mid-tier real estate companies like Trump's, Apollo had never extended itself for the Trump Organization. Now, it seemed baldly appar- ent, Apollo was backing the Kushners solely because of the family’s con- nection to the administration. The constant accounting in Trump's head of who was profiting from whom, and his sense of what he was therefore owed for creating the circumstances by which everyone could profit, was one of the things that reliably kept him up at night. “you think I don’t know what's going on?” Trump sneered at his daughter, one of the few people he usually went out of his way to try to mollify. “You think I don’t know what's going on?” The Kushners had gained. He had not. The president’s daughter pleaded her husband’s case. She spoke of the SIEGE incredible sacrifice the couple had made by coming to Washington. Ai for what? “Our lives have been destroyed,’ she said melodramatically and yet with some considerable truth. The former New York socialit had been reduced to potential criminal defendants and media laughir stocks. After a year of friends and advisers whispering that his daughter a son-in-law were at the root of the disarray in the White House, Trur once again was thinking they should never have come. Revising histo he told various of his late-night callers that he had always thought tk never should have come. Over his daughter’s bitter protests, he declin to intercede in his son-in-law’s security clearance issues. The FBI h continued to hold up Kushner’s clearance—which the president, at discretion, could approve, his daughter reminded him. But Trump « nothing, letting his son-in-law dangle in the wind. Kushner, with superhuman patience and resolve, waited for his opp tunity. The trick among Trump whisperers was how to focus Trur attention, since Trump could never be counted on to participate in a thing like a normal conversation with reasonable back-and-forth. Spc and women were reliable subjects; both would immediately engage h: Disloyalty also got Trump’s attention. So did conspiracies. And mone: always money. | + % Kushner’s own lawyer was Abbe Lowell, a well-known showboat of D.C. criminal bar who prided himself on, and managed his clients’ exp tations and attention with, an up-to-the-minute menu of rumors : insights about what gambit or strategy prosecutors were about to dish The true edge provided by a high-profile litigator was perhaps not cot room skill but backroom intelligence. Lowell, adding to the reports Dowd had received, told Kushner 1 prosecutors were about to substantially deepen the presidents—and Trump family’s—jeopardy. Dowd had continued to try to mollify the pr dent, but Kushner, with intel supplied by Lowell, went to his father-in-law v reports about this new front in the legal war against him. Sure enough. March 15 the news broke that the special counsel had issued a subpo HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_021132

Page 14 - HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_021133

for the Trump Organization records: it was a deep and encompassing order, reaching many years back. Kushner also warned his father-in-law that the investigation was about to spill over from the Mueller team, with its narrow focus on Russian collu- sion, to the Southern District of New York—that is, the federal prosecutor's office in Manhattan—which would not be restricted to the Russia probe. This was a work-around intended to circumvent the special counsel's restriction to Russia-related matters, but also an effort by the Mueller team to short- circuit any attempt by the president to disband or curtail its investiga- tion. By moving parts of the investigation to the Southern District, Mueller, as Kushner explained to Trump, was ensuring that the investigation of the president would continue even without the special counsel. Mueller was playing a canny, or ass-protecting, game, while also following precise pro- cedures: even as he focused on the limited area of his investigation, he was divvying up evidence of other possible crimes and sending it out to other jurisdictions, all of which were eager to be part of the hunt. It gets worse, Kushner told Trump. The Southern District was once run by Trump's friend Rudy Giuliani, the former mayor of New York. In the 1980s, when Giuliani was the federal prosecutor—and when, curiously, James Comey had worked for him— the Southern District became the premier prosecutor of the Mafia and of Wall Street. Giuliani had pioneered using a draconian, and many believed unconstitutional, interpretation of the RICO (Racketeer Influenced and Corrupt Organizations) Act against the Mob. He used the same interpre- tation against big finance, and in 1990 the threat of a RICO indictment, under which the government could almost indiscriminately seize assets, brought down the investment bank Drexel Burnham Lambert. The Southern District had long been worrisome to Trump. After his election, he had an unseemly meeting with Preet Bharara, the federal pros- ecutor there, a move whose optics were alarming to all of his advisers, including Don McGahn and the incoming attorney general, Jeff Sessions. (The meeting foreshadowed the one Trump would shortly have with Comey, during which he sought a pledge of loyalty in return for job secu- rity.) His meeting with Bharara was unsatisfactory: Bharara was unwill- SIEGE : 19 ing to humor him—or, shortly, even to return his calls. In March 2017, Trump fired him. Now, said Kushner, even without Bharara, the Southern District was looking to treat the Trump Organization as a Mob-like enterprise; its law- yers would use the RICO laws against it and go after the president as if he were a drug lord or Mob don. Kushner pointed out that corporations had no Fifth Amendment privilege, and that you couldn't pardon a corpora- tion. As well, assets used in or derived from the commission of a crime could be seized by the government. In other words, of the more than five hundred companies and separate entities in which Donald Trump had been an officer, up until he became president, many might be subject to forfeiture. One potential casualty of a successful forfeiture action was the president's signature piece of real estate: the government could seize Trump Tower. +t 4 In mid-March, a witness with considerable knowledge of the Trump Organization's operations traveled by train to Washington to appear before the Mueller grand jury. Picked up at Union Station by the FBI, the wit- ness was driven to the federal district court. From 10:00 a.m. to 5:00 p.m., two prosecutors on the Mueller team, Aaron Zelinsky and Jeannie Rhee, reviewed with the witness, among other issues, the structure of the Trump Organization. The prosecutors asked the witness about the people who regularly talked to Trump, how often they met with him, and for what purposes. They also asked how meetings with Trump were arranged and where they took place. The witness’s testimony yielded, among other useful pieces of information, a signal fact: all checks issued by the Trump Organization were personally signed by Donald Trump himself. The Trump Organization's activities in Atlantic City were a particular subject of interest that day. The witness was asked about Trump’s rela- tionship with known Mafia members—not if he had such relationships, but the nature of the relationships prosecutors already knew existed. The prosecutors also wanted to know about Trump Tower Moscow, a project HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_021133

Page 15 - HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_021134

20 MICHAEL WOLFF pursued by Trump for many years—pursued, in fact, well into the 2016 campaign—albeit never brought to fruition. Michael Cohen, Trump's personal lawyer and a Trump Organization officer, was another significant topic. The prosecutors asked questions about the level of Cohen's disappointment at not being included in the president's White House team. They seemed to be trying to gauge how much resentment Cohen felt, which led the witness to infer that they wanted to estimate how much leverage they might have if they attempted to flip Michael Cohen against the president. Zelinsky and Rhee wanted to know about Jared Kushner. And they wanted to know about Hope Hicks. ‘The two prosecutors also delved into the president’s personal life. How often did he cheat on his wife? With whom? How were trysts arranged? What were the president's sexual interests? The Mueller investigation, and its grand jury, was becoming a clearing house for the details of Trump's long history of professional and personal perfidiousness. When the long day was finally over, the witness left the grand jury room shocked—not so much by what the prosecutors wanted to know but by what they already knew. + By the third week of March, Trump's son-in-law had the president's full attention. “They can not only impeach you, they can bankrupt you” was Kushner’s message. Agitated and angry, Trump pressed Dowd for more reassurances, holding him accountable for the prior reassurances Trump had frequently demanded he be given. Dowd held firm: he yet believed that the fight was in its early stages and that Mueller was still on a fishing expedition. But Trump's patience was finally at an end. He decided that Dowd was a fool and should go back into the retirement from which, Trump kept repeating, he had rescued him. Indeed, resisting that retirement, Dowd pleaded his own case, assuring the president that he could continue to provide him with valuable help. To no avail: on March 22, Dowd reluc- tantly resigned, sending another bitter former Trumper into the world. = THE DO-OVER he day John Dowd was fired, Steve Bannon was sitting at his dinin; room table trying to forestall another threat to the Trump pres dency. This one wasn't about a relentless prosecutor but rather a betraye base. It was about the Wall that wasn't. The town houses on Capitol Hill, middle-class remnants of the nin teenth century, are cramped up-and-down affairs of modest parlor floo: nook-y sitting rooms, and small bedrooms. Many serve as headquarte for causes and organizations that can’t afford Washington's vast amou of standard-issue office real estate. Some double as housing for th: organization's leaders. Many represent amateur efforts or eccentric pt suits, often a kind of shrine to hopes and dreams and revolutions yet occur. The “Embassy” on A Street—a house built in 1890 and the form location of Bannon’s Breitbart News—was where Bannon had lived a worked since his exile from the White House in August 2017. It was p frat house, part man cave, and part pseudo-military redoubt; conspiré literature was scattered about. Various grave and underemployed you men, would-be militia members, loitered on the steps. The Embassy’s creepiness and dark heart were in quite stark contr to Bannon’s expansive and merry countenance. He might be in exile fr the Trump White House, but it was an ebullient banishment, coffee-fue or otherwise. HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_021134

Sponsored

Page 16 - HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_021135

22 MICHAEL WOLFF In the last few weeks, he had helped install his allies—and first-draft choices during the presidential transition—in central posts in the Trump administration. Mike Pompeo had recently been named secretary of state, John Bolton would soon become the national security advisor, and Larry Kudlow had been appointed director of the National Economic Council. The president's chief political aides were Corey Lewandowski and David Bossie, both Bannon allies, if not acolytes; both operated outside the White House and were frequent visitors at the Embassy. Many of the daily stream of White House defenders on cable television—the surrogates— were Bannon people carrying Bannon’s message as well as the president's. What's more, his enemies in the White House were moving out, includ- ing Hope Hicks, H. R. McMaster, the former national security advisor, and the ever shrinking circle of allies supporting the president's son-in- law and daughter. Bannon was often on the road. He was in Europe meeting with the rising populist right-wing groups, and in the U.S. meeting with hedge funders desperate to understand the Trump variable. He was also looking for every opportunity to try to convince liberals that the populist way ought to be their way, too. Early in the year, Bannon went to Cambridge to see Larry Summers, who had been Bill Clinton's Treasury secretary, Barack Obama's director of the National Economic Council, and, for a time, president of Harvard. Summers's wife refused to allow Bannon into their home, so the meeting happened at Harvard instead. Summers was mis-shaven and wearing a shirt that was missing a button or two, while Bannon was sporting his double-shirt getup, cargo pants, and a hunting jacket. “Both of them looked like Asperger guys,” said one of the people at the meeting. “Do you fucking realize what your fucking friend is doing?” yelled Summers about Trump and his administration. “You're fucking the country!” “You elite Democrats—you only care about the margins, people who are rich or people who are poor” returned Bannon. “Your trade mumbo jumbo will sink the world into a depression, thundered Summers. “And you've exported U.S. jobs to China!” declared a delighted Ban- el SIEGE 23 non, always enjoying the opportunity to joust with a member of the establishment. Bannon was—or at least saw himself to be—a fixer, power broker and kingmaker without portfolio. He was a cockeyed sort of Clark Clifford, that political eminence and influence peddler of the 1960s anc 70s. Or a wise man of the political fringe, if that was not an ultimate kinc of contradiction. Or the head of an auxiliary government. Or, perhaps something truly sui generis: no one quite like Bannon had ever playec such a central role in America’s national political life, or been such a thorr in the side of it. As for Trump, with friends like Bannon, who needec enemies? ‘The two men might be essential to each other, but they reviled anc ridiculed each other, too. Bannon’s constant public analysis of Trump: confounding nature—both its comic and harrowing components, thi behavior of a crazy uncle—not to mention his indiscreet diatribes or the inanities of Trumps family, continued to further alienate him from th: president. And yet, though the two men no longer spoke, they hung o1 each other’s words—each desperate to know what one was saying abou the other. Whatever current feeling Bannon might have for Trump—his moox ranged from exasperation to fury to disgust to incredulity—he contin ued to believe that nobody in American politics could match Trump’ midway-style showmanship. Yes, Donald Trump had restored showman ship to American politics—he had taken the wonk out of politics. In sum he knew his audience. At the same time, he couldn't walk a straight line Every step forward was threatened by his next lurch. Like many grea actors, his innate self-destructiveness was always in conflict with his kee1 survival instincts. Some around the president merely trusted that th latter would win over the former. Others, no matter the frustration o the effort, understood how much he needed to be led by unseen hands— unseen being the key attribute. With no one to tell him otherwise, Bannon continued, unseen, t conduct the president’s business from his dining-room table on A Street +b HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_021135

Page 17 - HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_021136

24 MICHAEL WOLFE That afternoon, a bipartisan Congress with surprising ease had passed the $1.3 trillion 2018 appropriations bill. “McConnell, Ryan, Schumer, and Pelosi,” said Bannon about the Republican and Democratic congressional leadership, “in their singular moment of bipartisan magnanimity, put one over on Trump.” This legislative milestone was a result of Trump's disengagement and everybody else's attentive efforts. Most presidents are eager to get down into the weeds of the budget process. Trump took little or no interest. Hence the Republican and Democratic leadership—here supported by the budget and legislative teams in the White House—were able to pass an enormous spending bill that failed to fund Trumps must-must item, the holy grail Wall, that prospective two-thousand-mile monument meant to run the entire length of the border between the United States and Mexico. Instead, the bill provided only $1.6 billion for border security. The current bill was in effect the same budget bill that had been pushed forward at the end of the previous September, when the Wall had once again not been funded. In the fall, Trump had agreed to have the Republican-controlled Congiess vote to extend the September budget bill. The next time it came up, the Wall would be funded or, he threatened, the government would be shut down. Even the hardest-core Trumpers in Congress seemed content not to have to die on the actual battlefield of funding the Wall, since that would mean embracing or at least enduring an always politically risky shutdown. Trump, too, in his way, seemed to understand that the Wall was more myth than reality, more slogan than actual plan. The Wall was ever for another day. On the other hand, it was unclear what the president understood. “We've gotten the budget,” he privately told his son-in-law at the end of the March budget negotiations. “We've gotten the Wall, totally.” OF On Wednesday, March 21, the day before the final vote, Paul Ryan, the Speaker of the House, had come to the White House to receive the presi- dent's blessings on the budget bill. “Got $1.6 Billion to start Wall on Southern Border, rest will be forth- coming,’ the president shortly tweeted. SIEGE 25 The White House had originally asked for $25 billion for the Wall, although high-end estimates of the Wall’s ultimate cost came in at $70 billion. Even then, the $1.6 billion in the appropriations bill was not so much for the Wall as for better security measures. As the final vote neared, a gentlemen's agreement appeared to have been reached, one that extended to every corner of the government— with, it even seemed, Trump's own tacit support, or at least his conve- nient distraction. The understanding was straightforward: whatever their stripe, members of Congress would not blow up the appropriations pro- cess for the Wall. There were, too, Republicans like Ryan—with the backing of Repub- lican donors such as Paul Singer and Charles Koch—who were eager to walk back, by whatever increment possible, Trump's hard-line immigra- tion policies and rhetoric. Ryan and others had devised a simple method for accomplishing this kind of objective: you agreed with him and then ignored him. There was happy talk, which Trump bathed in, followed by practical steps, which bored him. That Wednesday, Trump made a series of calls to praise everyone’s work on the bill. The next morning, Ryan, in a televised news conference to seal the deal, said, “The president supports this bill, there's no two ways about it.” Here were the twin realities. The Wall was the most concrete manifesta- tion of Trumpian policy, attitude, belief, and personality. At the same time, the Wall forced every Republican politician to come to terms with his or her own common sense, fiscal prudence, and political flexibility. It was not just the expense and impracticality of the Wall, it was hav- ing to engage in a battle for it. A government shutdown would mean a high-stakes face-off between the Trump world and the non-Trump world Should this come to pass, it would potentially be as dramatic a moment as any that had occurred since the election of 2016. If the Democrats wanted to harden the partisan division and were eager to find yet another example—perhaps the mother of all exam- ples—of Trump at his most extreme, a shutdown over the Wall woulc hand them one. If the Republicans wanted to shift the focus from a full barbarian Trump to, say, the tax bill the Congress had recently passed HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_021136

Page 18 - HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_021137

26 MICHAEL WOLFF shutting down the government would sweep that approach right off the table. The White House, quite behind Trump’s back, was aggressively work- ing to pass the appropriations bill and avoid a shutdown. The vice presi- dent gave Trump the same assurance he had been given previously when a budget had been passed without full funding for the Wall: Pence said the bill provided a “down payment” for the Wall, a phrase whose debt-finance implications seemed to amply satisfy the president and which he repeated with great enthusiasm. Marc Short, the White House director of legisla- tive affairs, and Mick Mulvaney, the director of the Office of Manage- ment and Budget, in a joint appearance in the White House briefing room that Thursday, shifted the debate from the Wall to the military. “This bill will provide the largest year-over-year increase in defense spending since World War II,” said Mulvaney. “It'll be the largest increase for our men and women in uniform in salary in the last ten years.” +b The attempt to distract the Trumpian base with these bromides utterly failed. The hard-core cadre insisted on forcing the issue, and Bannon was delighted to serve as their general. Within minutes of the budget bill’s passage on March 22, Bannon, in the Embassy, began working the phones. Calling Trump's most ardent supporters, his goal was to “light him up” The effect was nearly imme- diate: an unsuspecting Trump started to hear from many of those on his noisy back bench, who were suddenly furious. Bannon understood what moved Trump. Details did not. Facts did not. But a sense that something valuable might be taken from him immediately brought him up on his hind legs. If you confronted him with losing, he would turn on a dime. Indeed, turning on a dime was his only play. “It’s not that he needs to win the week, or day, or even the hour” reflected Bannon. “He needs to win the second. After that, he drifts” For the hard-core Trumpers, it was back to a fundamental through line of Trumpism: you had to constantly remind Trump which side he was on. As Bannon organized a howling protest from the president's base, SIEGE 27 he took stock of the Trump reality: “There simply is not going to be a Wall, ever, if he doesn't have to pay a political price for there not being a Wall” If the Wall was not under way by the midterm elections in Novem- ber, it would show Trump to be false and, worse, weak. The Wall needed to be real. The absence of the Wall in the spending bill was just what it seemed to be: Trump out to lunch. Trump's most effective message, the forward front of the Trump narrative—maximal aggression toward ille- gal immigrants—had been muted. And this had happened without him knowing it. OF The night of the twenty-second, the Fox News lineup—Tucker Carlson, Laura Ingraham, and Sean Hannity—hammered the message: betrayal. The battle was on. The Republican leadership on the Hill, along with the donor class, stood sober and pragmatic in the face of both political realities and the prospect of unlimited billions in government spending— with, certainly, no illusions that Mexico was going to pay for the Wall. Opposing them were the Fox pundits, righteous and unyielding in their appeal to the true emotion of Trumpism. The personal transformation of Trump over the course of the evening was convulsive. All three Fox pundits delivered a set of electric shocks. each rising in current. Trump had sold out the movement. Or, worse. Trump had been outsmarted and outwitted. Trump, on the phone, roared in pain and fury. He was the victim. He had no one in his corner. He could trust no one. The congressional leadership: against him. The White House itself: against him. Betrayal? Almost everyone in the White House hac betrayed him. The next morning it got worse. Pete Hegseth, the most obsequious o: the Fox Trump lovers, seemed, on Fox & Friends, nearly brought to tear: by Trump's treachery. Then, almost simultaneously with Hegseth’s wailing, Trump abruptly— confoundingly—shifted position and tweeted that he was considering vetoing the appropriations bill. The same bill that, twenty-four hours before, he had embraced. ' HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_021137

Sponsored

Page 19 - HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_021138

28 MICHAEL WOLFF That Friday morning, he came down from the residence into the Oval Office in a full-on rage so violent that, for a moment, his hair came undone. To the shock of the people with him, there stood an almost entirely bald Donald Trump. The president’s sudden change of heart sent the entire Republican Party into a panic. If Trump carried out his threat not to sign the bill, he would bring on what they most feared: a shutdown. And he might well blame the shutdown on his own party. Mark Meadows, the head of the House Freedom Caucus and a | staunch Trump ally in Congress, called the president from Europe to say that after the vote on Thursday afternoon most members had left town for the congressional recess. Congress wouldn't be able to undo the previous day’s vote, and the shutdown was due to commence in mere hours. Mitch McConnell rushed Defense Secretary Jim Mattis into action to tell the president that American soldiers would not be paid the next day if he didn't sign the bill. This was a repeat performance: Mattis had issued a similar warning during a threatened shutdown in January. “Never... never... never... again; Trump shouted, pounding the desk after each “never.” Once again he caved and agreed to sign the bill. But he vowed that next time there would be billions upon billions for the Wall or there really would be a shutdown. Really. Really. * Bannon had been here before, so many times. “Dude, he’s Donald fucking Trump,’ said Bannon, holding his head and sitting at his table in the Embassy the day after the president signed the bill. Bannon was not confused: he had a clear understanding of how great a liability Trump could be to Bannon’s own vision and career. To the ner- vous titers of the people around him, Bannon believed he was the man of populist destiny and not Donald Trump. The urgency here was real. Bannon believed he represented the workingman against the corporate-governmental-technocratic machine whose constituency was the college-educated. In Bannon’s romantic view, oe ] SIEGE 29 the workingman smelled of cigarettes, crushed your hand in his, and was hard as brick—and not from working out in a gym. This remembrance of things past, of (if it ever existed) a leveled world where a workingmar was proud of his work and identity, was inspiring, Bannon believed, : global anger. It was a revolution—this worldwide unease and fear anc day-by-day upending of liberal assumptions—and it was his. The globa hegemon was in his sights. He was the man behind the curtain—and h might as well be in front of it, too—trying to snatch the world back fron its postmodern anomie and restore something like the homogenized an: neighborly embrace of 1962. And China! And the coming Gétterdammerung! To Bannon, thi was way-of-life stuff. China was the Russia of 1962—but smarter, mor tenacious, and more threatening. American hedge funders, in their secre support of China against the interests of the American middle class, wet the new fifth column. How much of this did Trump understand? How much was Trum committed to the ideas that moved Bannon and, by some emotion osmosis, the base? Trump was more than a year in, and not a shovelful dirt had yet been dug for the Wall, nor a penny allocated. The Wall ar so much else that was part of Bannon’s populist revolution—the detai of which he had once listed on whiteboards in his White House offic expecting to check each one off—were entirely captive to Trump's inatte: tion and wild mood swings. Trump, Bannon had long ago learned, “does: give a fuck about the agenda—he doesn't know what the agenda is.” 4% + In late March, after the gloom of the budget bill disaster had lifted, the was a brief, optimistic moment for the faithful in Trump’s inner circle. Chief of Staff John Kelly, fed up with Trump—just as Trump was f up with him—seemed surely on the way out. Kelly had joined the Wh House, replacing Reince Priebus, Trump’s first chief of staff, in Aug) 2017, charged with bringing management discipline to a chaotic W Wing. But by mid-fall, Trump was circumventing Kelly’s new prox dures. Jared and Ivanka—with many of the new rules designed to c' tail their open access to the president—were going over his head. HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_021138

Page 20 - HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_021139

ay MICHAEL WOLFE the end of the year, Trump was casually mocking his chief of staff and his penchant for efficiency and strict procedures. Indeed, both men were openly trashing each other, quite unmindful of the large audience for their slurs. For Trump, Kelly was a “twitcher” and “feeble” and ready to “stroke out.” For Kelly, Trump was “deranged” and “mad” and “stupid” The drama just got weirder. In February, Kelly, a retired four-star general, grabbed Trump adviser Corey Lewandowski outside the Oval Office and pushed him up against a wall. “Don’t look him in the eye” whispered Trump about Kelly after the incident, circling his finger next to his head in the crazy sign. The con- frontation left everybody shaken, with Trump asking Lewandowski not to tell anyone, and Lewandowski, when talking to the people he did tell, saying that he had almost wet himself. By March, Trump and Kelly were hardly speaking. Trump ignored him; Kelly sulked. Or Trump would drop pointed hints that Kelly should resign, and Kelly would ignore him. Everyone assumed the countdown had begun. Various Republicans, from Ryan to McConnell to their right-wing adversary Mark Meadows, along with Bannon, had gotten behind a plan to push House majority leader Kevin McCarthy for chief of staff. Even Meadows, who hated McCarthy, was all for it. Here finally was a strat- egy: McCarthy, a top tactician, would refocus an unfocused White House on one mission—the midterms. Every tweet, every speech, every action would be directed toward salvaging the Republican majority. Alas, Trump didn’t want a chief of staff who would focus him. Trump, it was clear, didn’t want a chief of staff who would tell him anything. Trump did not want a White House that ran by any method other than to satisfy his desires. Someone happened to mention that John E Kennedy didn’t have a chief of staff, and now Trump regularly repeated this presi- dential factoid. +e The Mueller team, as it pursued the Russia investigation, continued to bump up against Trump’s unholy financial history, exactly the rabbit hole SIEGE 31 Trump had warned them not to go down. Mueller, careful to protect mt own flank, took pains to reassure the president's lawyers that he wasn’t pursuing the president's business interests; at the same time, he was pase ing the evidence his investigation had gathered about Trump’s business and personal affairs to other federal prosecutors. . On April 9, the FBI, on instructions from federal prosecutors in New York, raided the home and office of Michael Cohen, as well as a room he was using in the Regency Hotel on Park Avenue. Cohen, who billed him- self as Trump’s personal lawyer, sat handcuffed for hours in his kitchen while the FBI conducted its search, itemizing and hauling away every electronic device its agents could find, Bannon, coincidentally, also stayed at the Regency on his frequent trips to New York, and he would sometimes bump into Cohen in the hotel’s lobby. Bannon had known Cohen during the campaign, and the lawyer's mysterious involvement in campaign issues often worried him. Now, in Washington, seeing the Cohen news, Bannon knew that another crucial domino had fallen. “While we don’t know where the end is,” said Bannon, “we can guess where it might begin: with Brother Cohen” + On April 11, three weeks after the president signed the budget bill, Paul Ryan—one of the government's most powerful figures given the red lican lock on Washington—announced his plan to leave the Speakership and depart Congress. “Listen to what Paul Ryan is saying,” said Bannon, sitting at his table in the Embassy early that morning. “It’s over. Done. Done. And Paul Ryan wants the fuck off the Trump train today:” Ryan had been telling almost anyone who would listen that as id as fifty or sixty House seats would be lost seven months hence in the mid- term elections. A Ryan lieutenant, Steve Stivers, chairman of the National Republican Congressional Committee, was estimating a loss of ninety to one hundred seats. At this gloomy hour, it seemed more than possible that the Democrats would eliminate their twenty-three-seat deficit and HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_021139

Page 21 - HOUSE_OVERSIGHT_021140